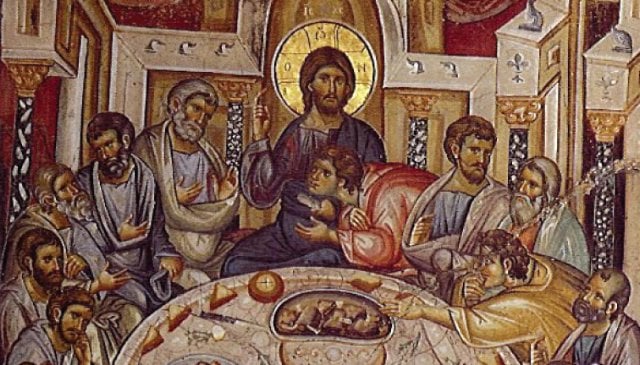

Growing up, my church observed “Lord’s Supper” once a quarter. Every three months, an extra line would appear in the bulletin’s Order of Service between “Message” and “Special Music.” After spending a silent minute “examining our hearts,” trays bearing a species of super-dense oyster crackers and tiny plastic cups of grape juice would be passed along the pews, offering plate-style. In a tradition that generally deprecated ritual, this practice was clearly an anachronism, a holdover that would have been mildly embarrassing if not insulated from inspection by a thick coat of cognitive dissonance. What it all meant I couldn’t have told you, other than that it had something to do with “remembering Jesus.” Were we in danger of forgetting him?

It wasn’t until I got to college that I began attending a church that observed “Communion” weekly. The procedure was relatively similar; the cups’ contents remained unfermented though the oyster crackers were replaced by shards of matzo. Around the same time, I got to know my first Catholics, an exceedingly rare breed in my corner of the world. Soon, I gained a great appreciation for the Catholic tradition, including the centrality of the “Eucharist” to their worship. At our church here in Knoxville, Communion features actual wine and involves leaving one’s seat to participate. So you could say I’ve come a long way.

Over time, with a weekly observance of Communion and a thicker understanding of its theological significance, my attitude toward the sacraments and other liturgical practices changed. Certainly, there is an experiential dimension to this learning process, but I believe there is a communicable component as well. A more serious engagement with the sacraments has expanded my sense of the way God changes us.

Before engaging with the sacraments, I thought about grace almost exclusively in terms of the forgiveness of sins. The accompanying images were of removal: “Purge me with hyssop, and I shall be clean; wash me, and I shall be whiter than snow.” Sin was an accumulation of spiritual tarnish that grace polished away. Certainly, this picture of grace as a subtractive process is both Scriptural and valuable. But I have come to believe that it is incomplete. For one thing, an exclusive focus on grace as forgiveness implies that except for our assorted wrongdoings, we are basically whole and healthy. On the one hand, I understood that was inaccurate: the phrase “spiritual growth” was in my religious vocabulary. But I lacked a vision for how grace operated not merely to cleanse but also to edify.

The act of eating, as appropriated by the Communion rite, makes this other aspect of grace unmistakeable. As C.S. Lewis puts it, God “uses material things like bread and wine to put the new life into us.” This correctly pictures our incompleteness, our brokenness and hunger, our need for God that exists apart from our need for forgiveness. Grace builds us up in addition to washing us off. In receiving grace as sustenance, we are called into a more substantial life; like the narrator in The Great Divorce, we are becoming more solid as we draw near to God. On the macro-level, the additive view of grace prepares the mind for the restorative view of God’s work in history, that he not only defeats death but fosters abundant life.

Of course, the tradition I grew up in was not entirely without additive spiritual practices. The study of Scripture was commonly discussed in quasi-sacramental terms. But while I think, like the subtractive picture of grace, the notion of feeding on Scripture has both spiritual and practical value, I think the sacraments offers something more in their very mysteriousness. We naturally understand that filling our heads with holy writ could tend to give us the mind of Christ. But that by filling our stomachs with bread and wine we partake in the divine life comes as something of a surprise. It reminds us of our need for God to act on us and for us, that grace is an intervention. It cures us of our native Pelagianism.

I fully understand that, for many traditions, the mechanics behind the transmission of grace through the sacraments are of great importance. While I don’t particularly share that concern, I respect that opinions differ. My hope is that this is one of many areas in which a thicker Christian practice will develop across denominational lines. Speaking from personal experience, I believe there is much to be gained even by those like myself who find it convenient or necessary to bracket the theological details.