We live in a moment that is at once pervaded by guilt and dismissive of its reality. This was the paradox set forth by Wilfred McClay last Thursday in his talk, co-sponsored by Trinity Forum and the Pepperdine University, “The Strange Persistence of Guilt in a Post-Religious World: How it Affects our Public Life, and What We Can Do About It.”

McClay notes that his students seem to be feel guilty about almost everything: colonialism, environmental problems, structural poverty, and so on. This enlargement of our sphere of responsibility speaks to civilizational progress: not only do we now have access to stories about a starving child in Africa, we also generally possess the means to fly over and help him. This creates overwhelming, omnipresent sense that any help we can give is “never enough.”

We do not have adequate means of managing this guilt. Moderns operate in a “nonjudgmental therapeutic worldview” which treats guilt as a trap. “Forgiveness” has lost much of its moral value, as it is seen mainly as a way for you to “move on,” instead of a gesture of “transcendent and unconditional regard for humanity.” So we do the only thing left to us: we claim “victim” status. At least the victim is free from any responsibility or guilt.

Our modern quest for absolution for our guilt, freed from the Christian narrative of a God who recognizes our guilt and atones for it through the payment of his life, is futile. But simply accepting this narrative isn’t a cure, either. Many young Christians who do believe in the atonement of Christ still struggle with the pervasive, nagging sense of guilt. They feel like they aren’t doing enough to help the environment or the homeless person they just passed by.

One way to start addressing this is to make a distinction between “concern” and “responsibility.” In a short talk he gave at the Trinity Forum Academy, Skip Ryan argued that Christians and citizens ought to have large circles of concern, of causes and peoples that concern us, but we also have to draw a more narrow circle of responsibility within that large circle. We are called to address only those concerns that fall within our “responsibility,” and everything else we entrust to God.

But how do we know what counts as a mere concern and what counts as a responsibility? The first thing to note is that extending the boundaries of our responsibility might only dilute it. This is what Stephen Asma, author of Against Fairness, argues in a NYTimes op-ed this past January. He offers a hyperbolic anecdote to demonstrate the impossibility of making decisions if one widens one’s circle of responsibility globally:

Say I bought a fancy pair of shoes for my son… I should probably give these shoes to someone who doesn’t have any. I do research and find a child in a poor part of Chicago who needs shoes to walk to school every day. So, I take them off my son (replacing them with Walmart tennis shoes) and head off to the impoverished Westside. On the way, I see a newspaper story about five children who are malnourished in Cambodia. Now I can’t give the shoeless Chicago child the shoes, because I should sell the shoes for money and use the money to get food for the five malnourished kids.

And so he goes on, arguing from evolutionary biology that care is a “limited resource” which can realistically only extend to your “tribe,” whether that’s your neighborhood, extended family, or workplace. Having a narrow circle of responsibility means a capacity for deeper, more sacrificial care, as opposed to a thin, watered-down care that is spread over the masses.

This perspective recalls a quote by Dostoevsky:

“It’s just the same story as a doctor once told me,” observed the elder. “He was a man getting on in years, and undoubtedly clever. He spoke as frankly as you, though in jest, in bitter jest. ‘I love humanity,’ he said, ‘but I wonder at myself. The more I love humanity in general, the less I love man in particular. In my dreams,’ he said, ‘I have often come to making enthusiastic schemes for the service of humanity, and perhaps I might actually have faced crucifixion if it had been suddenly necessary; and yet I am incapable of living in the same room with any one for two days together, as I know by experience. As soon as any one is near me, his personality disturbs my self-complacency and restricts my freedom. In twenty-four hours I begin to hate the best of men: one because he’s too long over his dinner; another because he has a cold and keeps on blowing his nose. I become hostile to people the moment they come close to me. But it has always happened that the more I detest men individually the more ardent becomes my love for humanity.”

Dostevsky is making a Christian critique, but other aspects of Christianity seem to complicate this. As much as Christians can agree with Asma’s call to commit to and care for local community (as against “universal humanity”) we can’t avoid the fact that Christ’s calls us to leave our comfortable tribes and make disciples of all nations.

Should we then adopt a universalistic or a tribe-based calculus in deciding our circle of responsibility? It’s a difficult question, one that I would love people’s thoughts on in the comments section. On one hand, Paul the apostle seems the model of efficiency and universal care, traveling through multiple countries in order to plant churches. On the other hand, Mary poured an extravagantly expensive perfume on Jesus’ feet, and her story is told whenever the Gospel is preached.

Wherever you end up on the spectrum, a utilitarian calculus that tries to adopt the “optimal” perspective in order to produce “maximum care” should hold no temptation for us. Such a calculus presumes an omniscience that belongs to the One who called both Mary and Paul.

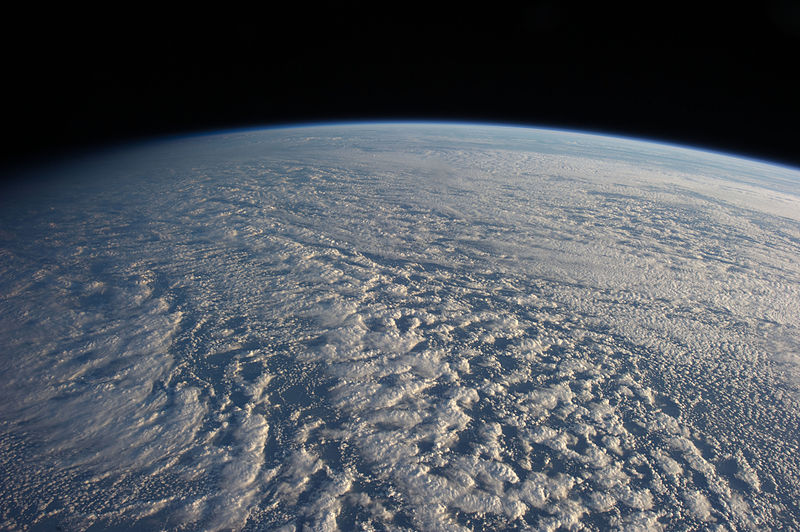

[Image of the Earth Courtesy of Wikipedia]