It’s a hot Tuesday morning in late October on the outskirts of Ouarzazate, a city in the heart of Morocco, and Jesus is having trouble getting birds to fly.

More specifically, an actor playing Jesus is having trouble. He’s standing in a replica of the Jerusalem temple, and he’s shooting the scene in which Jesus turns over the tables and scatters the animals that Jewish pilgrims are being pressured to buy for their sacrifices.

In take after take, the actor — Haaz Sleiman, best known perhaps for playing an illegal immigrant in Tom McCarthy’s The Visitor — flips the tables while the followers of Jesus chant, “Down with the moneylenders!” Every time they shoot this sequence, Sleiman grabs a wooden cage full of doves or pigeons, opens it, and turns it on its side to shake the birds free — and every time he does this, most of the birds cling to the cage.

A few do take flight, though they don’t go very far. Instead, they perch on the top of the colonnade and turn to look back down at the temple courtyard. Like the journalists who have come from halfway around the world, the birds want to see how this movie is made.

The movie in question is Killing Jesus, the National Geographic Channel’s adaptation of the best-selling book by Bill O’Reilly and Martin Dugard. (It premieres March 29.)

This is the third film that the channel has based on one of O’Reilly and Dugard’s books — the first two, Killing Lincoln and Killing Kennedy, are the top-rated programs in the channel’s history — but because the subject matter is so different from that of its predecessors, it’s the first in the series that the channel is producing outside of the United States.

The filmmakers came to Morocco partly because one of the producers is Ridley Scott, who has already shot films like Gladiator and Kingdom of Heaven here. But Ouarzazate has also played host to countless Bible-themed productions over the past half-century and then some, going back to 1962’s Sodom and Gomorrah.

This is where Martin Scorsese shot The Last Temptation of Christ in the 1980s. This is where the Emmy-winning ‘Bible Collection’ series of TV-movies was filmed in the 1990s. This is where Mark Burnett and Roma Downey produced their hit miniseries The Bible just a few years ago.

In the lobby at the hotel where this writer is staying, there is a throne left over from a 15-year-old production called The Friends of Jesus: Mary Magdalene.

And every morning, there are call sheets on the desk for CNN’s Finding Jesus (then called The Jesus Code) and NBC’s A.D.: The Bible Continues, both of which are shooting in other studios while Killing Jesus takes advantage of a Jerusalem set that was originally built on a hill in the middle of nowhere for the 1999 CBS miniseries Jesus (the one that starred Jeremy Sisto as Jesus and Gary Oldman as Pontius Pilate).

Some might wonder if all of these productions are beginning to get in each other’s way, but Killing Jesus producer Teri Weinberg, a former NBC executive, says the people working on the various shows have enjoyed spending their downtime together back at the hotel. “So many new friendships have been made,” she says. “The producers on the ground, we’ve all talked about, ‘What challenges are you having?’ We’ve all been really rooting for each other.”

Despite the well-established infrastructure, shooting in Morocco has not exactly been easy. “It’s been very rewarding, shooting in Morocco, but it is quite tough,” says director Chris Menaul. “It’s not hot now, but when we started it was very hot, and a lot of people have gone down with illness. Some of them have come back to us and some haven’t.

“And of course, communication. If we were making the picture in French, it would be a lot easier, because virtually all of them speak French as well as Arabic. But being English, our language is absolutely useless. So we have to use interpreters to do these crowd scenes.

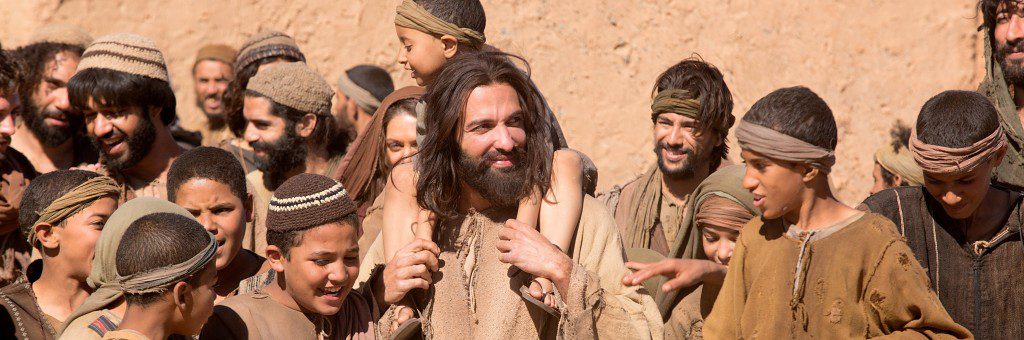

“There are lots of scenes like this where Jesus is working the crowd — that’s what the scene’s about — and that’s difficult when they don’t speak your language and you don’t speak theirs. But we’ve got some great stuff out of the Moroccan crowd. They’ve really got into it, and I think we have achieved that sense of a relationship and a man who did have huge popular appeal.”

Killing Jesus marks a departure of sorts from previous films about Jesus. For one thing, there is the casting: Unlike most English-language films that have cast a blue-eyed northern European in the title role, this film has Sleiman, an actual Middle Easterner who was born in the United Arab Emirates and raised in Lebanon.

Sleiman, who was raised Muslim but now says he’s more “spiritual” than religious, says he feels “very lucky” to have been cast in this role. “It’s kind of surprising that it took so long for someone like me to be cast to play Jesus,” he says.

“One person said, ‘Oh great, maybe people will look at Arabs differently.’ I mean, listen, I’m not saying that’s really the essence of what I’m doing, but how great! If that comes as well, great, let’s add to that. Talk about building bridges.”

The other significant departure from most previous films — and in this, Killing Jesus is following the template set by O’Reilly and Dugard’s book — is that this film aims to focus on the “historical” aspects of the story while staying respectfully agnostic on the question of whether there was anything “miraculous” about the ministry of Jesus.

The film does begin with prophetic dreams and wise men who follow a star to Bethlehem, and it does end with an empty tomb. But there aren’t any resurrection appearances, nor are there any of the more obvious miracles such as walking on water or turning water to wine.

Instead, the film focuses on possible coincidences or on acts of healing that, depending on one’s belief, could have been due to Jesus’ personal charisma as much as to any supernatural force.

“We see him cure a child, who is kind of extremely ill and is fitting and frothing at the mouth,” says Menaul. “He could be suffering from epilepsy, and people get over epileptic fits. Jesus obviously was a very charismatic figure, and in the scene, he embraces him, and he calms him down and talks to him very sympathetically, and the child eventually comes out of that and is cured. And then you see a scene in the marketplace where everybody is saying, ‘It’s a miracle, it’s a miracle.’ Well, maybe it was and maybe it wasn’t.

“The other sort of miracle we see is when he’s out and he’s recruiting his first disciples, and Simon Peter talks about how there have been very poor catches, no fish for ages, and Jesus says, ‘Well, let’s pray,’ and they pray, and then they get a very good catch of fish. Well, it could be miraculous, or it could just have been luck. It’s up to the audience to decide. And I think that’s quite unusual in films about Jesus, letting the audience decide.”

A tour through the film’s costume department — where the chief costume designer illustrates a point by getting this writer to try on Herod’s robes — hints at other ways in which this production might be different from the ones that came before it.

A garment hanging on one of the racks bears a tag that says, “Girl (Jesus’ Sister).” When asked about this, a unit publicist replies that the girl in question is never identified as the sister of Jesus, per se, but is simply one of the children who lives in the same “compound” as Jesus’ family. So she could be a cousin or some similar sort of relative.

Similarly, when it comes time for Sleiman’s Jesus, covered in wounds and a crown of thorns, to carry his crossbeam through the streets of Jerusalem, he is followed by his mother Mary, his followers John and Mary Magdalene, and — in a detail not found in the gospels or in any other film — his brother James.

Very few films have paid any attention to the brothers and sisters of Jesus, who are mentioned briefly in passages like Mark 6:3. Even the book by O’Reilly and Dugard pretty much ignores the siblings of Jesus, save for a footnote that says different churches have different ways of reading these verses, because of the implications for traditional beliefs about the perpetual virginity of Mary.

But the filmmakers say they wanted to focus on Jesus’ family as part of a broader objective, to emphasize his humanity. “What Jesus was trying to do all the time was show us our beauty as humans,” says Sleiman. “His focus was us, humans. So that’s why I’m trying to make him as human as possible, because that’s what he was trying to do.

“I think it translates really nicely,” he adds, “with the connections he has with his mother and with Mary from Magdala and Peter, to see him connect with them like he’s one with them.”

This emphasis on the humanity of the characters extends even to the “villains” of the film: the kings and priests who conspire to kill Jesus, even when he is a newborn.

Kelsey Grammer, for example, plays Herod the Great as a paranoid but deeply troubled man who is haunted by nightmares and turns to the priests — Caiaphas (Rufus Sewell) and his father-in-law Annas (John Rhys-Davies) — to soothe his fears.

Eoin Macken, who plays Herod’s son Antipas, says he was inspired by the “sensitivity” with which Grammer played the aging tyrant, even as Herod — who famously executed two of his own sons — orders the deaths of the children in Bethlehem.

“You kind of understood him,” says Macken. “He was going through pain, and I think that was very important, because there are some moments with the two of us where we don’t particularly like each other, but there’s a connection.”

Grammer concurs. “As actors, you’ve always got to fill in the lines. Bad guys, you’ve still got to humanize them. They still have to get up in the morning and go to the bathroom, and have breakfast, go out and love their children.” He pauses. “Or kill them.”

Rhys-Davies, who is famous for playing Sallah in two of the Indiana Jones films and the dwarf Gimli in The Lord of the Rings, is the only actor who meets with the journalists off the set in full makeup and costume (albeit without some of Annas’s heavier priestly vestments), and he often slips into character when answering a question.

Asked if the priests underestimated Jesus, he replies, “No! Of course we didn’t! Our job is quite simple. Our job is to stop the Jewish people being exterminated by the Romans.”

And that job is made harder, of course, if the Jewish people start following Jesus or any of the other would-be messiahs who keep coming out of Galilee. “Listen, this guy claims that God talks to him,” says Rhys-Davies. “I have been the high priest of Israel, the guardian of the Holy of Holies, all my life. I think I know who God would talk to.”

By all accounts, one of the best scenes in the film may be the Sermon on the Mount, in which Jesus teaches his followers to recite the Lord’s Prayer.

“That was, like, powerful,” says Sleiman. “It was a powerful moment, to just stand there and look at people and not judge. There’s all kinds of people, right? And you don’t know who this person is, where they came from, what they did in their life, what they thought, whatever — and the ability to stand there and give everybody love and not judge? I mean, it doesn’t get any better than that.”

Grammer, whose character dies when Jesus is still an infant, doesn’t share any scenes with Sleiman, but he says he heard good things about that scene too when he first came to Morocco. “A lot of the gals that are producing the show are Jewish, and when I first arrived, they told me, ‘We just shot the Sermon on the Mount scene, and it was so moving.’ And I said, ‘Wow, imagine what it must have been like the first time.’

“It’s part of my culture,” he adds. “I mean, I’m a Christian. So I have a great sense of reverence for all this stuff, but you can’t play that. That people are discovering that it might have been moving is a good thing.”

– – –

Your intrepid reporter, second from the left, on the temple set in Morocco:

– – –

Fun fact

The temple set in Killing Jesus was originally built for the miniseries Jesus, which aired in Europe in 1999 and in North America in 2000.

The set has since been used in a variety of other films, but over the years it began to fall apart; an entire section of the eastern wall had collapsed by the time Killing Jesus came along, and you can still see the rubble and the gap in the wall in this satellite image and in this photo taken from the top of the temple’s steps.

Production designer Tom McCullagh says the set was in a “pretty bad state” when he found it — “Half of it had disappeared or blown down” — but it gave him a head start that he couldn’t find anywhere else. So his team spent six weeks rebuilding the missing walls, using molds that he got from the Italian construction manager who built the set in the first place.

“It was a bit of a jigsaw but it was good,” says McCullagh.

– – –

Fun interviewee

John Rhys-Davies is a natural performer and raconteur.

Sitting by one of the temple walls between takes — on a simple scene in which his character, the high priest Annas, walks up some steps into the temple courtyard with Rufus Sewell’s Caiaphas and Kelsey Grammer’s Herod the Great — Rhys-Davies looks over at the reporters who arrived that morning and asks, “Are these those blasted journalists?”

When someone asks him how long he has been here in Morocco, working on the film, Rhys-Davies replies, with mock weariness, “A lifetime.”

Later, in a lunch tent down the hill from the Jerusalem set, Rhys-Davies shows up for his roundtable interview wearing his false beard and his robes, and as he approaches our table, he looks at a bearded, red-haired member of the group and bellows, “You’ve got a bit of dwarf in you, lad!”

Rhys-Davies has appeared in a number of Bible movies over the years, going back to the 1978 TV-movie The Nativity. When I mention that he played Silas in one of my favorites, the 1981 miniseries Peter and Paul (starring Robert Foxworth and Anthony Hopkins), Rhys-Davies replies, “Oh, many years ago! That was fascinating. We shot that in Greece. You really understand how astonishing Paul is…”

And then, much to my surprise, he proceeds to talk about the rise of the early Church and the foundations of western civilization for a solid, uninterrupted eleven minutes.

More recently, he played the high priest Caiaphas in last year’s Saul: The Journey to Damascus. But now he is playing Caiaphas’s father-in-law in Killing Jesus. How do the two roles compare?

“Annas is a supernumerary,” he replies. “The truth of the matter is, the real interesting part is Caiaphas, in this. Annas, in this version — in this rescension — is a really rather small part. The vanity of actors insists of course that it’s a very important part, but in truth, it’s a very small part. All the real fun exists for Caiaphas, lucky little bastard! My friend Rufus, of course.”

In addition to regaling us with various stories and opinions that have nothing to do with his current project — like how he refused to get a tattoo with the other members of the Fellowship of the Ring, and how the movie Braveheart “nearly wrecked the British nation” and was “an utterly false assemblage of history, by the way” — the Welsh-born Rhys-Davies says he has enjoyed working on Killing Jesus.

“The actors really do get on with each other, and they’re all very deferential to each other, which of course makes for a wonderful working atmosphere,” he says.

“The other thing is, I think there are more young actors and actresses in this show, as a group, who are going to have extraordinary careers, than I think any comparable production that I’ve been in for a long, long time. It’s just a very high density of real maturing talent that will go far.”

His parting words: “Take care, my boys and girls. Put verbs in my sentences.”