Romans 13 is an often cited passage when Christians think about faith and politics. The very first verse of the chapter reads:

Let every person be subject to the governing authorities. For there is no authority except from God, and those that exist have been instituted by God (Romans 13:1, ESV).

As St. Paul argues in his epistle to the Roman church, whoever disobeys these authorities disobeys God. Government is intended to encourage the doing of good and punish those who do wrong.

This passage engendered much discussion over the millennia since it was penned. What does it mean to be “subject”to governing authorities? Is there a line to be drawn when one should not obey governing authorities? After all, before Paul’s conversion, Peter and the apostles declared, “We must obey God rather than men” (Acts 5:29).

These are important questions. In this article, we take on the first question. What it means to be subject to the magistrates of this world? But our interest is more in the deeper orientation towards such subjection. In other words, what is our posture towards government supposed to be? Are Christians to be boot-lickers? Are we friends of earthly authority?

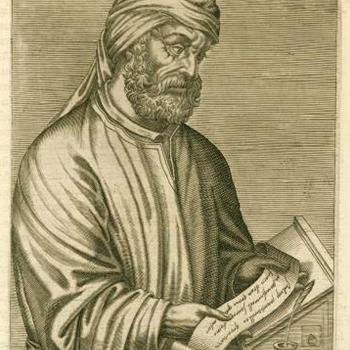

To answer this question, we examine a rather early saint in the Christian tradition: St. Polycarp. Polycarp was one of the first martyrs of the Christian faith, executed by the Roman empire. He was not only an exemplary witness to the truth. He is an embodiment of Romans 13:1.

Christians the Imperial Cult

The Martyrdom of Polycarp is an old story. We do not know who wrote this ancient text. Nor are we certain of when it was originally penned, although some suggest it was written in 186 CE.

The unknown author situates Polycarp’s story in a time when Christians were under persecution. Much of Rome’s persecution against the Church in Christianity’s early centuries was irreducibly political. The Pax Romana (Roman peace) was sustained by degrees of religious tolerance. People groups in Rome were free to believe in and worship their own gods. But this tolerance had limits. Rome’s first emperor, Caesar Augustus, instituted what we now call the Roman imperial cult.

Not all emperors declared themselves living gods or deities. But nevertheless, Roman emperors were to be venerated in a religious way, deriving their authority and legitimacy from the gods. Honoring the emperor was therefore one and the same with wishing prosperity and success for the empire. Conversely, non-participation in this imperial cult was subversive and dangerous to the fabric of the empire itself.

The early Christians refused to offer sacrifices to the emperor. They refused to acknowledge emperors in this way. Nor would they swear by the emperor’s fortune (which will become important later). It is against this religio-political background that the story of Polycarp takes place.

The Story of Polycarp

Polycarp was himself an elderly man. In the story, he says that he had been following Christ for over eighty years! He was fiercely devoted to the faith, and was an important leader in the Church for many.

Before the mob sought out Polycarp, they had already been persecuting many other Christians. These people died gruesome deaths (which we will not recount here). Some, like one Quintus, caved in and offered incense to the emperor to avoid death.

The crowd began to call for the death of Polycarp. Though Polycarp was initially willing to respond to their call, most of his fellow believers urged him to retreat. And so he did. He fled from farm to farm, taking refuge with other Christians.

His pursuers caught and tortured two slaves who worked one of the farms that Polycarp had hid in. One of them broke under pressure and revealed Polycarp’s location. Finally, they caught up with him. Polycarp could have fled once more, but chose not to. Polycarp invited them into the house he was staying in and had them served with food and drink. His pursuers were shocked that the mob had called for the death of such an old man.

Five Chances to Avoid Death

Finally, his pursuers brought him back into the city. Here, we see Polycarp’s interaction with an unnamed proconsul, one whom Paul would call a governing authority. The proconsul gives Polycarp five opportunities to deny Christ. But each time, Polycarp refuses.

The first time, the proconsul says,

“Swear by the fortune of Cæsar; repent, and say, Away with the Atheists.”

At the time, Christians were accused of being atheists. Not because they did not believe in a god. But because they did not worship any Roman gods, nor did they venerate the Roman emperor. Polycarp flips this offer on its head, pointing to the unbelieving crowd and saying, “Away with the Atheists.”

The second time, the proconsul says,

“Swear, and I will set you at liberty, reproach Christ.”

But to this, Polycarp responds that of the eighty-six years he served Christ, Christ “never did me any injury: how then can I blaspheme my King and my Saviour?”

The proconsul offers Polycarp a third chance, to swear by Caesar’s fortune, to which Polycarp responds simply by saying, “I am a Christian.” Swearing by Caesar’s fortune, as we will see, was an act associated with the Roman imperial cult.

Then, the proconsul commands Polycarp to explain himself to the mob. But to this, Polycarp says,

To you I have thought it right to offer an account [of my faith]; for we are taught to give all due honour (which entails no injury upon ourselves) to the powers and authorities which are ordained of God. But as for these [the crowd], I do not deem them worthy of receiving any account from me.

In the fourth and fifth chances, the proconsul grows evidently impatient, and threatens to set wild beasts on the Christian or burn him. But neither threat phases Polycarp. He is summarily executed by the empire.

Polycarp and the Powers

I want to examine the third chance that Polycarp was given, because there we see Polycarp articulate the Christian posture towards worldly powers. Just like Pontius Pilate thought about Christ, the proconsul thought he had the power of life and death over Polycarp. But like Jesus about Pilate, Polycarp knew where the proconsul’s power came from.

When the proconsul tells Polycarp to swear by the fortune of Caesar, Polycarp knows that to be Christian is to not swear by the fortune of any worldly ruler. To swear by an emperor’s fortune (or “genius” or “daemon”) was to acknowledge that the emperor’s power was self-derived and therefore unsuperceded. It was also to acknowledge to some extent an emperor’s divine status. This runs contrary to the Christian view that earthly power comes from God, not man.

It is the temptation of all worldly rulers to believe that their power is truly theirs. And that they have no one to answer to for how they wield their power. Therefore, Polycarp shows us that being subject to the governing authorities entails reminding them that we are Christians. As long as there are Christians, worldly rulers must be reminded that their power is not ultimately theirs.

Polycarp’s Posture to the Magistrates

The second lesson we learn is when the proconsul tells Polycarp to explain himself to the people. Polycarp responds that the mob does not deserve an explanation. It is right, however, for the proconsul to be told about Polycarp’s faith. Not because the proconsul deserves an explanation. But because it is the merciful thing for Polycarp to do: to tell the proconsul that his power is relative and comes from elsewhere than himself.

This is a great reversal indeed. For it is the proconsul who believes that he is being merciful to Polycarp. As Polycarp explains, Christians are taught to honor earthly authorities, barring any injury this may incur upon a believer. Even here, it is strange that Polycarp nevertheless grants honor to the proconsul when he is about to face death. This is the principle found in Romans 13:1.

But Polycarp’s granting of honor does not come from a place of groveling before the powers of the world. It does not come in the form of capitulation. It comes instead from the declaration of what is true: Your power, Caesar, comes from God. And it is not you who is being merciful to me, but I who am being merciful to thee.

The Meaning of Romans 13

The truly Christian conception of power is a subversive one. It takes the worldly understanding of influence and turns it on its head. In many ways, this account of Polycarp mirrors Christ’s trial before Pilate, where we get a very similar critique of worldly rulers.

What is important for us here is what it means to honor and be subject to governing authorities. Romans 13:1 gets bandied about quite often. In 2020, it was quoted to support the COVID-19 gathering restrictions on religious services. And in 2025, it is cited to support the legislation of dehumanizing immigration policies.

Both of these issues I believe have not to do with Romans 13:1, but with Genesis 1:27. This is the verse that says that male and female are created in the image of God. And all image bearers have equal dignity; dignity which must be upheld in terms of health and seeking refuge or a better life.

In terms of Polycarp before the proconsul (and Christ before Pilate), Romans 13:1 is not intended for winning partisan points. It is instead an assertion as much as it is a subjection to worldly rulers: your power is not your own, and for as long as the Church lives, you shall know this.

Postscript

The more prevalent interpretation of Romans 13:1 does not conflict with the interpretation advanced here. In fact, they complement each other. Most situate Romans 13:1 in the context of Paul’s deeds as recounted in Acts. The authorities prohibited Paul from preaching the Gospel. But because obedience to God supersedes obedience to men, Paul acted out in civil disobedience. He continued to preach, but also accepted the punishments that the magistrates meted out for doing so.

Unlike Polycarp, Paul did not tell the magistrates that their power was relative. He showed them by mercifully subjecting himself to their punishments as he obeyed the higher law of God.