While the show’s premise is rooted strongly in secular humanism, Star Trek is, at the same time, profoundly concerned with issues of truth and morality. But only to a point.

While the show’s premise is rooted strongly in secular humanism, Star Trek is, at the same time, profoundly concerned with issues of truth and morality. But only to a point.

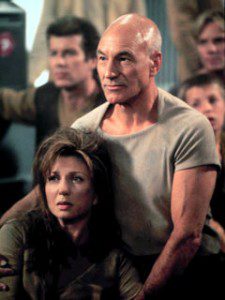

Star Trek: Insurrection, the latest movie in this TV and film franchise, offers a striking case in point. In it, Captain Jean-Luc Picard (played by Patrick Stewart) discovers that the Federation is secretly planning to relocate an alien race, the Ba’Ku, against its will. This is in violation of the Federation’s Prime Directive, which prohibits interference with alien cultures, but Picard’s superior officer, Admiral Dougherty (Anthony Zerbe), rationalizes that it is a trivial matter: the Federation would be moving only 600 people.

To this, Picard angrily replies, “How many people does it take, Admiral, before it becomes wrong?” He throws out several numbers (a thousand? a million?) and, in doing so, makes a mockery of Dougherty’s relativism. In this instance, at least, morality is absolute — forced relocation is either wrong or it is not. The rest of the film follows Picard as he mounts a rebellion in defence of this higher law.

But where there are laws, there is also, implicitly, a law-giver. And this is where Star Trek hedges its bets. When Picard and his crew look for moral justification, they turn to the emotionless android, Data (Brent Spiner). Presumably we are to think that Data arrives at his opinion through purely rational means. But earlier in the film, there is talk of Data’s “ethical and moral subroutines” which enable him to distinguish between “right and wrong.” Data’s sense of morality has been programmed into him, and it is, therefore, Data’s creator who ultimately justifies Picard’s rebellion. By extension, one might ask where humans get their own sense of morality.

This question, among others, is raised in The Double Vision of Star Trek, an analysis of the series from a Christian perspective. Mike Hertenstein, editor of Cornerstone magazine, suggests that Star Trek is “a bundle of unresolved tensions” and that it suffers from “a chronic guilty conscience” because it cannot reconcile these tensions without “cheating.”

For example, Star Trek loves to celebrate the triumph of the human spirit, yet in episode after episode, the day is saved by last-minute bursts of technobabble — what Mr. Hertenstein calls the show’s central deus ex machina. Moreover, whereas Trek history was once built on the humanistic premise that humans achieved peace on their own before heading into space, the film Star Trek: First Contact reveals that the world was essentially saved by the arrival of “alien messiahs” in our near future — another deus ex machina.

Other contradictions abound. The good guys champion cultural tolerance in the extreme — most famously in the Vulcan motto “Infinite Diversity in Infinite Combinations” — yet they don’t seem to approve of tyrants or Klingon ritual murder. Apparently, even infinity has its limits. Then there is the show’s uneasy relationship with technology. Trek characters who transfer their minds into computers inevitably lose the spark of life that defines their humanity. Yet Data and the holographic doctor on Star Trek: Voyager are accepted by most other characters as fully conscious persons in their own right; to support this view, Picard has argued that humanity is ultimately just another form of machine.

But what basis is there for morality within such a worldview? Here, too, Star Trek hedges its bets and resists carrying such strict materialism to its logical conclusion. Despite itself, the show operates on the gut instinct that there is something more to life, and there there are some things people should and should not do, no matter what the cost; indeed, in the recurring theme of self-sacrifice, author Hertenstein argues that Star Trek bears subliminal traces of the Gospel itself.

In essence, Star Trek raises an altar to an unknown god; with the help of writer Hertenstein, Trekkers may come to know him a little better.

— A version of this review was first published in BC Report.