The narrative of decline has a strong hold on American Christians, particularly Protestants. The narrative goes like this. For decades, Christianity has been on the decline in the US. This steady decline indicates that America has given into nihilism, relativism, and has entered an era of post-Christianity. In Nietzschean fashion, believers themselves declare the death of God in American society.

I want to argue that this narrative is untrue. Christianity is not declining any longer, nor has it declined enough to declare that America is a post-Christian country. But past this argument, I believe that the cogency of this narrative, or the force of its appeal, stems from a confused conception of power among American Christians, especially American evangelicals.

A Declining Christianity: Important Moments

I have recently taken an interest to how high-profile data informs public discourse. The narrative of decline derives its prevalence and persuasiveness by the amount of headlines, Christian and secular, insisting that Christianity is on the decline. These headlines often draw on findings from high-profile research centers like Pew and Gallup.

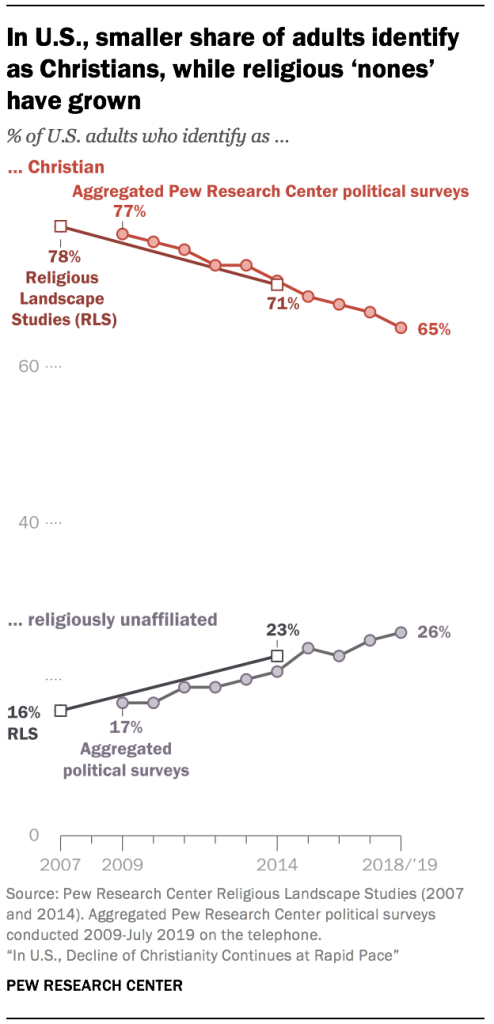

In October 2019, Pew published a report titled, “In U.S., Decline of Christianity Continues at Rapid Pace.” In the report, Pew found that America’s Christians had fallen to 65%, while the “nones” or religiously unaffiliated had risen to 26%. This was a significant change from only a decade ago, when Christians constituted 77% of the population and the nones 17%.

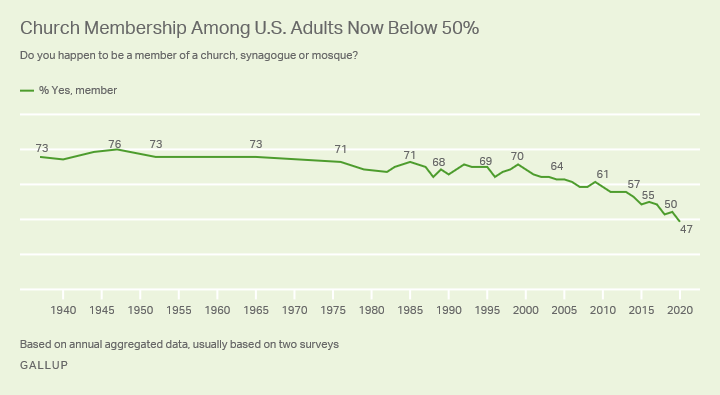

Then, in 2021, Jeffrey M. Jones with Gallup published an article titled, “U.S. Church Membership Falls Below Majority for First Time.” Jones showed that according to Gallup’s long history of polling stretching back 1937, church membership (which encompasses more than just Christians) had declined from 73% to 47% of the population.

Like Pew’s 2019 report, Jones proposed the rise of religious disaffiliation as a possible explanation for this decline. Both of these reports and more were followed with journalists and scholars heralding the decline and eventual fall of American Christianity. Many often saturated these findings with their own narratives of religious decline. Certain of these commentators were Christians themselves. But before examining these voices, we need to acknowledge that the decline has stopped.

The Decline has Stopped

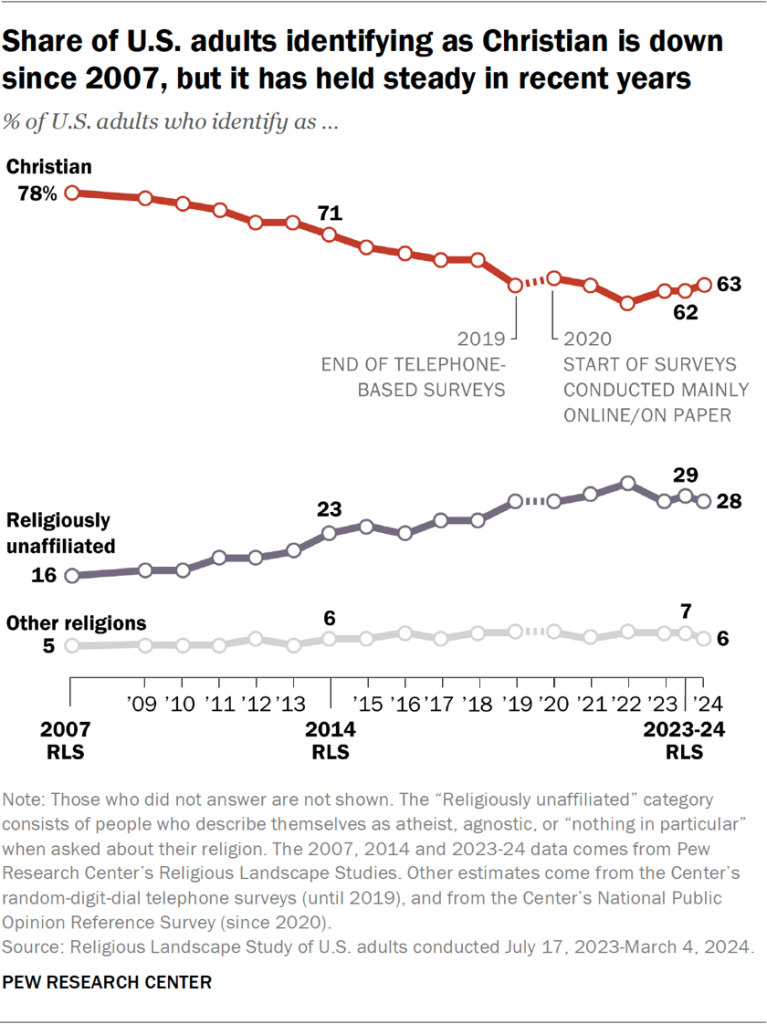

Late last month, Pew released yet another report entitled “Decline of Christianity in the U.S. Has Slowed, May Have Leveled Off.”

After decades of consistent decline, the trend has relatively stabilized since 2020, for the most part remaining in the lower 60%. Furthermore, Christianity itself remains the majority religion in the US. Calling America “post-Christian,” or at least claiming it is still on the decline, must be vigorously scrutinized.

The Nietzschean announcement of the death of God in America is unfounded, whether it is made by Christians or non-Christians. Yet, there remain Christian voices that insist on this death. We now turn to a careful consideration of these voices.

Decline and Hegemony

Rod Dreher, author of The Benedict Option, exemplifies two forms of the American Christian decline narrative. Writing for The European Conservative, Dreher insists that, “The American people are, in fact, post-Christian.” For Dreher, this is not just a demographic fact. It is also a political one.

Dreher laments that on “abortion, sexual orientation and gender identity, euthanasia, and related issues, the American people have abandoned bedrock Christian teaching, and have endorsed laissez-faire libertarianism.” Yet it is this very same libertarianism grounded in advocating for religious freedom that American Christianity can “survive” through seeking religious liberty protections. (Note that a post-Christian world is one in which Christianity cannot simply exist, but must “survive” in.)

For those like Dreher, America has lost its golden age of Christian influence. At best, Christians can only work to gain legal protections from an antagonistic world.

Others, however, view a post-Christian America as a source for “boldness” in Christian witness, like Samuel James writing for The Gospel Coalition. And in a different article, Dreher believes the Church must take a heroic last stand like the Christians “who stayed behind under Communism [and] emphasized the radical importance of being able and willing to suffer for the faith.”

Decline for this second stream of Christians is not merely numerical. It is cultural and political. Either the believer pessimistically seeks to carve out niches for Christians to exist in. Or one must become a martyr. Both responses assume a world ready to pounce on once hegemonic Christians.

The Logics of Declinism

The narrative of decline is not exclusive to mostly white American Christians like Dreher and James (Christians of color have already been a minority for most of American history and so perceive no fall from hegemony). This narrative actually has a name: declinism. Writing for Psychology Today, Eva M. Krockow defines declinism as

a pessimistic thinking bias, which leads people to believe that things are constantly getting worse over time. The bias reflects an overly negative view of the current situation, and it usually goes hand in hand with tendencies to romanticize the past.

But declinism does not often end in a quietist, inactive pessimism. It is often employed to shore up new political programs. Krockow writes, “By describing the present situation as a downward spiral of misery, politicians often try to convince the public that a change in leadership is long overdue.” One thinks in particular of the Make America Great Again movement. MAGA is a movement which bases itself on nostalgic memories of America’s great past, corrupted by woke elites, immigrants, and progressive bureaucrats.

I do not seek to make a partisan point, here. I do not believe that “post-Christian” or decline narratives explain Christian support for Trump. In fact, that is not the present concern. The concern is rather how Christians conceive power and dominance more broadly in relation to a perceived decline.

Moving Past Declinism

The main question I wish to pose for other American Christians is this: if Christianity is not on the decline, and if America is not post-Christian, what are we to do? Can we conceive of Christian witness without needing an amnesiac nostalgia of the days of Christian hegemony? Can we acknowledge that we are still predominant in a country that is not on the whole anti-Christian precisely because most of the country is Christian?

I do not think American Christians know what to do with predominance. The persecution complex inevitably leads believers to think that the world is out to get them. The narrative of decline offers Christians a way to cope with this felt victimization. But it also enables Christians to excuse themselves of the power and responsibility (and majority status) that they already possess and are unlikely to lose in the future.

In the current environment of American Christianity, declinism motivates streams of Christians towards three directions:

- Taking America back for God and restoring Christian hegemony (which the latter part already exists).

- Removing oneself from the world to avoid the alleged onslaughts of persecution and forming an alternative Christian subculture (which American evangelicals have already done).

- Or, fantasizing about how minority status will finally achieve religious authenticity in a complacent American Church.

I am satisfied with none of these routes. And I do not think any reader should be, either. We are still the majority. And the country is not out to get us. We are complacent, and declinism with its promises of boldness, revival, and authenticity is not coming to save us.

De-Dramatizing Status

We must do without grand narratives of decline and post-Christianity. These narratives certainly have their appeal. They dramatize our status in the world, and make stakes seem high. They make us seem the victims or the heroes. Either way, these narratives insist that we must be on the decline to get anything done. But we can excuse ourselves from our predominance no longer.

Wanjiru Gitau wrote an excellent study on megachurch Christianity in Nairobi, Kenya. There is a passage in her book where she writes about the very thing American Christians are in need of: an ethical vision of success. Without such a vision, Christians will always see success as something that must always be idealized in a nostalgic past. Or we will see success as inherently perverting, against which only a return to the early Church’s minority status can save us.

Gitau notices a

nervous nail biting among Christians wherever socioeconomic success has emerged as shared societal reality. Christians are edgy both about the need to help the poor and about the focus on creating and living with wealth. . . . [T]he way forward is neither the ascetic denunciation of success nor an uncritical embrace of all the wealth and success one can get. . . . What is needed is an ethical vision of success. [1]

American Christians must cease relying on dramatizations to excuse themselves of their cultural and numerical success. We need what Gitau calls “a consistently developed theology of how to be Christianly prosperous.” [2] We lack this theology of prosperousness in both the prosperity gospel, with its own dramatizing narratives of how God wants believers to be wealthy, and the decline narratives, which cannot bear the thought of success in the present.

Conclusion

I have made the case against narratives of decline. And I have pointed out their underlying flaws. American Christians, with the exception of those who refuse to wring their hands in declinist despair, are unforgivably complacent. And holding to declinism only reinforces complacency as believers await the chance to make a heroic last stand like Dreher’s Christian dissidents under communism.

American Christians do have power and influence in America. The decline has stopped. America is not post-Christian. What American Christians need to think about is how to be authentic in following Christ with such power and influence.

Building a just common life with one’s civic neighbors does not happen by recusing oneself of responsibility. Especially when one’s tradition has been made to justify the oppression and marginalization so many of one’s neighbors. The flaw of declinism is that it lies about Christianity’s status in the US and simultaneously blames those whom American Christendom has marginalized and dispossessed for Christianity’s supposed decline.

This is not the way. The American Church must contend with righting the wrongs of the past in the present, not wallowing in idyllic nostalgia. American Christians must accept that the vast majority of their civic neighbors, though there exist deep-seated disagreements, are not out to de-platform or dismantle Christianity. We must accept that the task of Christian witness in America is much less dramatized than declinists would want us to believe. And it is more drawn out than we are comfortable with. The work of Christ is not often grandiose, but happens in the mundane and ordinary.

References

1. Wanjiru M. Gitau, Megachurch Christianity Reconsidered: Millennials and Social Change in African Perspective (Downers Grove, IL: IVP Academic, 2018), 151.

2. Gitau, Megachurch Christianity Reconsidered, 151.