As director of The Great Gatsby, Baz Luhrmann made a controversial choice in choosing to depict the parties of the Roaring Twenties with music featuring today’s top artists and styles. In one sense, this made the movie a less “true” depiction of what life during the Jazz Age was life. The minor allusions to that era, the droning trumpets and hints of blues, are authentic twenties, but the rap styling and rapid beats would have been foreign to those alive during that era. Yet in another sense, Luhrmann’s decision better conveyed to our modern ears the sense of excitement and vibrance that roaring parties offered at the time.

Jazz sounds quaint and old-fashioned to us, but at the time, it was provocative and dramatic. Conservative commentators at the time anxiously questioned the value of jazz. If one is trying to convey a scintillating, rambunctious party to a modern audience, jazz music won’t do it. To communicate the heart of the jazz age to a modern ear requires, in a way, abandoning literal authenticity. This permits Baz Luhrmannt to actually convey a deeper truth – to pass along the spirit of things.

A literalist will question the value of this technique—insisting perhaps on a stricter limitation on truth—but would fail to appreciate the full value of art. Picasso once said, “We all know that Art is not truth. Art is a lie that makes us realize truth at least the truth that is given us to understand.” Sometimes figurative language conveys the spirit of things better than literal truth does.

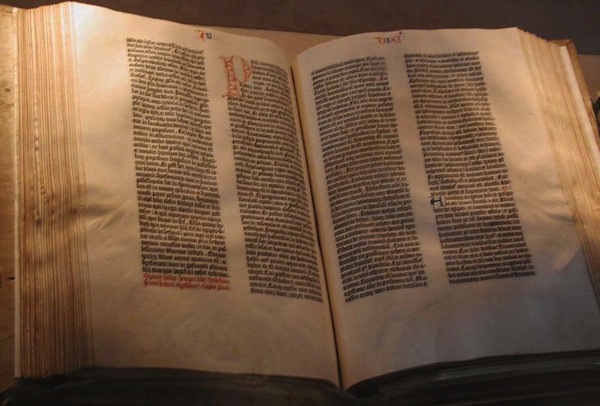

Nowhere is this more clear than in the scriptures. The Bible is a winding, miraculous work of art—composed of a variety of books by different authors at different times, spanning genres from history to poetry to epistle to prophesy—rather than a scientific or logical textbook. Written to a particular audience at a particular time, its commandments may often seem jarring to modern ears. Yet just as Luhrmann offers a spirit of truth in his musical choices for The Great Gatsby, so God has a keen ear to communicate the spirit of truth through the scripture.

To my feminist ear, commands such as “wives, obey your husbands” smacks of patriarchy. But those in Ephesus would have been more shocked by the radical equality and sacrifice conveyed by, “Husbands, love your wives, just as Christ loved the church and gave himself up for her.” I will always be deeply wounded when I read Deuteronomy 22:28-29 and see that Moses has commanded for rapists to marry their rape victims. Yet I also know at a time when virginity is associated with a bride’s value and women have limited economic opportunities, the alternative would have significantly jeopardized a woman’s financial security and thus her life itself. The spirit of truth here may be concern and protection for the victimized, even if the facts involved sounds like brutality to me.

When we conceive of the scripture as a work of art, we see that God may be conveying the spirit of the matter in a particular time and particular place. Sometimes conveying this truth may require language or involve commands that makes modern readers uncomfortable. But it’s our role as intelligent readers to discern what is truly being said. Flannery O’Connor once wrote, “art never responds to the wish to make it democratic; it is not for everybody; it is only for those who are willing to undergo the effort needed to understand it.” I suspect the same is true for Scripture.

[Image of the Gutenberg Bible from Wikipedia]