I recently wrote about an interview I conducted with sociologist Robert Bellah in preparation for a talk he gave this past week at Notre Dame. The talk introduced his thoughts on the next step in his work, following up on his argument in Religion in Human Evolution.

A good portion of the talk drew on recent work by Ian Morris on the historical relationship between development and the fate of civilizations. In particular, Bellah found that a developmental “hard ceiling” consistently held across all civilizations until the modern era. Put simply, Morris’s measure of development tops out at the same value in every case until the technical developments of the Industrial Revolution. Subsequently, we have witnessed an unlimited scaling of development that has shown no sign of slowing down. Another significant factor in determining our modern condition, according to Bellah, is the “sacralizing of the person” that accompanied these technical developments. The combined result has been an incredible race toward what Bellah fears may be the “mother of all hard ceilings.”

What I found most interesting was not simply the dire circumstances that Bellah described, but the strong sense of inevitability. It is almost as if knowing about the hard ceiling doesn’t matter, or that the drive to grow and prosper overrides anything else, continually resulting in civilizations consuming themselves.

Self-destructive desires? Suicidal drives to prosper? Myopic pursuits of gain? I couldn’t help but see in Bellah’s description a remarkable sociological account of sin nature. That humanity, given sufficient resources, will prosper itself into destruction sounds like proper orthodoxy.

But more importantly, it may point to a significant role that Christian views of human nature could play in influencing the discourse about humanity’s future. It is clear, by a number of measures, that we can’t keep on as we always have, but we need better ways of thinking about how and why to make things better. It isn’t merely about scare tactics. It’s about the full realization of what we are meant to be as persons: not acquisitive, consuming, hyper-individuals, but balanced, creative, and communal members of one another.

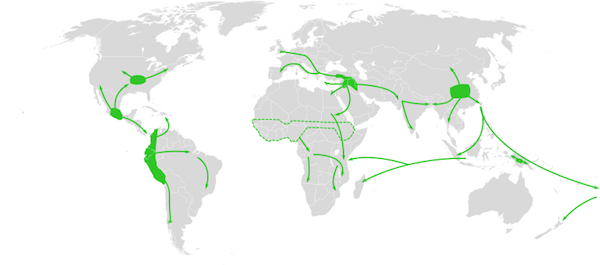

[Map of the Spread of Agriculture Courtesy of Wikipedia]