Life got crazy busy around the time Exodus: Gods and Kings came out, and frankly I found the movie itself kind of dispiriting, so I haven’t been as up-to-date with the links and things as I would have liked to have been. But I hope to do a bit of catching up in the next little while, before the film fades entirely from view.

Life got crazy busy around the time Exodus: Gods and Kings came out, and frankly I found the movie itself kind of dispiriting, so I haven’t been as up-to-date with the links and things as I would have liked to have been. But I hope to do a bit of catching up in the next little while, before the film fades entirely from view.

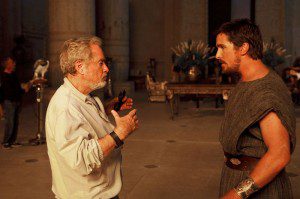

First up, some links to the interviews that director Ridley Scott and co-stars Christian Bale and Joel Edgerton did with the “faith-based” media. Exodus may be the first major Bible production since The Passion of the Christ for which I wasn’t able to snag an interview myself, but a few of my colleagues got to speak to the filmmakers after the film’s New York premiere.

First, Steven D. Greydanus of the National Catholic Register, who has written quite a bit lately about atheist directors tackling religious subjects, asked Ridley Scott if being a non-believer himself gave him any advantages or handicaps, and Scott made an interesting comparison with science fiction, which he wasn’t much of a fan of either before he made his name with Alien and Blade Runner:

Scott: I think it helps. The shallow parallel is that I never liked science fiction as a child, until Stanley [Kubrick] did 2001. Then I thought, “Aha. Here’s the threshold; here’s the doorway.” [Then I saw] Star Wars, which was seminal — a milestone; those two science fictions [movies] are head and shoulders above anything else. So, thereafter, I was converted, and I knew how to do a science fiction [film]. And, lo and behold, I was offered this pretty savage thing called Alien, and away you go. . . .

I made the mistake of saying I was an atheist at one point, when I was doing Kingdom of Heaven. The writer I chose to polish [the Kingdom of Heaven screenplay] said you couldn’t have asked a worse person to do it, because [he was] a dyed-in-the-wool atheist. And I said, on the contrary, it’s a bit like science fiction: Because I never believed in it, I had to convince myself every step of the way what made sense and what didn’t make sense, what I could reject and accept . . .

Jonathan Merritt at the Religion News Service offers his own version of the round table interview, which overlaps somewhat with Greydanus’s account:

Q: Why did you use a child for the figure of God?

Ridley Scott: Not figure of God. “Malak” means messenger. So “Malak,” to begin with, is the messenger of God. If you’re going to represent God in many shapes and forms, which He will appear, the biggest form of all is probably nature. That’s his power, that’s his base, that’s his beauty, that’s his threat. And occasionally when you want to communicate with someone, it’s very easy with His power to chose a messenger. Or some more popular word might be “angel.” But I didn’t like the idea of an angel associated with wings. I wanted everything to be reality based….

If you’re watching very closely you notice that whenever [Moses and Malak] are witnessed from a distance–Joshua does a lot of sneaking up over rocks and looking to see what’s going on–he can’t see anything. [Joshua] just thinks his leader has lost his mind ’cause he can’t see anything. When you’re in close you can see who Moses is talking to. Of course, when you think of it horizontally or vertically, whichever is the best way, [Moses] also could be talking to his conscience. So Malak could also be his conscience.

Alissa Wilkinson at Christianity Today spoke to Bale and Edgerton about the personal dynamic between the two main characters:

I’m really intrigued by the family dynamic of the story. The whole movie was set up as being about choosing your family, or being rejected by family. There’s a really big emphasis on the question: “Are these your people, or not?” There’s the death of the firstborn sons, and of course there’s the brotherly relationship. This all feels really close to what the story of Exodus is about, which is God choosing his people and leading them out of slavery. How much did this come up for you as you were preparing for your roles in the film?

Bale: Very much. I think it helped us find an ending for the film. The five books of Moses just keep going and are fascinating. Some of the earliest conversations I would have with Ridley would be me calling him up and saying, How can you not have this section in it? How can you not have the prayer of Miriam? And how can you not . . . Because everything seems to become essential.

Then you realize you can’t make an eight hour long film.

So it became, well, if we really focus on this brotherly bond—which is a fascinating bond: two men who are cynical about this pat theology of the Egyptian gods, who view it as a means to prop up the Pharaoh and have the citizens worship their leader. One is exiled and experiences purification in the desert and has a family and then is compelled by God; the other comes once he’s in power to have all of the arrogance of power and also the trivial nature of someone desperately holding on to power. He starts to believe the hype, starts to believe that he is a god, and then there’s that ensuing confrontation. That was such a complete relationship in and of itself, and it gave us right around a two-hour long film. So [that family story] ended up being perfect.

Then I just had to put up—well, no, rather Ridley just had to put up with me constantly saying Yeah, but, there’s all this other great stuff; Yeah, but, Rid, have you read this bit, I’m going to send you this passage now. And he’s like, Yeah, that’s great, Christian, I mean, I can’t film everything.

Regarding that line about Moses and Ramses both being cynical at the start of the movie and then having diametrically opposed beliefs about deity by the time they meet each other again, Bale made a similar point in a Q&A after a BAFTA screening last week, where he said that Moses and Ramses both start out as “atheists”:

Turning to other “faith-based” media, Scott told Emma Koonse of The Christian Post that the voice of God heard by Moses could have awoken his conscience:

“Conscience, the power of conscience can unearth all kinds of things,” Scott said before noting that the number of slaves in Egypt during Moses’ period are indeterminate, but that Exodus features 400,000 slaves.

“In some ways I cannot believe that any clear thinking, normal-minded person could not have second thoughts about what is perceived as status quo, which was fundamentally slave labor,” Scott added.

He also addressed the fact that the movie does so little with its female characters:

As a result of the film’s emphasis on Rhamses and Moses, Scott deviated from the norm of having strong female characters as lead roles. Characters such as Moses’ sister, Miriam, and his wife, Sefora, were present in “Exodus: Gods and Kings,” but were not explored in-depth.

“At the end of the day the way the script was set up, it wasn’t really about that,” Scott said, referring to the female characters. “There was no need for more, it was about the evolution of Moses in relation to his relationship with, if you like, his brother, Rameses. As much as we tried to give more stuff to various characters, it didn’t really make sense.”

Finally, Deadline ran an article on the challenges of marketing the film for religious audiences, and focused partly on the work of Different Drummer:

But not all Christians will have a problem with this, according to Marshall Mitchell, who co-founded faith-based entertainment marketing firm Different Drummer, which handled the religious outreach for Fox on Exodus. “There’s not one homogeneous evangelical crowd, so people are going to be all over the place (with their opinions). For a lot of Christian audiences, Exodus is another stop along the journey of religious discovery and faith engagement. Exodus isn’t expected to define their (Christian) faith, but it’s a tool that they will agree with strongly or disagree with strongly.”

Mitchell points out that even Cecil B. DeMille’s 1956 classic The Ten Commandments took liberties with the Old Testament, filling in narrative gaps, and that film hasn’t suffered over time from the religious establishment.

“I think people are going to approach Exodus individually, taking a piece of Moses that resonates with them.”

Different Drummer implemented numerous forms of outreach to drum up awareness for Exodus, including playing the trailer at several Christian conferences over the past two months, inviting a number of Jewish, Muslim and Christian leaders from various sects to a 40-minute sizzle reel of the film in select cities as well as advance screenings. The lobby of the American Bible Society’s HQ in New York is adorned with Exodus ads. TV spots for Exodus were bought specifically during NFL events, given the sports crowd’s Christian sensibility. Rev. Floyd Flake of New York’s Greater Allen A.M.E. Cathedral, which counts 30,000 members, even publicly extolled Exodus.

If I find any more “faith-based” interviews, I will add them to this post.