In his book Word and Church Anglican theologian John Webster writes, “At its best… attention to ‘context’ can remind theology that there is no pure language of Zion, and that theology’s conceptual equipment is borrowed from elsewhere. But at its worst it is a form of mental and spiritual laziness, an unwillingness to admit that theology must go about its own business if it is to speak prophetically and compassionately about the gospel to its neighbors.”

In other words, when theology ceases to be a distinctive discipline (and when the church ceases to be a distinctive community), it ceases to be of any restorative value to the world. At a time when both Catholics and evangelicals are reconsidering their approach to adult outreach, Catholics doing so under the New Evangelization and evangelicals doing the same in the name of being “missional,” Webster’s words are essential.

Recently, both Catholics and evangelicals alike have noticed the rise of the “nones,” and the many social and cultural realities such a rise implies. This has led to a veritable deluge of new books written to address this problem in one way or another—everything from George Weigel’s call for an “evangelical Catholicism,” to the “missional” theology of Ed Stetzer to more moderate voices like Redeemer Presbyterian’s Tim Keller, who has managed to connect with adults exceptionally well while his church retains many traditional liturgical staples.

One of the emerging trends resulting from this new interest in adult outreach is holding church services in unconventional places. NPR has reported on evangelical and mainline Protestant congregations meeting in pubs and a Patheos blogger named Lisa Hendey wrote about her experience attending Mass in a nearby mall. My own denomination has a few ordained pastors who preside over worship services at truck stops. On a recent trip I even heard an announcement in Midway Airport for a worship service. The idea seems to be that if we’re going to go into the world, that means taking the liturgy with us wherever we go. Quote Hendey: “While Mass in the mall may sound a bit odd, isn’t this really the New Evangelization at its finest — finding people right where they are and bringing the Word to them?” In the name of “outreach,” we’ve moved very easily—and without much attention—to reimagining the role and place of the liturgy. Another way of putting it: perhaps that in the name of outreach we have come to think of the liturgy as being something merely incidental to spiritual formation, that the liturgy is an infinitely flexible form that can be taken and used anywhere.

But there are some significant problems with this approach. First, if we focus too myopically on the question of outreach, we run the risk, as Webster points out, of compromising the very subject and reason for our outreach. (We aren’t that far removed from the vacuous church growth movement, after all.) If we adopt the models, structures, and locations of our liturgy to new environments, we run the risk of our message being conditioned and limited by the language and concepts of those environments. By the time a non-Christian hears our message, that message may have become so watered down that there will be nothing left to tell them.

More pointedly, can we cultivate Christian understandings of wealth while worshipping in a mall? Perhaps more distressing still is the possibility that the Christian community simply becomes one more public group meeting at the mall (a possibility Hendey seems to find desirable), a more religious version of the senior citizens doing laps on weekday mornings, or one more social group that meets at the pub throughout the week. Viewed this way, the dominant social institution is no longer the church itself, but the community implied by the venue in which the church is meeting—the mall, the pub, the airport, the truck stop.

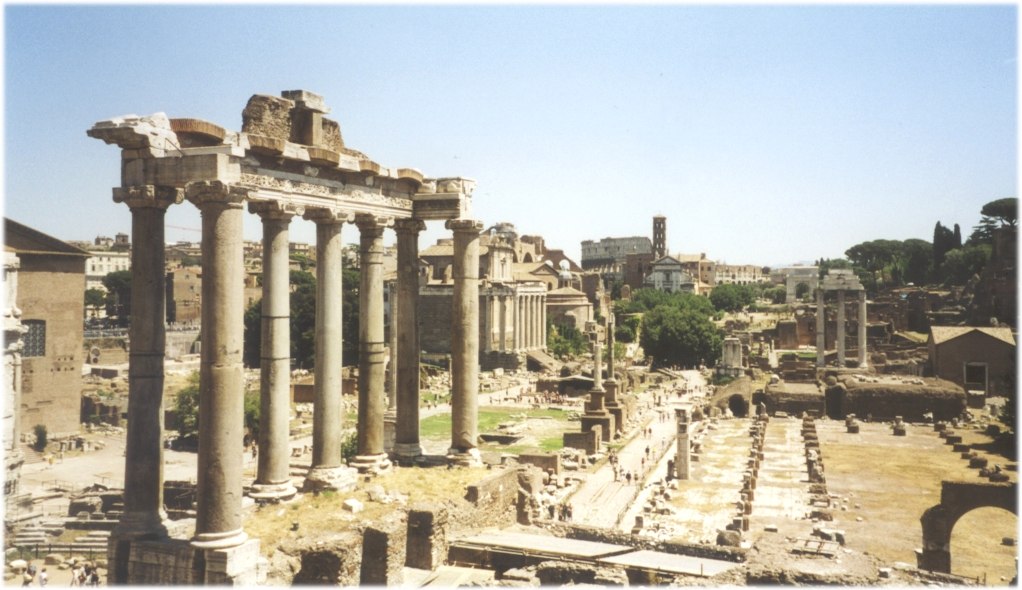

The mall’s status as a dominant liturgical center in our culture (which Jamie Smith has discussed at length in Desiring the Kingdom) just becomes even more entrenched, in other words. When the church is co-opted in this way, it ceases to be a distinctive, separate political society and simply becomes one more failing social group, indistinguishable from any other. Yet scripture refers to the church alternatively as “aliens” and “strangers,” words that suggest the distinctiveness of our community and the message that explains it. Our ability to speak “compassionately” and “prophetically,” in Webster’s phrase, hinges on this point.

Obviously the point is not to be different purely for the sake of being different. Rather, it’s that the liturgy is able to cultivate a unique kind of difference that is in fact near the heart of Christian faith. The liturgy is where we hear the Gospel, the proclamation of a kingdom in which the first shall be least and where we receive the sacraments that animate and promote this life within the church. It is the place where the church learns how to be different in the way that a Gospel-believing people must be different. If the distinctiveness of that liturgy and the message it conveys is lost, then the church has nothing left to give to the world because, as Christopher West is fond of saying, you cannot give what you do not have.

This is where some well-meaning proponents of both the New Evangelization and of Missional church practices begin to go wrong. The logic of these unconventional worship services seems to be rather simple: if we can’t bring the people to us, we go to the people. So rather than trying to drag an unwilling populace to the church building, the church seeks to bring the church building—or at least what goes on in a church building—to them. But what thought has been given to the question of what is lost when the liturgy is moved into a new and foreign environment? What happens, as I already asked, when the week’s sermon text is on the sin of avarice and the site of said service is the mall? (We do still preach against avarice, I hope?) How does a public confession of sin happen in a pub? And how can it be done in a way that isn’t rude or intrusive toward the other guests? As someone who heard many an obnoxious Bible study in the coffee house near campus during undergrad days, church in a pub seems like an even more obnoxious version of the same.

And what about the Eucharist? Can you properly fence the table so that people who shouldn’t receive the elements are excluded? What of baptism? Thinking more broadly, what is lost when we move the church’s sacramental life into a location shared with a common business during its business hours? (I understand that for some churches there is the inevitable problem of needing somewhere to worship and so they lease a conference room at a hotel or classroom space in a school. That, however, seems different from willfully choosing to meet in a pub during business hours or meeting at the mall during shopping hours when you don’t have to.)

The points above raise a mixture of logistical and environmental problems. In some cases, it’s just a matter of understanding how something central to a church’s life, such as baptism, can function in a place that doesn’t have an altar or baptistry. In other cases, it’s a problem of environment—certain places suggest certain uses. You don’t go to the bar at 11 p.m. on Saturday night to study for your chemistry test, and you don’t go to the museum to toss a football around with some friends. The design and shape of a given place suggest an intended use for that place—and while those uses aren’t written in stone, they do tend to imply certain limits to what you can do with a given space. And the reality is that as much as we might like to think (in our modernistic pride, most likely) that we can ignore such conventions to serve a greater good, like bringing the Gospel to our neighbors, I doubt that that is true in practice.

It’s possible, to be sure, that the words of the text proclaimed in the liturgy might take on a new life and relevance when placed in a different, unfamiliar place. But I suspect such cases would be the minority and the more common result would be the watering down or subtle altering of the message to align with the life of the place in which the message is being proclaimed. As Churchill said, we shape our buildings and then our buildings shape us. It is far more likely that the space in which that message is proclaimed will have the effect of rendering it impotent. Consider, for instance, what the market has done with so many of the one-time counter-cultural bands of the ‘60s and ‘70s: you can now find Led Zepplin and Pink Floyd t-shirts on the racks at Target. And a few years ago we got to hear a 60-something Roger Daltrey sing, “hope I die before I get old,” as part of the Super Bowl halftime show. To slightly adapt McLuhan’s famous words: Messages imply mediums for conveying the message. When the medium is altered or completely turned on its head, the message itself is seldom left untouched.

Within Christianity, the liturgy carries an enormous weight. The liturgy is the place in which the church is reminded of its uniqueness, in which its message is proclaimed, and in which its people are formed into the image of Christ. It is, perhaps most importantly, the place in which we receive the sacraments that enable us to live the Christian life in the world. These ritualistic customs have a function important to any social group—inculcating the group’s beliefs and way of thinking in its members. How much greater, then, must the impact of these rituals be when the rituals are handed down to us by God himself and carry with them the power to restore the image of God in human beings?

It is almost certainly impossible to overstate the importance of public worship and the liturgy in the church’s life, particularly in a setting where the church is a social minority and where its beliefs and life are often questioned and undermined by larger social bodies. It is the distinctiveness of the Gospel that is its power, its Otherness that provides the rationale for going into the world. If that uniqueness is lost, then we go into the world with nothing to share but another sanitized, sterilized religion, deprived of its ability to produce any genuine change in individuals or in communities.

Yet there is a second question to discuss as well—if the Otherness of the Gospel must be emphasized and made much of in the Liturgy, then where can the ordinariness of Christian piety be seen? The point, as I have said, is not to be different for the sake of being different, but to be different in a way that is lively and vibrant, that reflects the depth and beauty of the Gospel. This implies that the church must live its life in the world amongst those outside the church. So how then can a church so committed to being liturgically distinct maintain its contact with the world outside?

The ironic answer: We do it in the very places where the liturgy is currently being misappropriated. The way to bring the Gospel into contact with the people going to a pub or shopping in a mall is not to drag the liturgy kicking and screaming into those places, futilely pounding a stubbornly square peg into an undeniably round hole. The far simpler and more glorious answer is that Christian faith is brought into those spaces by the members of the church faithfully living out the implications of Christ’s resurrection throughout all of creation. Christ’s resurrection represents both the affirmation and restoration of creation, so Christians can go into the streets and the marketplace without fear. We can go boldly, empowered by a quiet confidence in the goodness and sovereignty of God to promote and preserve his work in the world.

We don’t need to drag the liturgy into pubs, but we most certainly should bring ourselves into pubs as good customers and members of the community. In the absence of a good pub, we should open pubs and create genuine third places where civil society can grow and thrive. These kinds of good works in the world are what the church ought to be about in relationship to its neighbors. But if we lose touch with the liturgical differences in which our community is based, then we will lack the intellectual, social, emotional, and spiritual resources needed to be this sort of people. Good works done outside of the church flow from a vibrant life of Christ within the church. As C.S. Lewis famously said, aim for heaven and you get earth thrown in—aim for earth and you get neither.