Brazil has some of the most heavily populated cities in the world. It is also currently home to one of the largest religious revivals in the world. Central Station, the new film from Brazilian director Walter Salles, tells a familiar story — an old, cynical woman finds herself looking after a young boy and, in the process, she learns how to open her heart — but it makes use of its setting in an original and thoughtful way.

Brazil has some of the most heavily populated cities in the world. It is also currently home to one of the largest religious revivals in the world. Central Station, the new film from Brazilian director Walter Salles, tells a familiar story — an old, cynical woman finds herself looking after a young boy and, in the process, she learns how to open her heart — but it makes use of its setting in an original and thoughtful way.

Dora (Fernanda Montenegro) is a retired schoolteacher who makes her living writing and mailing letters for the illiterate customers who pass her way in a crowded train station in Rio de Janeiro. Sometimes a face stands out from the crowd; in fact, we see these customers dictating their missives before we see Dora herself. One man, smiling enigmatically, thanks someone for cheating him and robbing him of everything he owned; his message of grace and acceptance is a harbinger of things to come.

Dora, however, is not particularly moved by the insights she gets into the hearts and lives of her clients. In fact, she takes the letters home to her apartment and reads them to a friend; after theyve had a laugh or two, she sends the ones that, in her opinion, deserve to be sent, and she tears up or files away, indefinitely, the ones that fail to impress her.

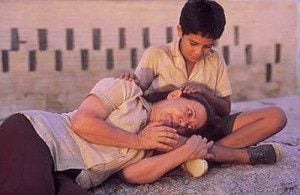

One day she takes dictation from a woman whose son Josué (Vinicius de Oliveira) wishes to meet his father, a man named Jesus (who already has two adult sons named after Moses and Isaiah). However, the woman is killed in a traffic accident on the way out of the station, and Josué is left behind to fend for himself. Dora reluctantly takes him under her wing and, together, they take a journey out of the city in search of his father.

The story from here is relatively predictable, so its up to the actors to keep things personal and interesting. Montenegro, as Dora, definitely achieves this; her expressive features convey at times a resigned world-weariness, and at other times — later in the film — the beginnings of a more radiant joy, and its a pleasure just to watch her come alive.

De Oliveira is less successful, and Im not sure whether its due more to the character, who is kept somewhat at a distance by his precocious sense of juvenile machismo, or to the performance, which lacks the heart-breaking emotional force of, say, the child in Kolya.

The film also makes distinctive, and prominent, use of religious themes and characters. Dora and Josué are helped at one point by an evangelical truck driver, whose generosity is ultimately compromised by his all-too-human fear of moral failure. Later, Dora reaches a crucial turning point in the midst of a Catholic revival ceremony, where worshippers loudly call on God to pierce the darkness of their souls with his Light.

There is no explicit conversion scene here. Dora herself does not directly call out to God, as such, but she is overwhelmed by the prayers of those surrounding her; it is almost as if she benefits from Gods grace by osmosis. And, in the end, she becomes an agent of that grace herself.

The film, in its own allegorical way, looks forward to the day when we will all see Jesus face-to-face, and it paints a touching and poetic portrait of the faith, hope and love that can come to us while we wait.

— A version of this review was first published in ChristianWeek.