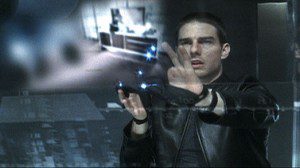

Steven Spielberg hasn’t got Stanley Kubrick out of his system yet. In some respects, Minority Report is the sort of futuristic sci-fi chase movie that makes popcorn vendors smile. It’s also the sort of spectacular summer flick you expect a crowd-pleaser like Spielberg to excel at. But it also reflects the bleak, dystopic vision of things to come that made A.I. Artificial Intelligence, Spielberg’s realization of a project Kubrick spent years developing, so chilling and unfamiliar. Minority Report also stars Tom Cruise, who earned a place in the Kubrick canon with Eyes Wide Shut, and it puts him in a situation that calls to mind one of the more freakish and uncomfortable moments in A Clockwork Orange.

Steven Spielberg hasn’t got Stanley Kubrick out of his system yet. In some respects, Minority Report is the sort of futuristic sci-fi chase movie that makes popcorn vendors smile. It’s also the sort of spectacular summer flick you expect a crowd-pleaser like Spielberg to excel at. But it also reflects the bleak, dystopic vision of things to come that made A.I. Artificial Intelligence, Spielberg’s realization of a project Kubrick spent years developing, so chilling and unfamiliar. Minority Report also stars Tom Cruise, who earned a place in the Kubrick canon with Eyes Wide Shut, and it puts him in a situation that calls to mind one of the more freakish and uncomfortable moments in A Clockwork Orange.

One thing Minority Report lacks is Kubrick’s risk-taking genius. The film is based on a short story by Philip K. Dick, the metaphysically minded sci-fi author whose works also inspired the mind-bending exploits of Blade Runner and Total Recall, and like those other films, Minority Report is concerned with questions of identity and free will. But it never gets into these themes as deeply as it should. Instead, it divides its time between generic action sequences and chatty scenes in which characters try to explain the film’s convoluted premise. The film tries too hard to make itself work, and doesn’t quite succeed.

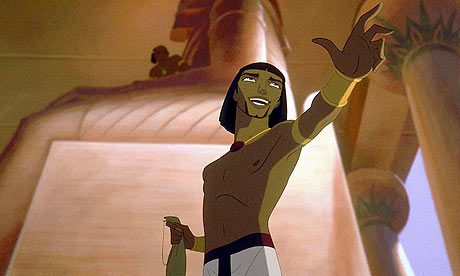

The story takes place about 50 years in the future. Cruise plays a cop named John Anderton who works for an agency that has virtually stamped out murders in Washington, D.C. by predicting when they’ll happen and intervening to prevent them. How the agency anticipates these crimes is complicated: Two men and a woman, apparently the product of genetic research performed on the children of drug addicts, have acquired psychic powers that enable them to see murders up to four days in advance; if the murder is a crime of passion, they may have only a few hours’ warning. These three “pre-cogs” are kept in a lab with computers hooked up to their brains that turn their visions into 3-D crime-scene images, which agents like Anderton manipulate to determine where the crime is about to be committed. The would-be culprits are then apprehended and imprisoned in a sort of suspended animation, where they are presided over by an organ-playing goofball named Gideon. The system has its critics, but everything seems to be working-that is, until Anderton learns he may be the next murderer, and his predicted victim is someone he’s never heard of before. Hunted by his former colleagues, and convinced that he’s been set up by a new detective, Anderton runs for his life.

Thanks to current events, the film’s stark portrayal of a world where privacy and the presumption of innocence have been abandoned, in the name of public safety, has a new urgency. In this future setting, everyone’s information is kept in a central databank, and sensors scan the retinas of passers-by to keep track of their movements. If the cops want to search an apartment, they send little spider-shaped eye-scanning robots under the door to interrupt, without warning, people who may be sitting on the john or making love. What’s more, advertisers have access to this data, too, and Anderton can’t go anywhere without being followed by animated posters that call his name.

Spielberg blends the effects so seamlessly into the rest of the film that you almost take them for granted; on a technical level, the film is flawless. Max von Sydow and Samantha Morton also give effective supporting performances, he as Cruise’s mentor, and she as the female “pre-cog” whose memories of the future may hold the key to unravelling the conspiracy against Anderton. But the script, by Scott Frank (who wittily adapted the Elmore Leonard novels Get Shorty and Out of Sight) and newcomer Jon Cohen, feels like a regurgitation of other movies. One major third-act revelation isn’t the big shock it was meant to be, and the surreal scene in which Anderton has his eyeballs replaced by a back-alley surgeon (Peter Stormare) is full of artificially contrived dramatic friction that goes nowhere.

The film’s biggest problem is that it gets bogged down in the mechanics of precognition, which leaves you wondering whether the film adhered to those mechanics in the first place. To say any more would give away the plot, so suffice it to say this may be Cruise’s most puzzling and disappointing head-scratcher since the original Mission: Impossible.

— A version of this review was first published in the Vancouver Courier.