Christians aren’t the only ones who hold Jesus in high esteem. Muslims do too, though they have radically different beliefs about him — and at least one movie has actually tried to dramatize those beliefs the same way other Bible movies have dramatized their own filmmakers’ beliefs.

Christians aren’t the only ones who hold Jesus in high esteem. Muslims do too, though they have radically different beliefs about him — and at least one movie has actually tried to dramatize those beliefs the same way other Bible movies have dramatized their own filmmakers’ beliefs.

But wait… is it right to call Jesus, the Spirit of God, an Iranian film produced in 2007, a “Bible movie”? Is not much of the film based on the Koran and other post-biblical sources, such as the late-medieval document known as the Gospel of Barnabas, rather than on the Bible itself?

Well, yes, the film is based on those other documents, but I’d still say it counts as a “Bible movie” on some level, inasmuch as many of its narrative elements can be traced back through those sources to the Bible itself. If we can accept Ben-Hur, which was based on a novel, or The Passion of the Christ, which was based on the visions of a 19th-century nun, as “Bible movies” because they contain elements that go back to the scriptures, then we can certainly put this film under the same broad umbrella.

I first became aware of Jesus, the Spirit of God several years ago, when it was known as The Messiah, and I wrote several blog posts linking to clips from the film and interviews with director Nader Talebzadeh. But it wasn’t until recently that I finally got around to watching a feature-length version of the film itself.

I say a feature-length version of the film because there are at least two different versions out there, and possibly more. I found two copies of the film on YouTube — you can see one of them to the right — that both came to about 83 minutes. But the stories I linked to in my earlier blog posts indicated that the film should be about 100 minutes, and Wikipedia says the film ought to be over two hours; and that’s before we take into account the fact that the film was cut down from an even longer TV series.

In any case, the 83-minute version is the one I found on YouTube, and there’s quite a bit to talk about just there. So let’s get started. Here’s what struck me on my first viewing of the film.

A Muslim take on Jesus. I don’t know enough about Muslim views of Jesus to say how much of this film reflects core Muslim beliefs, and how much of it reflects uniquely Shi’ite beliefs, and so on, but it’s still possible to spot some pretty obvious ways in which this film’s version of Jesus conforms to Muslim belief rather than Christian belief.

For starters, the Jesus of this film repeatedly and insistently denies that he is divine. So, if the Jesus of this film isn’t claiming to be the Son of God, why do the Jewish leaders want to kill him? (And like it or not, it is definitely the Jewish leaders, more than the Romans, who want to see Jesus dead here.)

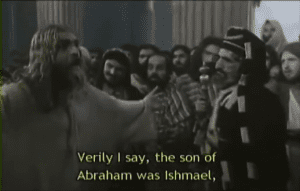

If I’m reading this correctly, they want to kill him because he proclaims the Muslim belief that Abraham put Ishmael, rather than Isaac, on the altar at God’s behest, and because he prophesies the coming of another prophet, i.e. Mohammed, who will correct everyone’s misperceptions about him and his teachings.

If I’m reading this correctly, they want to kill him because he proclaims the Muslim belief that Abraham put Ishmael, rather than Isaac, on the altar at God’s behest, and because he prophesies the coming of another prophet, i.e. Mohammed, who will correct everyone’s misperceptions about him and his teachings.

The film also denies that Jesus was crucified. Instead, Jesus is taken up into heaven by the angel Gabriel, just before the soldiers come to arrest him, and the traitor Judas is physically transformed so that he resembles Jesus and is crucified in his place. (Kudos to the actor, by the way, whose performance as the fake Jesus is noticeably different than his performance as the real Jesus. You really do buy that he is playing two different characters.)

John’s gospel, inverted. Of the four canonical gospels, John’s is the most emphatic about the divinity of Jesus; that is partly why, in Orthodox Christian circles, the author of that gospel is known as St John the Theologian. So it’s striking to see just how much of this divinity-denying film can be traced back to John’s gospel.

Many of the arguments that Jesus has with the other Jews seem to be borrowed from the arguments recounted in John’s gospel. But note also Jesus’ conversation with Nicodemus, the encounter with the woman accused of adultery, the raising of Lazarus, the way Judas objects to Mary pouring oil on Jesus’ feet, and so on.

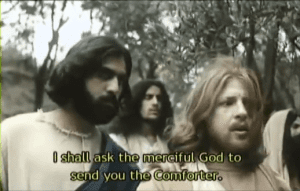

Most amazing, to me, is how, when Jesus promises his disciples that God will send them a “Comforter”, he is apparently referring now not to the Holy Spirit, as Jesus did in John’s gospel, but to Mohammed, the one who, as the Jesus of this film puts it, “will remind everyone of what I have taught and will bear testimony to the truth of my teachings when it has gone astray.”

Most amazing, to me, is how, when Jesus promises his disciples that God will send them a “Comforter”, he is apparently referring now not to the Holy Spirit, as Jesus did in John’s gospel, but to Mohammed, the one who, as the Jesus of this film puts it, “will remind everyone of what I have taught and will bear testimony to the truth of my teachings when it has gone astray.”

No scandal here. Much of the film seems to be designed to eliminate some of the more potentially scandalous elements in the gospels. Chief among these, of course, are Jesus’ claims to divinity, which are not only kept out of this film, but are flipped around so that Jesus now actively denies being divine.

And then, of course, there is the film’s assertion that God would not have allowed Jesus to be arrested, scourged and “forsaken” on the cross. Where Christian theology has always taught that the resurrection of Jesus conquered death in all its forms precisely because he had first suffered one of the worst deaths imaginable, this film reflects the Muslim view that Jesus would never have been subjected to such a thing in the first place.

But there are other striking changes, too. For example, when Jesus is asked whether it is lawful to stone the woman caught in adultery, the film hints strongly that she has been falsely accused, and that Jesus is not actually forgiving her but saving her from the lies of the mob. The implication is that, if Jesus had forgiven her, then he would have been breaking the laws of Moses — which is something he said he wouldn’t do (cf. Matthew 5) — so apparently we can’t have that.

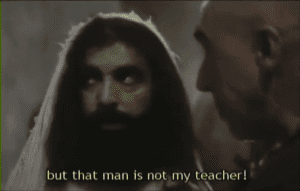

Later, when the fake Jesus is being tried before the authorities, someone accuses Peter of being one of Jesus’ followers — and Peter’s denial now comes across not as an act of cowardice or lack of faithfulness, but as a sign that Peter knows the person being tried before the authorities is not the real Jesus after all.

Later, when the fake Jesus is being tried before the authorities, someone accuses Peter of being one of Jesus’ followers — and Peter’s denial now comes across not as an act of cowardice or lack of faithfulness, but as a sign that Peter knows the person being tried before the authorities is not the real Jesus after all.

Attention to women. It is striking how the miracles Jesus performs are all done for the benefit of women — either directly, in the case of the deaf-mute and the hunchback, or indirectly, in the case of the women whose sons and brothers are raised from the dead. (Before raising Lazarus, Jesus specifically asks God to hear the mourning of the women, which is a detail not found in the prayer he gives in John 11.) There is also a verbal reference to Mary Magdalene being cleansed of evil spirits.

The resurrections, at least, are depicted here more or less as they appear in the Bible, and the bit about Mary’s evil spirits is straight out of the Bible, too. But the biblical deaf-mute was a man, and I know of no biblical precedent for the hunchback — unless there was a translation error in the subtitles.

In addition to the miracles, note also the aforementioned scene in which Jesus comes to the defense of the woman accused of adultery, as well as the scene in which Mary pours oil on Jesus’ feet — and note how, in both cases, there seems to be some merging of identities.

First, the woman accused of adultery says she came from Samaria to look for her husband, which almost sounds like a nod to the Samaritan woman Jesus met in John 4.

First, the woman accused of adultery says she came from Samaria to look for her husband, which almost sounds like a nod to the Samaritan woman Jesus met in John 4.

And second, the Mary who pours oil on Jesus’ feet is identified in the subtitles as Mary Magdalene, which would seem to suggest that the film is confusing the story about Mary of Bethany in John 12 with the story about the anonymous sinful woman in Luke 7, who is often identified with Mary Magdalene in the Western churches — but again, I wonder if there was a translation error in the subtitles.

Characters from Acts. Within the New Testament, there are quite a few characters who appear only in the gospels or only in the Book of Acts, but the events depicted in the gospels flow quite seamlessly into the events depicted in Acts, so I have often wondered what the characters who appear in one source were up to during the events depicted in the other source — and I am always intrigued whenever a film decides to explore that question.

Jesus, the Spirit of God, which takes place entirely within the timeframe of the gospels, introduces at least three characters whose only canonical appearances are in the Book of Acts: Gamaliel, Barnabas and Paul.

Gamaliel basically says and does here what he says and does in Acts: he advises his fellow Jewish leaders to leave the Jesus movement alone, lest they find themselves opposing God.

Gamaliel basically says and does here what he says and does in Acts: he advises his fellow Jewish leaders to leave the Jesus movement alone, lest they find themselves opposing God.

Barnabas, meanwhile, is introduced as one of the twelve apostles, and is described by the narrator as “Joseph the Levite, known as Barnabas, whose affection for Jesus brought him from Cyprus to Palestine.” Most of the details given in that sentence do indeed come from Acts 4, but there are no biblical references to Barnabas during the ministry of Jesus itself.

That being said, later Christian tradition does state that Barnabas was one of the seventy (or seventy-two) apostles sent out by Jesus in Luke 10, so as far as Christian tradition is concerned, there is certainly room to depict Barnabas within the ministry of Jesus on some level — but he was definitely not one of “the Twelve”.

I’m guessing that Barnabas is grouped with the Twelve here because of some tradition tied to the pseudepigraphal Gospel of Barnabas, which is one of this film’s main sources. But as I haven’t read that text yet, that’s just a guess on my part.

Finally, there is Paul — or “Sha’ool”, as he is called here, which I take to be a variation of Paul’s Hebrew name Saul. Paul is introduced as a Roman citizen and as “one of the smartest Pharisees’ students” — we are told that he awes people with his “lectures” — and he is hired by the Jewish leaders to kill Lazarus.

Finally, there is Paul — or “Sha’ool”, as he is called here, which I take to be a variation of Paul’s Hebrew name Saul. Paul is introduced as a Roman citizen and as “one of the smartest Pharisees’ students” — we are told that he awes people with his “lectures” — and he is hired by the Jewish leaders to kill Lazarus.

This is remarkable on a number of levels. For one thing, it brings together the plot against Lazarus mentioned in John’s gospel (which never tells us whether the plot was successful, incidentally) and Paul’s murderous campaign against the early Christians as described in Acts. But it also brings to mind The Last Temptation of Christ (1988), which also showed Paul killing Lazarus after his resurrection.

Relationship to violence. Violence plays a very different role in Islam than it does in Christianity: whereas Jesus told his followers to turn the other cheek and allowed the Romans to kill him, Mohammed led military campaigns against his enemies.

Not coincidentally, the key scriptures in both religions also have profoundly different attitudes towards the relationship between church and state (or mosque and state, as it were): It has sometimes been observed that the New Testament was written with the assumption that Christianity would always be a minority faith — which has led to complications when Christianity became the faith of emperors and presidents and the soldiers who follow them — whereas the Koran specifies how Muslims ought to rule the societies they assimilate.

That alone would make Jesus, the Spirit of God’s approach to these issues kind of fascinating. But when you add the fact that this film was produced with the approval of the Iranian government — a theocracy that can trace its roots to a revolution that took place less than 30 years before this film was made — it becomes even more interesting.

So, right at the beginning, the film establishes that Judea has been colonized by invaders, namely the Roman Empire. What resonance would this have, I wonder, for audience members who can still remember living under the Shah, who was supported by the U.S.? Then the film establishes that Barabbas is one of the Zealots who urge their fellow Jews to throw stones at the Romans like David did against Goliath. How would a line or a scene like this play, I wonder, to Middle Eastern audiences who have seen images on TV of, say, Palestinians throwing rocks at Israelis?

So, right at the beginning, the film establishes that Judea has been colonized by invaders, namely the Roman Empire. What resonance would this have, I wonder, for audience members who can still remember living under the Shah, who was supported by the U.S.? Then the film establishes that Barabbas is one of the Zealots who urge their fellow Jews to throw stones at the Romans like David did against Goliath. How would a line or a scene like this play, I wonder, to Middle Eastern audiences who have seen images on TV of, say, Palestinians throwing rocks at Israelis?

Matters are intensified later on when a Roman soldier witnesses one of Jesus’ miracles and declares that Jesus is “the son of God” — echoing, perhaps, the passage in Mark 15 where a Roman centurion says something similar after Jesus’ death — and this declaration prompts Barabbas and the other Zealots to declare that “whoever says Jesus is God or son of God must be killed.” A Muslim audience would presumably agree with Barabbas that Jesus is not divine — but would they agree with his call to arms over this issue?

Matters are complicated even further by another scene in which one of the Jewish leaders tries to persuade Barabbas that Jesus is their common enemy. Given that the film, in later scenes, will go to great lengths to suggest that the Jews, rather than Pilate, are responsible for the death of the fake Jesus (i.e., the film says “the cruel hearts of the Children of Israel” are so determined to kill Jesus that they cannot even tell when they are calling for the death of the wrong guy), you cannot help but wonder if Barabbas is supposed to be viewed through this anti-Semitic lens, too.

(Incidentally, the scene between the Jewish leader and Barabbas could not help but bring Monty Python’s Life of Brian to mind. The leader says they have a common enemy. Barabbas says yes, it is Rome. The leader tells Barabbas to think harder. Barabbas replies, you mean Jesus? I half-expected him to say, “The Judean People’s Front!?”)

(Incidentally, the scene between the Jewish leader and Barabbas could not help but bring Monty Python’s Life of Brian to mind. The leader says they have a common enemy. Barabbas says yes, it is Rome. The leader tells Barabbas to think harder. Barabbas replies, you mean Jesus? I half-expected him to say, “The Judean People’s Front!?”)

Extra miracles. There are at least three miracles in this film that have no direct parallel in the gospels whatsoever, though they do touch on themes that are already present in the gospels in some way.

First, the disciples ask if God will send manna from heaven, and lo, after Jesus kneels and prays, a meal complete with dishes and a tablecloth (if not an actual table) appears on the ground before them. Judas, however, won’t eat any of the food because he believes it’s nothing but a mirage — and it is suggested that it was because of his disbelief that Judas was eventually crucified in Jesus’ place.

There is no equivalent episode in the New Testament, but the question of manna and divine gifts of food does come up in a few places, in ways that sort of fit this episode but also sort of don’t.

For example, during his temptation in the wilderness, Jesus refuses to turn the stones to bread. But then, during his ministry, he feeds entire crowds with just a few loaves of bread: the feeding of the five thousand is the only miracle that appears in all four gospels, and in two of those gospels, the miracle sort of happens twice, since Mark and Matthew also report a separate incident in which Jesus fed four thousand people.

For example, during his temptation in the wilderness, Jesus refuses to turn the stones to bread. But then, during his ministry, he feeds entire crowds with just a few loaves of bread: the feeding of the five thousand is the only miracle that appears in all four gospels, and in two of those gospels, the miracle sort of happens twice, since Mark and Matthew also report a separate incident in which Jesus fed four thousand people.

What’s more, in John’s gospel, the feeding of the five thousand is followed by a heated exchange between Jesus and his fellow Jews, in which Jesus compares and contrasts the manna that God gave the Israelites under Moses with the eucharistic bread that will allow people to eat Jesus’ own flesh.

So, the New Testament does allow for miraculous supplies of food — but the miracles it does report are very public, and involve thousands of people, rather than the private miracle which the film shows taking place between Jesus and his disciples only.

Another “extra” miracle in this film comes when Jesus defends the woman who has been accused of adultery.

In the biblical version of the story, it says that Jesus “bent down and started to write on the ground with his finger” when the woman was brought before him. The Bible doesn’t say what, exactly, Jesus wrote, and many of the films that have included this detail haven’t really elaborated on it. But occasionally, films like Cecil B. DeMille’s The King of Kings (1927) have expanded on this detail, by having Jesus write down the names of specific sins that the woman’s accusers may have committed. Films like these suggest that the woman’s accusers refrained from stoning her in the end because Jesus revealed their secret sins.

In the biblical version of the story, it says that Jesus “bent down and started to write on the ground with his finger” when the woman was brought before him. The Bible doesn’t say what, exactly, Jesus wrote, and many of the films that have included this detail haven’t really elaborated on it. But occasionally, films like Cecil B. DeMille’s The King of Kings (1927) have expanded on this detail, by having Jesus write down the names of specific sins that the woman’s accusers may have committed. Films like these suggest that the woman’s accusers refrained from stoning her in the end because Jesus revealed their secret sins.

Jesus, the Spirit of God goes even further, though, by having Jesus create a sort of pool in the sand that acts as a mirror of sorts, so that when one of the accusers looks into the pool, he sees a hideous, ghostly, demonic version of his face instead.

Finally, I am also struck by the scene in which the Jews try to stone Jesus, and Jesus walks through them like he’s invisible. The gospels do include scenes in which crowds try to kill Jesus and he somehow gets away, but his escape is never made as explicitly supernatural as it is here. Nor do the gospels go as far as this movie does, in suggesting that the Jews stoned each other to death in their efforts to kill Jesus.

![]() Odds and ends. Just before the soldiers come to arrest Jesus, the film throws a title card up on the screen that says: “Continuation of the events according to the Christian narrative.” Then, after compressing the traditional Passion narrative to about four minutes, the film throws another title card up on the screen that says: “Continuation of the events according to Islamic sources and the Gospel of Barnabas.” And so the rest of the film depicts the Muslim belief that Judas was crucified in Jesus’ place.

Odds and ends. Just before the soldiers come to arrest Jesus, the film throws a title card up on the screen that says: “Continuation of the events according to the Christian narrative.” Then, after compressing the traditional Passion narrative to about four minutes, the film throws another title card up on the screen that says: “Continuation of the events according to Islamic sources and the Gospel of Barnabas.” And so the rest of the film depicts the Muslim belief that Judas was crucified in Jesus’ place.

I find it puzzling that the film felt the need to actually show the Christian version of the story before offering its own version of those events. By this point, the film has already deviated from the Christian version of the story in countless other ways, so why suddenly draw our attention to the differences between the two traditions now? Why not just let the film proceed with its own version?

Finally, I cannot help but notice that the almost-final image of Jesus in heaven has him looking a little older, and that he is now wearing blue over red in that shot — just as he does in traditional Christian icons. The irony is, in Christian iconography, the red and blue signify the two natures of Christ — his divinity and his humanity — but presumably this film didn’t mean to suggest anything along those lines.