Alissa Wilkinson has an article in The Atlantic under the headline ‘Can Indie Filmmakers Save Religious Cinema?’ It’s a question that I and others have been asking for at least 20 years, and I imagine other Christian film writers were asking it even earlier (going back at least to 1981’s Chariots of Fire, which was distributed by Warner in North America and by Fox overseas but was produced independently).

What jumps out at me, though — given my interest in Bible films — is this bit (links and boldface added):

One of the featured events at Sundance this year was a panel on faith-based films. Several attendees I spoke with were disappointed that panelists focused predominately, once again, on the “faith and family” audience—the same underlying market confusion I’d observed all year. One attendee, Ryan Daniel Dobson, is a Christian filmmaker developing a project based on the Biblical story of Hosea, in which the prophet is told by God to marry a prostitute, who repeatedly abandons him. A project like this will likely interest many people of faith, but not those looking for a “family film.” Like a growing number of Christians who work outside both the Hollywood system and the Christian film industry, Dobson sees films like God’s Not Dead as nearly antithetical to his understanding of what film ought to do and what faith ought to look like.

“Several times ‘faith films’ were compared to superhero movies, where a studio can’t stray from what their fanboy audience wants, because it would guarantee a box office fail.” Dobson told me. “Several times, it was said, ‘We’re doing this for them’—the audience. I find that particularly heartbreaking when said on the grounds of a festival where stories are told with such honesty that it forces the audience to admit they might be wrong.”

Hosea, to my knowledge, has been virtually ignored by filmmakers for most of the medium’s history (the only thing that comes to mind is a reference to him in The Green Pastures, a 1936 film that reimagines stories from the Old Testament in a sort of African-American folk idiom, but even there, he is never depicted), but in recent years there seems to have been a growing interest in him and his story.

First there was the short film Oversold (2008), a modernized version of the story which starred former porn star Crissy Moran as a Vegas stripper who falls in love with a pastor. (The pastor is named Joshua, which may be a nod to the fact that the biblical Joshua’s original name was also Hosea — or, as it is often spelled, Hoshea.)

That film is available for rent or purchase through Amazon, and I highly recommend my friend Matt Page’s review of it. You can also see a trailer for it here:

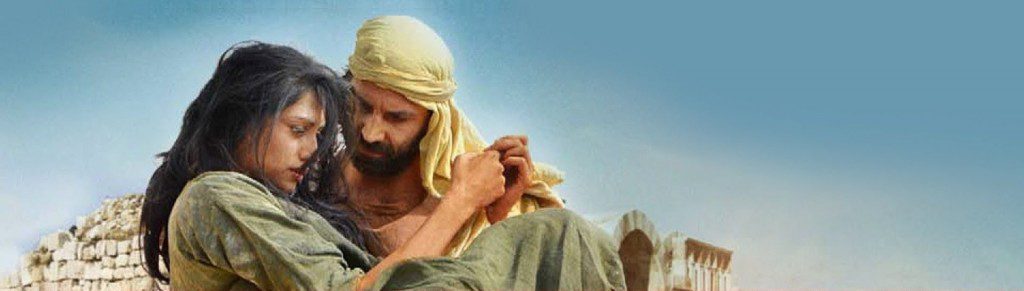

And then there was the feature film Amazing Love (2012), which stars Sean Astin (in his first Christian movie, before Moms’ Night Out and Do You Believe?) as a pastor who tells the story of Hosea and Gomer to his youth group while the story itself is shown to us in flashbacks. You can see a trailer for that one here:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=C9tkZOWPAwU

Interestingly, both of these films encourage a sympathy for the Gomer character that is not mandated by the text and is sometimes missing from interpretations of it.

In Amazing Love, Gomer has legitimate concerns about the way Hosea’s preaching hinders his efforts to earn a living. She also complains that their children are being teased because of the bleak, prophetic names Hosea has given them, and she suggests that people might be more willing to turn to God if God was “not so judgmental.”

Similarly, Oversold encourages sympathy for its Gomer character, here named Sophi, by showing how her boss threatens her and coerces her into continuing as a stripper and possibly even working in pornography. Meanwhile, Joshua loses his job when members of his church object to his marriage to Sophi (in a scene that was reportedly inspired by objections the filmmakers faced when Moran was cast in the role).

Both films use framing devices that draw attention to how the films differ from the biblical story: in Amazing Love, the pastor tells the teenagers that he is expanding the narrative so that his audience “can get a little more appreciation for the facts,” while the narrator in Oversold acknowledges that the biblical story is a lot messier than the film, because Hosea and Gomer had children, which Joshua and Sophi do not.

Both films also draw explicit links between Hosea and Jesus. Oversold begins with a scene in which Joshua preaches not from Hosea directly, but from a passage in Matthew 9 in which Jesus quotes Hosea. Amazing Love, for its part, notes how Hosea gave up everything to redeem Gomer, and how Jesus gave up all that he had by dying on the cross; the film also encourages teenagers to love each other rather than judge each other — or, as the pastor puts it, “Jesus, in you, could love a Gomer.”

So, it will be interesting to see how Dobson’s film compares to these other two.

One last bit of trivia: Astin’s wife in Amazing Love is played by Erin Bethea, who played Kirk Cameron’s wife in Fireproof. And Astin played Cameron’s best friend in the 1987 body-switching comedy Like Father, Like Son, with Dudley Moore.

It’s all connected, I tell you. It’s all connected.