The first time I ever heard of Timothy Treadwell was when I read the opening paragraphs of Mark Steyn’s review of the Disney movie Brother Bear (2003):

I was interested to see that among the technical advisors who chipped in their two bits’ worth on Brother Bear to ensure the accurate depiction of the grizzlies was Timothy Treadwell, the self-described eco-warrior from Malibu who became famous for his campaign “to promote getting close to bears to show they were not dangerous”. He did this by sidling up to them and singing “I love you” in a high-pitched voice. Brother Bear is certainly true to the Treadwell view of the brown bears, though instead of his sing-songy professions of lurve Disney commissioned Phil Collins, who turned in a generic score in the obligatory World Muzak style — West African percussion, Orff-cuts of choral ululating, heavy lyrical metaphors in the paint-with-all-the-colours-of-your-wind vein, just the sort of stuff your average Inuit was listening to before whitey showed up and offered to trade the land for a couple of Bert Kaempfert LPs.

Timothy Treadwell would have appreciated the story. Just as Kenai woke up to find himself trapped inside a bear, so did Mr Treadwell find himself trapped inside a bear — though in his case he was just passing through. In September, a pilot arrived at the great bear expert’s camp near Kaflia Bay in Alaska to fly him out and instead found the bits of him and his girlfriend that hadn’t yet been eaten buried in a bear’s food cache. “He would say it’s the culmination of his life’s work,” said Jewel Palovak, a colleague of Treadwell’s. “He died doing what he lived for.” He always said he wanted to end up in “bear scat”, which seems a very odd thing for a fellow who claims to love bears to say. The one thing you can rely on if you let the bear eat you is that you’re signing his death warrant: once a bear’s known to have a taste for human flesh, Fish and Game officials seek him out and kill him, as happened to the one Mr Treadwell ended up in.

You’d have to have a heart of stone not to weep with laughter at the fate of the eco-warrior, but it does make Brother Bear somewhat harder to swallow than its technical advisor evidently was. (The central character is named after Alaska’s Kenai Fjords, where Treadwell did some of his communing.) I live among black bears, not brown ones, and, for example, while struggling to write my review of Bruce Almighty a few months back, I was entertained by a mother and cub rambling round my kids’ swing set just outside the window. Cute. But I wouldn’t start singing to them.

One of the paradoxes of films like Brother Bear is that the more earnestly they claim to respect animals the more pathetically they anthropomorphise them. Next to eco-Disney, Looney Tunes is profoundly respectful: Sylvester wants to eat Tweety, Wile E Coyote wants to eat Road Runner. To be sure, Sylvester dresses up as a bellhop to take Tweety’s cage down to the lobby, and Wile E Coyote orders elaborate contraptions from the Acme company, but that’s just a little humourous accessorizing of the core truth — that, for half a century, that puddy tat’s main interest in the bird has been to grab him and kill him.

By contrast, consider the moment when Kenai, having been transformed into a bear, meets a cuddly little cub, and they hook up together — as in Shrek, Ice Age and all the other animal-buddy road movies. In reality, if a male bear came across a motherless cub, he’d eat him. In some vague half-conscious way, Brother Bear understands that its ursine ur-text is a crock. That’s why, before Kenai turns into a bear, the bears we see are, broadly speaking, bear-like. But, when Kenai joins their ranks, he wakes up looking like Yogi and every bear from thereon in comes straight from Central Cartoon Casting.

Steyn’s caustic “heart of stone” comment aside, I quote this here partly because, as I mentioned a few months ago in my post on Madagascar, I’ve been following the portrayal of carnivores and their prey in cartoons for the past few years. Are other animals friends, or food? And how does one make the distinction?

But I also quote this here because the Associated Press has a story up now on the new Werner Herzog documentary Grizzly Man:

A new documentary about Timothy Treadwell, who gained notoriety for living and dying among Alaska’s grizzly bears, has many worried that the compelling close-up footage of the animals could inspire other misguided adventure-seekers to emulate him.

“Grizzly Man,” directed and narrated by Werner Herzog, relies on scenes from more than 100 hours of raw footage shot by Treadwell while he lived among the bears at Katmai National Park and Preserve on the Alaska Peninsula.

Treadwell, 46, and his girlfriend, Amie Huguenard, 37, both of Malibu, Calif., were mauled and eaten in October 2003 by a bear at their campsite, which lay at the confluence of several heavily used bear trails.

Many of the film’s scenes show Treadwell chatting amiably at the camera while sitting just feet from thousand-pound grizzlies, or gingerly touching their noses with his fingers.

“Everything Timothy was doing was wrong, as far as behaving responsibly around wildlife,” said Mike Lapinski, who wrote “Death in the Grizzly Maze,” one of the several books that have been written about Treadwell since his death.

Lapinski called the film “beautiful,” but said he wishes Herzog had put more emphasis on the dangers of approaching grizzlies.

Missy Epping, wilderness district ranger at Katmai, has not seen the final version of the film, but said she was disappointed when she viewed the raw footage shot by Treadwell, particularly the sequences of him touching the bears.

“These are wild animals and we have to remember that,” Epping said. “They are not teddy bears.”

Epping and others confirmed that, since Treadwell’s death, at least a few copycats hoping to gain the same celebrity status as the amateur naturalist have been following bears somewhere on Katmai’s 5 million acres.

And so on. Given that Herzog is famous for pursuing subjects with a romanticism that borders on insanity — in La Soufrière (1977), for example, he took a few cameramen to a volcanic island to interview the one person there who did not evacuate when the authorities thought the mountain might blow — I can totally understand why he, at least, would be drawn to this subject.

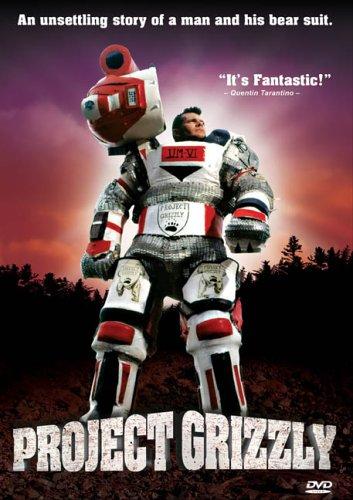

Incidentally, one semi-related film that I really like is Peter Lynch’s Project Grizzly (1996), a hilarious documentary about Troy Hurtubise, a Canadian who became obsessed with getting close to grizzly bears, and thus began to develop the most bear-proof protective suit imaginable. How bear-proof is the suit? Well, he has people beat it with baseball bats, shoot it with rifles, and knock it over with falling logs — sometimes with him standing inside it. The problem is, it’s virtually impossible to move in the suit. And the irony is, by going to such extreme lengths to guarantee his safety, he can never have the intimacy, for lack of a better word, that he seems to want to have with the grizzlies.

Incidentally, one semi-related film that I really like is Peter Lynch’s Project Grizzly (1996), a hilarious documentary about Troy Hurtubise, a Canadian who became obsessed with getting close to grizzly bears, and thus began to develop the most bear-proof protective suit imaginable. How bear-proof is the suit? Well, he has people beat it with baseball bats, shoot it with rifles, and knock it over with falling logs — sometimes with him standing inside it. The problem is, it’s virtually impossible to move in the suit. And the irony is, by going to such extreme lengths to guarantee his safety, he can never have the intimacy, for lack of a better word, that he seems to want to have with the grizzlies.

Feel free to cue Daniel Amos’s ‘Strange Animals‘ here …