Why Place Matters edited by Wilfred McClay and Ted McAllister

As a Southern man living in New England, I think often about place. My bookshelf betrays my interest in the my home region, displaying I’ll Take My Stand: The South and the Agrarian Tradition alongside Toole’s Confederacy of Dunces, Faulkner’s The Unvanquished, and O’Connor’s The Habit of Being. I speak frequently about life south of the Mason-Dixon, from its “Yes, ma’am” and “Praise Jesus!” to its heavenly cuisine and natural beauty. Occasionally, I am called to explain its painful history or its present woes. Recently, I have enjoyed reading the stories of hospitable neighbors and strangers, who opened their doors to help those stranded by exotic snowstorms in the Deep South. And yet, as I honor my Southern roots from my residence on the North Shore of Massachusetts, I remain open to what I owe this place that is not my home and what its culture and traditions have to teach me.

In Why Place Matters, editors Wilfred McClay and Ted McAllister offer a welcomed contribution to thinking more deliberately about place and its relation to human flourishing. One cannot help wondering, however, if the appearance of a volume like Why Place Matters is not already an indictment of the age from which it emerges. Could there be anything more basic to human experience and less in need of apologia than the reality of place, of natural and cultural embeddedness? But if, as French intellectual Paul Valéry supposed, the essence of modern culture is “interchangeability, interdependence, and uniformity,” then a defense from the roots and the soil of life seems vital.

Both the editors and most of the contributors to this volume remain sympathetic to a conservative recovery of place—and, in full disclosure, so does this reviewer. In many respects, the countercultural tone of the work is reminiscent of Russell Kirk and his appropriation of his friend T.S. Eliot’s “permanent things.” The editors argue that in our progressively globalized, digitized, and mobile world, “we risk forgetting this reality of our embodiment.” From this deep perspective on situated place, the book administers prophetic critique rather than wallowing in “nostalgia” (a word that has somehow, metonymically, become a coup de grâce in many discussions).

Every chapter is itself worth the price of the compendium, and the cross-disciplinary research of the various articles redounds to the benefit of the reader. One important propaedeutic couched in McClay’s introduction must be underscored: While the American story can (according to some popular and uncomplicated narratives) pit place against freedom, this sort of manufactured and overwrought antithesis lives ten feet off the ground. Ultimately, the false contrast of limitation and limitlessness does a fair bit of damage to sober ethical reflection. Besides, other questions are more relevant, such as the deflation and homogenization of cultural diversity by the global marketplace, and the devaluing of civic engagement in the era of “digital citizens.” (As one Microsoft website casually inquires of the online individual, “What does digital citizenship mean to you?”)

In a particularly superb chapter, Philip Bess addresses architectural opportunities from a metaphysical foundation. Bess is one of the most important living American traditionalist architects, a member of the New Urbanism movement, a Catholic and the Director of Graduate Studies in the School of Architecture at the University of Notre Dame. In his chapter, he argues for walkable neighborhoods, durable construction, and integrated communities of mixed commerce, leisure, and historical awareness. In contrast to the faceless spirit of suburban sprawl, Bess advocates for the propriety of traditional, working-class neighborhoods and small-town front porches.

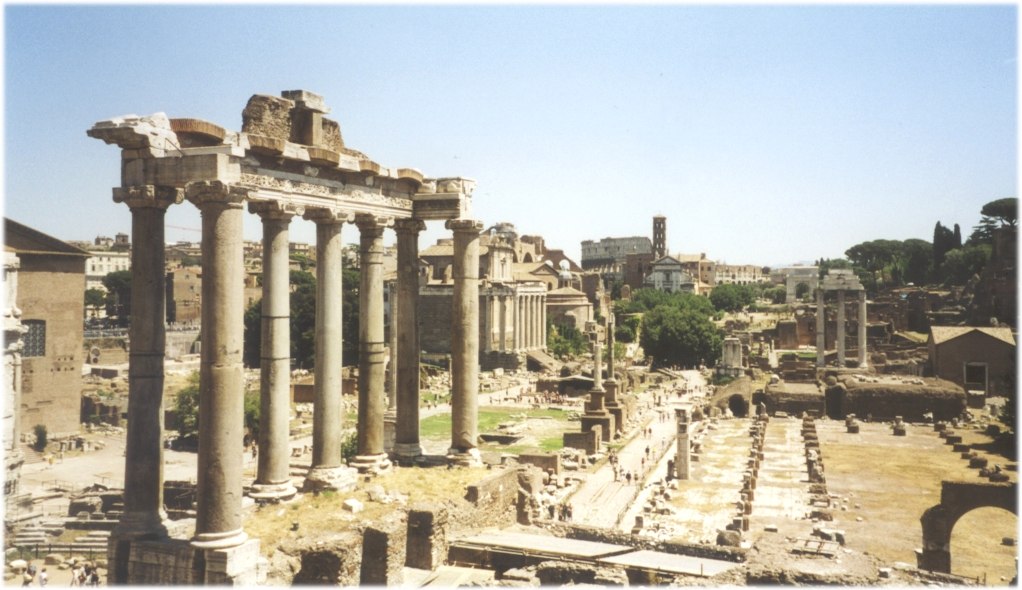

According to Bess’s article, “Metaphysical Realism, Modernity, and Traditional Cultures of Building,” all architectural theory and urban design entails worldview. Every architectural development and urban plan accentuates a particular understanding of the telos of man, community, society, and environment. As a prior arrangement and counter-proposal to modernity, traditional architecture takes seriously the telos of human well-being and natural-aesthetic habitation. Indeed, Bess insists,

[T]he best life for individual human beings is a life of moral and intellectual excellence lived in community with others, and most typically in a town or city neighborhood—that is, in a finite and generally bounded place with some degree of geographic character and specificity.

This approach considers acutely what is being communicated within a specific place, how that message shapes the residents and culture in that place, and how it evolves and adapts through time. To that end, it grounds itself upon a common-sense philosophy called metaphysical realism, which assumes that “the world is real, that we can know the world truly, and that we flourish by conforming ourselves to reality.” As Bess points out, modernity denied not only the reality of the world, but also the epistemological basis for knowing reality and the virtues of respecting whatever it might be. Traditionalist architecture, therefore, enlists the social and intellectual resources of classical culture and Biblical religion, which overwhelmingly witness to a metaphysical realist position contra the unsustainability of modernity itself.

Other chapters focus on the rebirth of localist politics, the joys of local histories, and the positive impact a renewed sense of place can have on the problems of poverty. However, one glaring blind spot in the collection of essays is the matter of theology. This is a missed opportunity. The sudden flurry of interest, discussion, and publication by evangelical Christians with regard to “the city”—and those reacting to this surfeit of attention—seems entirely germane to identity and civic life in modern America. For ill or well, a surplus of books like Why Cities Matter: To God, the Culture, and the Church or Center Church: Doing Balanced, Gospel-Centered Ministry in Your City are now resting on the bedside tables of Evangelicals. Fare Forward itself published a whole issue on the subject. Some form of theological reflection could have added another important layer to this conversation on place. That said, all in all, Why Place Matters is an excellent resource and a hopeful sign in a time of de rigueur excess and self-indulgence.