There is a growing trend in American religion: women are leaving organized religion. According to data analysts, this trend is quite new. Some point to 2016 or 2018 as its starting point.

Given that today is International Women’s Day, I thought it proper to open up the conversation on gender and religion. The data published on this topic has generated massive amounts of discussion. And commentators have offered a variety of explanations for why this trend is happening.

Traditionally, women used to be more involved in religion than men, especially among Christians. Now, especially when we compare younger cohorts, young women have become less and less religious, even on the same level as young men.

We will take a look at these gender dynamics in prior times, surveying explanations of why women used to be (and in many parts of the world, still are) more religious than men. Then, we will try to account for why this has changed in America today. We link this conversation to broader concerns about how certain strands of American Christianity are becoming more politically homogenous.

Women More Religious Than Men?

For decades, scholars studying religion have found that women rank higher on religiosity than men. Some traditional measures of religiosity include the number of religious beliefs a person holds, the frequency of religious service attendance, and the frequency one engages in other religious practices like prayer.

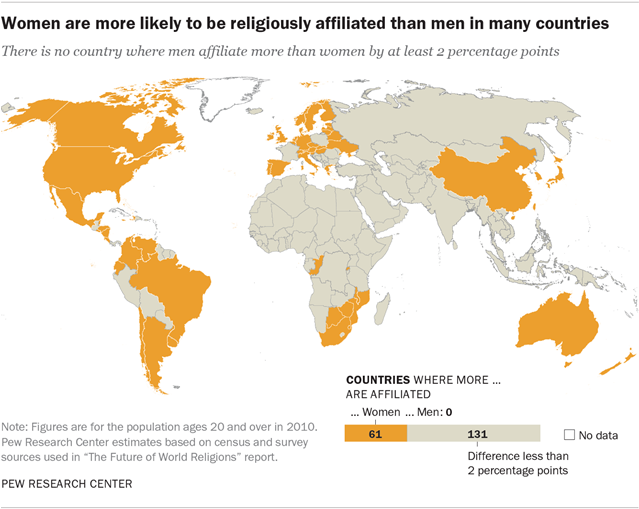

Consistently, commentators and scholars writing on women and religion cite Pew Research Center’s report released in 2016. In the report, titled “The Gender Gap in Religion Around the World,” Pew takes a global look at gender and religiosity. There were many countries in which men participated more in religion than women. But in countries like the United States, women led in measures of religiosity.

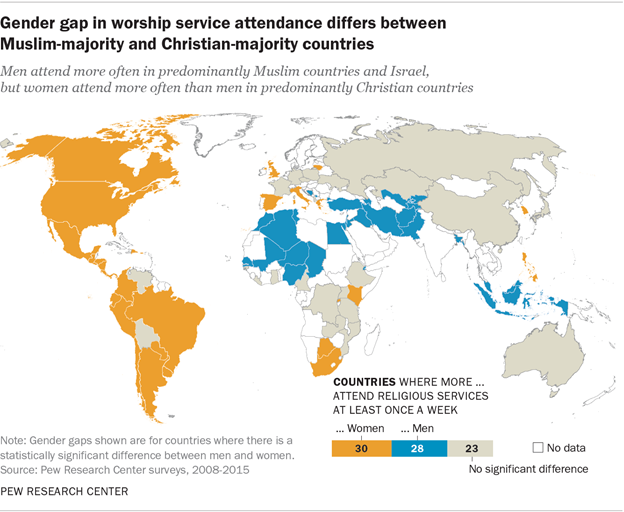

Another interesting insight from this report is that in Muslim-majority countries, men attend religious services more frequently than women. But in Christian-majority countries like the US, women attend more frequently than men.

Scholars have known about this so-called religious “gender gap” since the 1930s. As Pew points out, it wasn’t until the 1980s when scholars tried to understand why this gap existed.

As we said above, things have changed. To better understand the current state of American religion, we should better understand why American women used to be more religious than men.

Explaining the Gender Gap

There are a number of explanations offered for why women tended to be more religious than men globally. Some scholars like sociologist Rodney Stark suggested that women were biologically predisposed to be more religious than men. According to Stark, women are less willing to take risks than men. Regarding religion, women would be less willing to risk punishment in the afterlife for breaking religious norms than men. Hence, women are more religious than men.

In 1991, Edward H. Thompson Jr. found that rather than gendered self-perceptions rather than gender itself could explain the gender gap. In his psychological test of American undergraduate students, Thompson found that participants who understood themselves to be more stereotypically feminine were more religious than other participants. And understanding oneself to be feminine was a stronger determinant of religiosity than actually being female.

These studies, I believe, seem too essentialist to account for state of American religion as we see it today. If it is in the nature of women to be more religious than men, what about when women become as less religious as men are?

Pew offers more explanations which are more helpful in this respect. Marta Trzebiatowska and Steve Bruce deploy a secularization framework to explaining the gender gap. Secularization theory, broadly put, predicts that as societies progress scientifically and technologically, religion will either disappear or privatize (that is, be kept to oneself, outside the public sphere). This theory has been widely rejected by social scientists and religious studies scholars. Societal progress does not diminish religion. In fact, sometimes it strengthens it. However, Trzebiatowska and Bruce still offer an interesting explanation.

For Trzebiatowska and Bruce, men were secularized by the industrial revolution before women were. Men worked in diverse environments that made their faith voluntary, rather than unquestioned and natural. Women at the time remained relegated to domestic life in the home. Thus, women would be exposed to pluralism and modernization later than men, and lag behind in becoming less religious. This explanation is more open-ended, allowing us to think about gender dynamics today.

Many of these more open-ended explanations focus much on how women in the workplace are less religious than women who stay at home. David de Vaus and Ian McAllister argue that work offers benefits that one would otherwise receive in religious community. Other scholars argue that work affords women security that they would have otherwise needed from religious communities.

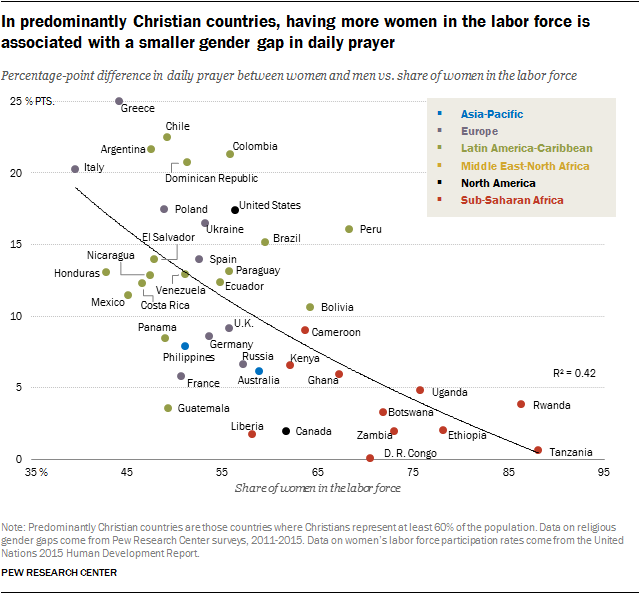

Interestingly, Pew finds that having more working women in predominantly Christian countries corresponds to more similar, lower levels of religiosity amongst men and women. But in countries not predominantly Christian, the trend does not always stay the same.

Closing the Gender Gap

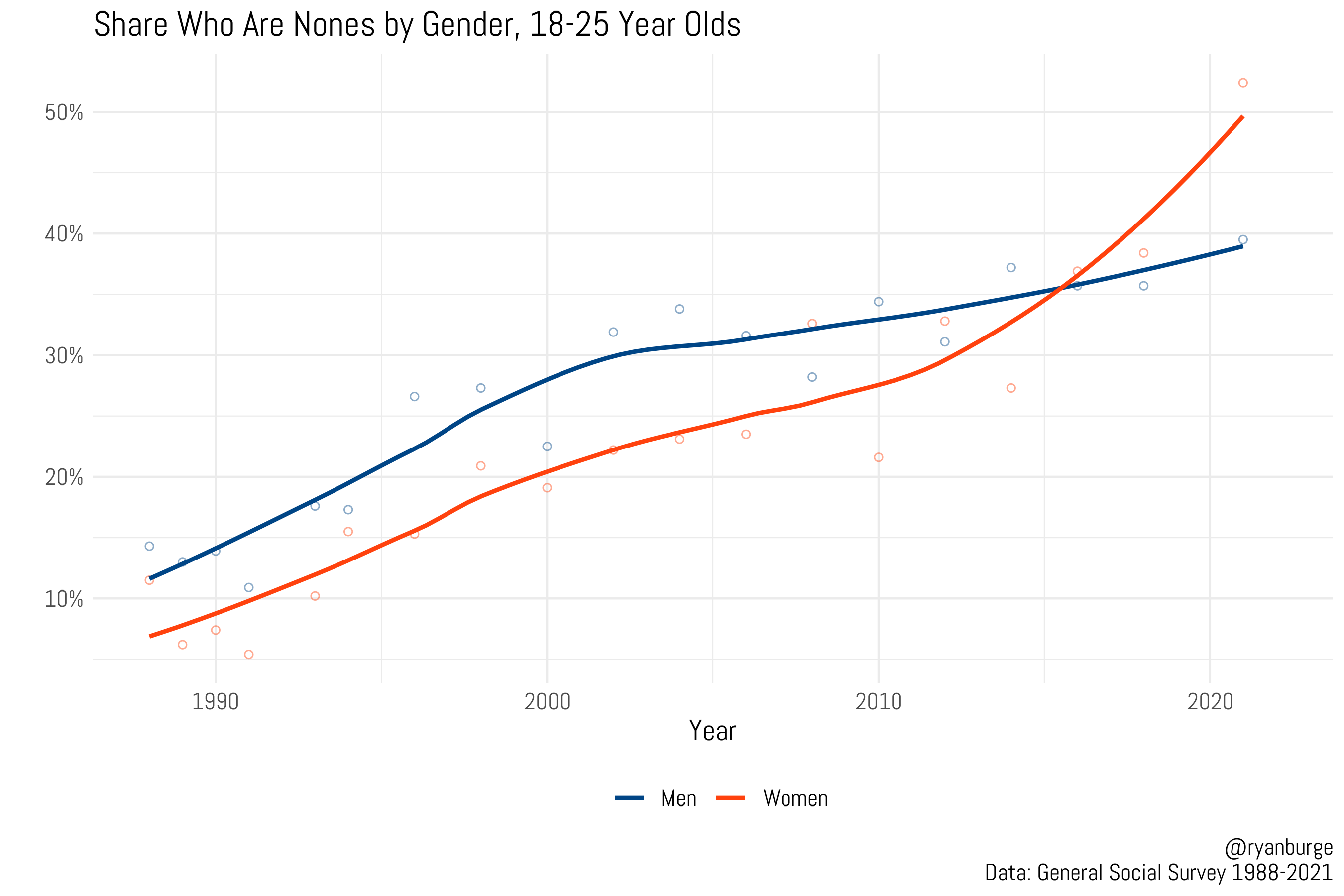

Now, we fast forward to today. The gender gap between American women (who used to be more religious) and men (who have tended to be less religious) has diminished. In some generational cohorts, the gap has even reversed. Social scientist and pastor Ryan Burge has pointed out that this trend is not only found in one data set. It is found in three: the General Social Survey (GSS), the Survey Center on American Life, and the Cooperative Election Study (CES).

Let’s take a look at those graphs. In the GSS, we find that leading up to 2016, the gender gap between men and women was starting to close. Then, around 2015 or 2016, the gender gap actually reversed and continued to grow in the opposite direction. Women were not only as likely as men to be religiously unaffiliated; they were even more so.

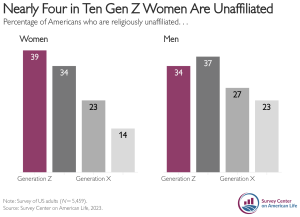

Now, let’s take a look at the data from the Survey Center on American Life. This graphic focuses mostly on younger generational cohorts. But from here, we see that Gen Z women are more likely than Gen Z men to be religiously unaffiliated.

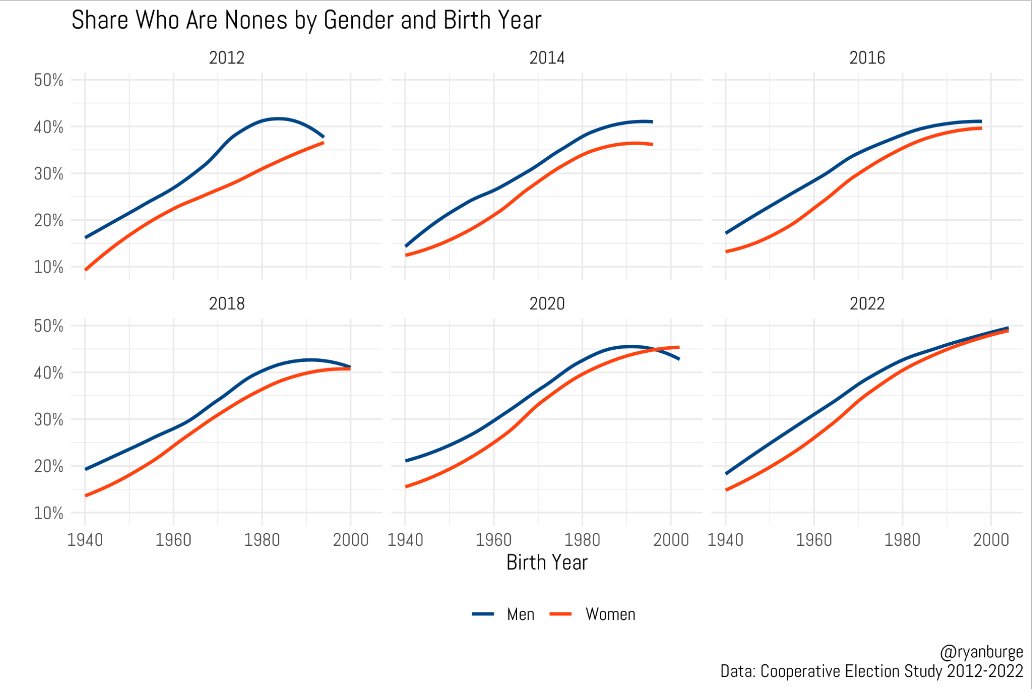

Lastly, Burge created a graphic based on the CES data. These graphs depict how many men and women are religiously unaffiliated by birth year. As we can see, the distance between the two lines grows smaller with each year, especially among younger people. In 2020, we saw young women outpace young men in religious unaffiliation. In other years, young men and women are virtually just as likely to be unaffiliated.

Re-Explaining the Gender Gap

We know that the old gender gap in American religion, in which women were more religious than men, was a contingent, not a necessary, reality. As mentioned above, explanations of the old gender gap that essentialized men and women (essentially saying that women are more religious by nature) do not hold much purchase today.

The more open-ended explanations, which explained the old gender gap as a product of society, seem more appealing. It is therefore our task to search for an open-ended explanation of the new gender gap. This new gender gap is one in which men and women are at least equally low in religiosity. At most, the new gender gap is one in which women are now less religious, even compared to men.

There have been a number of explanations floating around in the discourse. The Survey Center on American Life suggests that younger women are increasingly holding to social views that conflict with traditional religious norms. Younger women are more likely than older cohorts and their male counterparts to identify as feminist, say that churches treat men and women unequally, and believe that abortion is a reproductive right (Burge agrees that abortion is part of the explanation).

Melissa Deckman writing for Religion News Service, drawing on yet another dataset (PRRI) adds that young women are increasingly less likely to say religion is the most important thing in their life. These Americans are also not likely to believe that “women [should] stay home, raise children and remain subservient to their husbands.”

Social Sorting: The Broader Issue

To close, I wish to link this conversation with a broader concern facing American Christians in particular: social sorting. Lilliana Mason published a brilliant academic article in 2018 titled “Losing Common Ground: Social Sorting and Polarization.” As Mason points out, diversity within opposing groups, or cross-cutting identities, have long been tied to the “great stability of American democracy.” [1]

In other words, a diverse society is possible when its people have overlapping and conflicting allegiances across class, race, gender, and so on. When this cross-cutting diminishes, people become more intolerant of outgroups, and society risks destabilization.

This is concerning. Democrats and Republicans are becoming more ideologically distinct. But even worse, now one can often tell a person’s party by their choice of vehicle or the grocery store they shop at. [2] As party groups become more internally homogenous, they can become more intolerant of outgroups. In-group simplicity is the enemy of social diversity, one could say.

Significant streams of American Christianity, it seems, are undergoing this homogenization. Michael Emerson wrote a piece recently in The Conversation. Emerson points out that in past years, one could account for political differences between Christians based on denominational lines. Evangelicals and mainline Protestants, for example, exhibited very different political outlooks.

Now, denominational differences are shrinking. Political differences are better explained by Emerson’s concept of the practicing Christian: “people who say that they are Christian, that their faith is very important to them, and that they attend church at least monthly.”

White Christians, whether they are evangelical, mainline, or Catholic, tend to have similar views if they are practicing Christians. One finds the same pattern among Asian American Christians. We do not yet know if this trend is happening among Hispanic Christians, though these Americans are not voting as strongly Democrat like they used to. The exceptions to this trend are African American Christians. These Christians vote majority Democrat, practicing or not.

What Emerson leaves unsaid is that congregations seem to be experiencing what Mason calls self-sorting. Given the data, we can conclude that Christians who are not Republican and do not support Trump are leaving congregations which have normalized being those things. The exit of these believers from conservative churches renders them illegible under Emerson’s “practicing Christian” concept, precisely because they are no longer attending church. In other words, practicing Christians in white, Asian American, and possibly Hispanic congregations are becoming more politically alike because political dissidents are leaving.

If this is true, significant streams of American Christianity are losing the cross-cutting identities so important to toleration and democratic stability. Young women leaving organized Christianity, if they are doing so for political reasons, is but one symptom of this broader phenomenon. Time will tell if this explanation is correct.

References

1. Lilliana Mason, “Losing Common Ground: Social Sorting and Polarization,” The Forum 16, no. 1 (2018): 47.

2. Mason, “Losing Common Ground,” 48-49.