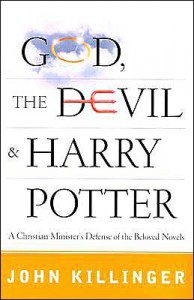

• John Killinger: God, the Devil & Harry Potter, St. Martin’s, 2002.

• John Killinger: God, the Devil & Harry Potter, St. Martin’s, 2002.

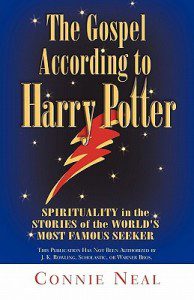

• Connie Neal: The Gospel According to Harry Potter, Westminster John Knox, 2002.

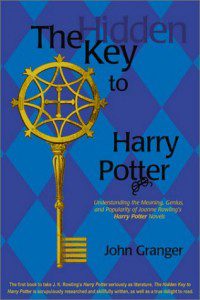

• John Granger: The Hidden Key to Harry Potter, Zossima, 2002.

CHRISTIAN Harry Potter fans, unite!

It has been over two years since Richard Abanes wrote Harry Potter and the Bible: The Menace behind the Magick, a scathing critique of just about everything to do with J.K. Rowling’s bestselling series about an orphaned English boy who goes to a boarding school for witches and wizards.

Since then, no one has really added to Abanes’s criticisms, but quite a few Christians have lined up to defend Rowling and her books against the accusation that they are simply trying to warm children up to the sort of real-life occultic practices that are forbidden in the Bible.

Three recent books underscore the positive, and even Christian, elements in the Harry Potter books, but they do so from very different points of view.

John Killinger, a Congregationalist minister with doctorates in theology and literature, takes the liberal Christian approach in God, the Devil & Harry Potter. He says Rowling’s books grow out of a Christian understanding of the world but ultimately point to a spirituality that transcends any particular religion.

According to Killinger, Greeks and Romans saw the world as a series of struggles but did not think of the struggle as one between good and evil until Christianity came along; and he says the Potter books appeal to children because they, unlike many adults, still have a deep awareness of this hidden struggle within our world.

Killinger notes how many of the creatures and symbols in Rowling’s books actually come from medieval Christianity; and, borrowing a phrase from Henri Nouwen, he argues that Harry Potter, who bears a scar on his forehead from his first encounter with the evil Lord Voldemort, may be a “wounded healer” like Christ.

The Harry Potter books, Killinger says, are a hit because they go beyond the materialist assumptions of our age and they put us in touch with “the magic and mystery of life, the dimension beyond the ordinary, the sense of wonder that makes even commonplace experiences shine with the brilliance of celestial bodies.”

So far, so good. However, Christians of a more traditional persuasion may take issue with Killinger’s theological reliance on Marcus Borg and Matthew Fox; with his historical skepticism regarding the Gospel of John; or with the way he waffles on the resurrection and says the appearances of Christ are just one example of how the dead stay in touch with the living.

Connie Neal takes a more evangelical approach in The Gospel According to Harry Potter, though she does not offer a critical analysis of Rowling’s books per se — she already did that two years ago, in What’s a Christian to Do with Harry Potter? Instead, this time, she quite openly reads her Christian faith into the books.

Connie Neal takes a more evangelical approach in The Gospel According to Harry Potter, though she does not offer a critical analysis of Rowling’s books per se — she already did that two years ago, in What’s a Christian to Do with Harry Potter? Instead, this time, she quite openly reads her Christian faith into the books.

According to Neal, the magic in Rowling’s books is pure make-believe, and if Abanes and other critics see real-world occultism in the books, then it is because they really want to find it there and they are reading the books selectively to prove their point. In response, Neal asks whether it is possible to use this approach to find the gospel in Rowling’s books as well.

Neal certainly draws some interesting parallels between the books and Christian faith, noting, for example, that people will try to flee God just as the Dursleys tried to flee Dumbledore’s letters, and that the tension between choice and destiny in Harry’s experiences with the Sorting Hat reflects the deeply Christian paradox of free will and predestination.

However, despite the valid analogies she draws, Neal’s book does suffer from a tendency towards utilitarianism — rather than explore the Potter books as literature on their own terms, she looks for ways that Christians can use them to explain the faith or to make converts.

Those seeking deeper insights into the Potter series should check out The Hidden Key to Harry Potter by Orthodox author John Granger (no relation to Harry’s friend Hermione!). Granger is a shameless self-promoter and his writing style is a tad insouciant for my tastes, but he does the best job so far of unpacking the Christian themes that underlie these stories.

Those seeking deeper insights into the Potter series should check out The Hidden Key to Harry Potter by Orthodox author John Granger (no relation to Harry’s friend Hermione!). Granger is a shameless self-promoter and his writing style is a tad insouciant for my tastes, but he does the best job so far of unpacking the Christian themes that underlie these stories.

Whether Rowling intends for her books to have these Christian themes, or whether they simply reflect her love of British culture and tradition, is of course open to debate. For his part, Granger argues that Rowling is a “closeted Inkling”, that is, a Christian writer like C.S. Lewis or J.R.R. Tolkien who hopes to baptize the imagination through Christian symbols and by encouraging the reader to choose virtue just as Harry Potter does.

Like Killinger, Granger notes that many of the creatures and objects in the Potter books have special Christian significance, especially when they are seen through a medieval lense. Griffins, unicorns, centaurs, stags, the phoenix, even the philosopher’s stone — all of these things represent Christ in some way, he argues.

Granger also notes that every book so far ends with Harry symbolically going through death and resurrection, usually by descending underground to confront the villain and then rising to the surface again; and he makes a compelling argument that the relationship between Harry and his two best friends, Ron and Hermione, symbolizes classical Christian beliefs about the need for harmony between spirit, body, and mind.

Granger’s book does have its own weaknesses. Of course, it is too early to gauge the accuracy of his predictions for the remaining three books — though the next one, The Order of the Phoenix, comes out this Saturday — but some of his other guesses, like his theory that the vain professor Gilderoy Lockhart was inspired by the anti-Christian children’s author Philip Pullman, seem like a stretch.

Granger also claims Rowling’s books are a “broadside, Christian attack” against the naturalistic assumptions of modernity, but I wonder how accurate it is to label the books “anti-modern”, as Granger does. Lewis and Tolkien may fit that label, but not all that is critical of modernity is traditional, and it is at least possible that these books might best be described as “post-modern”; however, this is one option Granger never considers.

It is tempting to argue that all three of these authors have been caught up in the hype and are seeing what they want to see in the Harry Potter books. All three of them praise Rowling’s storytelling, and if there are any weaknesses in her stories — and I think there are, though I do like the books myself — you would hardly know it from reading these commentaries.

We’re still waiting for a more balanced critical appraisal of the Potter books. But positive Christian responses such as these do provide a welcome antidote to Potter’s more hypercritical opponents.

— A version of this article was first published in BC Christian News.