I recently watched Cecil B. DeMille’s Samson and Delilah (1949) for the first time in years, and I hope to write something about it soon. But one detail caught my eye, and got me curious to see if it was part of a trend that might have popped up in other Bible movies, too.

I recently watched Cecil B. DeMille’s Samson and Delilah (1949) for the first time in years, and I hope to write something about it soon. But one detail caught my eye, and got me curious to see if it was part of a trend that might have popped up in other Bible movies, too.

Specifically, I was struck by the writing credits that appear during the opening titles. The film gives credit to four different screenwriters, which is fairly typical — no doubt there were other writers who worked on the film without credit, too — but the film also goes on to specify not just that it is based on the Bible, or on a particular book of the Bible, but that it is based on particular chapters within that book.

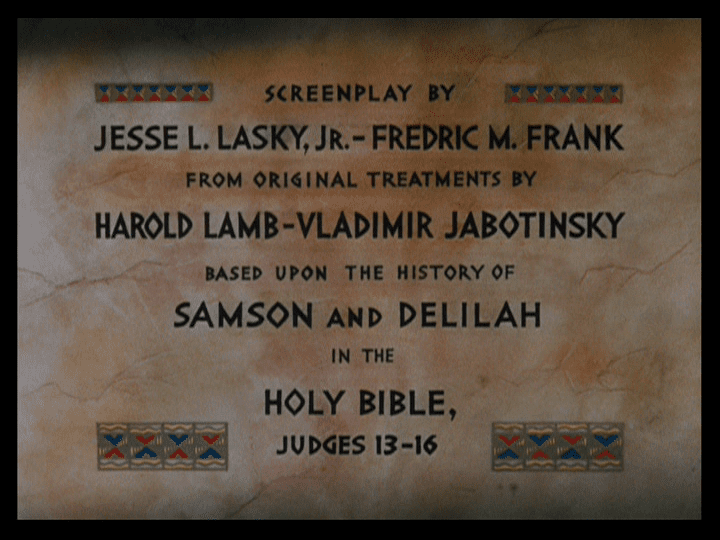

Here are the credits as they appear onscreen:

This got me curious as to whether any other Bible epics had named the specific chapters on which they were based — and after skimming the credits sequences of over a dozen films this morning, I have to say the answer appears, so far, to be no.

But before I get into that, I just have to say it is particularly ironic that Samson and Delilah, of all films, would credit such a narrow portion of the Bible, because the film clearly nods to other parts of the Bible as well, most notably by giving Samson a young sidekick named Saul — who, yes, is identical to the Saul who goes on to become the first king of the Israelites. So that would come from I Samuel, not Judges.

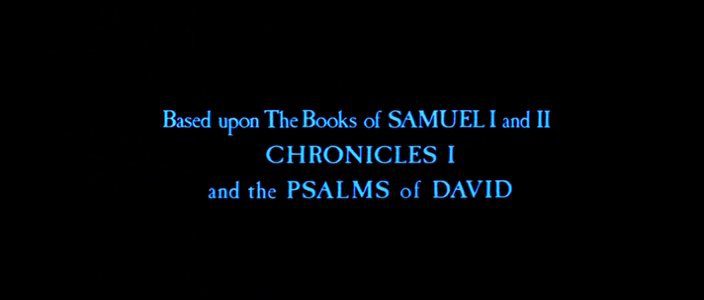

Anyway. When I looked at the credits sequences for all the films that I currently have at my disposal, I focused mainly on mainstream features and did not look at any made-for-TV movies or independent church productions — and I found only one film, King David (1985), that even specified the books it was based on in its credits:

These credits look kind of odd, to me, as they place the numbers of the books after the titles, rather than before. For pretty much my whole life, I have seen “First Chronicles” simplified as “I Chronicles”, not as “Chronicles I” — and the reason is fairly obvious: you don’t want to confuse the number of the book with the chapter numbers that might follow it. So, were the filmmakers drawing on some other tradition that I am unfamiliar with? Or were they approaching the books of the Bible the same way they approach movie sequels, where the number always follows the title?

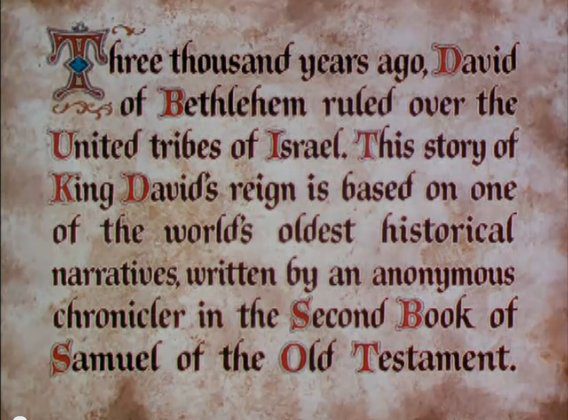

Honourable mention should also go to David and Bathsheba (1951), which does not mention the biblical source material in its credits, per se, but does begin with a couple of title cards that set the story up — one of which mentions “the Second Book of Samuel” and even says the book was written by “an anonymous chronicler”:

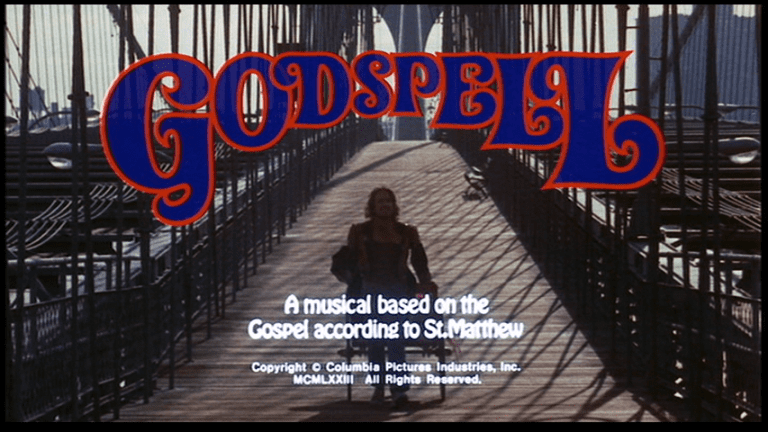

And while it’s not a “Bible epic” per se, I think honourable mention should also go to Godspell (1973), a musical set in the modern era that describes itself on the opening title card as “a musical based on the Gospel according to St. Matthew”:

Note that the attribution here is presented not as part of the credits, per se, but almost as part of the title of the film. And, just as Samson and Delilah made use of more scriptures than the credits let on, so too here: the film says it’s based on Matthew, and it basically is, but it also makes use of parables that are unique to Luke, as well.

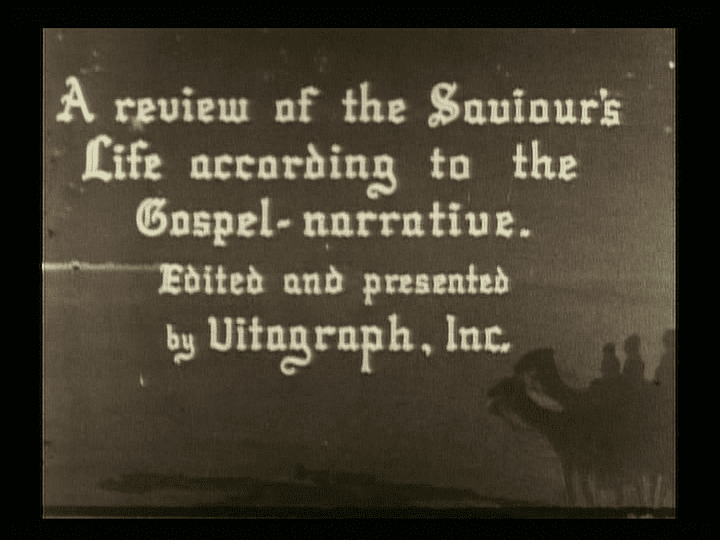

Beyond that, From the Manger to the Cross (1912) makes a general reference to the gospels, but doesn’t mention any of them by name:

And that’s about it. Most films simply credit the screenwriters or, in some cases, the novels that the films were based upon — though at least two films make a very general reference to the Bible in addition to the novels that they credit.

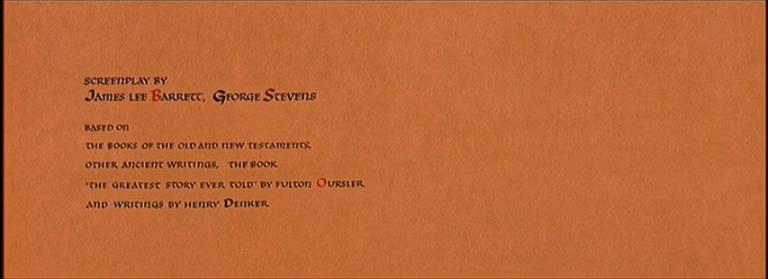

For example, The Greatest Story Ever Told (1965) — which concerns the life of Jesus — states that it is based on both the Old and New Testaments, in addition to other sources, including the novel for which the film was named:

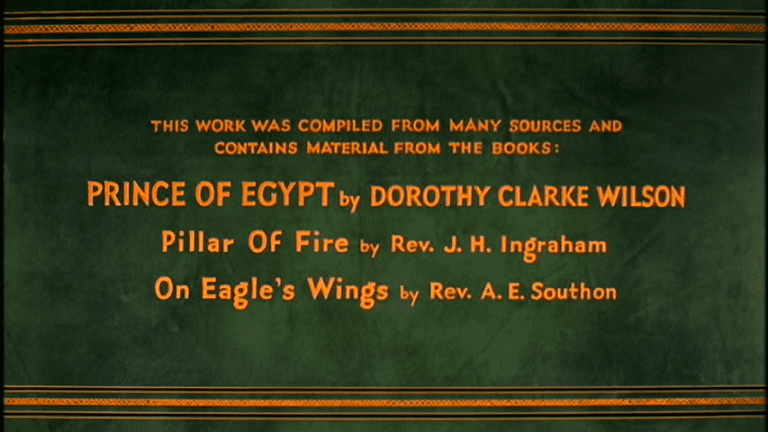

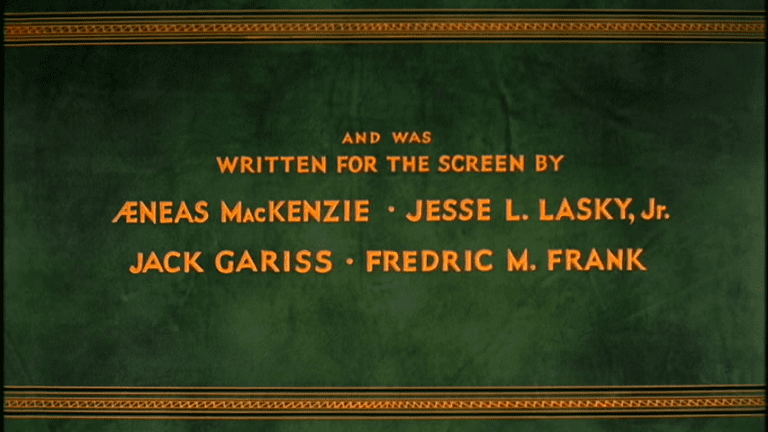

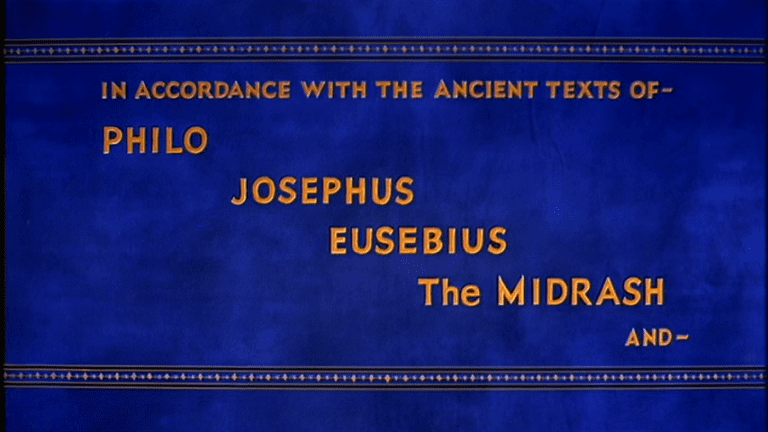

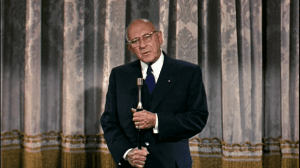

Similarly, DeMille’s remake of The Ten Commandments (1956) devotes an entire title card to the novels it is based on, before crediting the screenwriters:

But then the film does something interesting. The very end of the title sequence, which is where the director’s name normally goes, actually follows DeMille’s name with a reference to the ancient texts he consulted, climaxing with “The Holy Scriptures”:

So DeMille actually gives the Bible the place of honour that would normally have gone to himself. Or, rather, DeMille shares his place of honour with the Bible; just as his name is linked to the scriptures by a sentence that stretches out over the last three title cards, so too his voice begins to narrate the film (“And God said, ‘Let there be light…'”) while the words “The Holy Scriptures” are still onscreen. And so the authoritative voice of one is filtered through the authoritative voice of the other.

Of course, a number of famous “Bible epics” have not been based on the Bible itself but on novels that were, themselves, adaptations of the Bible or fictitious stories that had only a slight connection to the Bible — so the credits for movies like The Robe (1953), based on a novel by Lloyd Douglas, or Ben-Hur (1959), based on a novel by Lew Wallace, didn’t need to credit anything beyond the novels themselves.

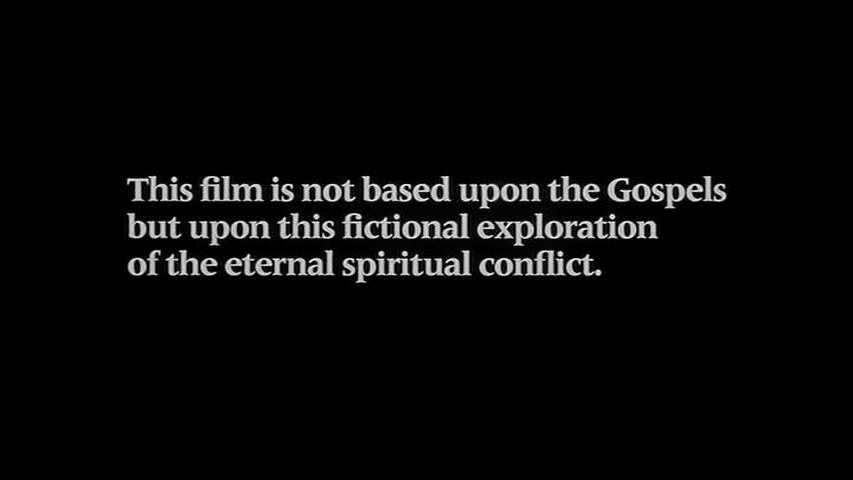

One film, however, famously tried to distance itself from the biblical source material in its opening credits, said film being The Last Temptation of Christ (1988), which was based on a controversial novel by Nikos Kazantzakis:

Finally, one last note on these opening-credits sequences — albeit a note that has nothing to do with how they credit their sources.

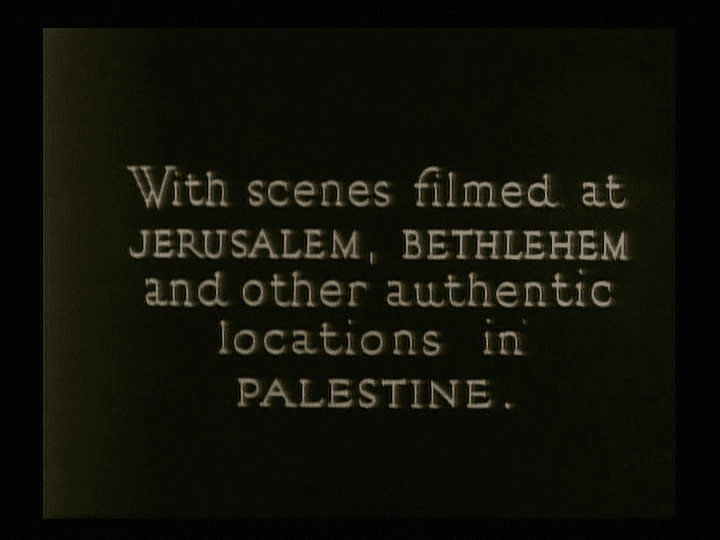

You might have noticed that the credits for The Ten Commandments specify that the film was shot partly in Egypt, and that it will take the viewer on “a pilgrimage over the very ground that Moses trod more than 3,000 years ago”. While a number of Jesus movies have been shot in Israel and have played this up in their publicity campaigns, I can think of only one other Bible film that has emphasized its function as a virtual pilgrimage in the credits, said film being From the Manger to the Cross:

And that about covers it, for now. If I have missed anything, please let me know!

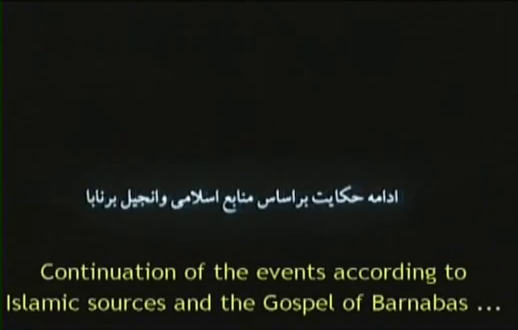

June 22 update: Jesus, the Spirit of God (2007), an Iranian film that tells the Muslim version of the story of Jesus, shows both the Christian and Muslim versions of the crucifixion and introduces each section with a title card, one of which specifies that the Muslim section takes some of its details from the Gospel of Barnabas, a document that seems to have been written in the 14th or 15th century:

The film also concludes with a quote from the Koran, but I’m not sure whether the specific verses cited here are mentioned in the narration — and are thus part of the film proper — or were simply added to the English subtitles:

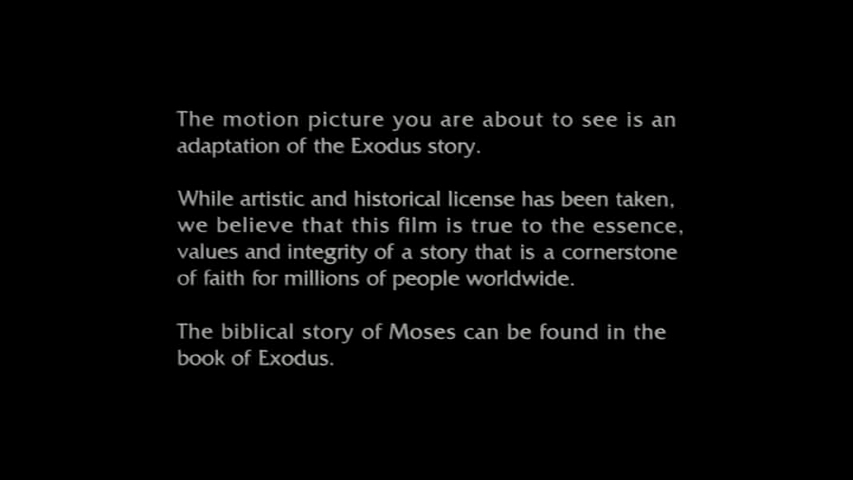

October 27 update: Watching The Prince of Egypt (1998) with my kids the other day, I was reminded that this film, too, begins with a title card that names a particular book in the Bible — in this case, Exodus — as its primary source:

And then, at the very end of the film — after the credits have finished rolling — the film quotes specific passages from the Jewish, Christian and Muslim scriptures to demonstrate that Moses is a prophet revered by three different religions. The biblical passages cited in this title card are Deuteronomy 34:10 and Acts 7:35: