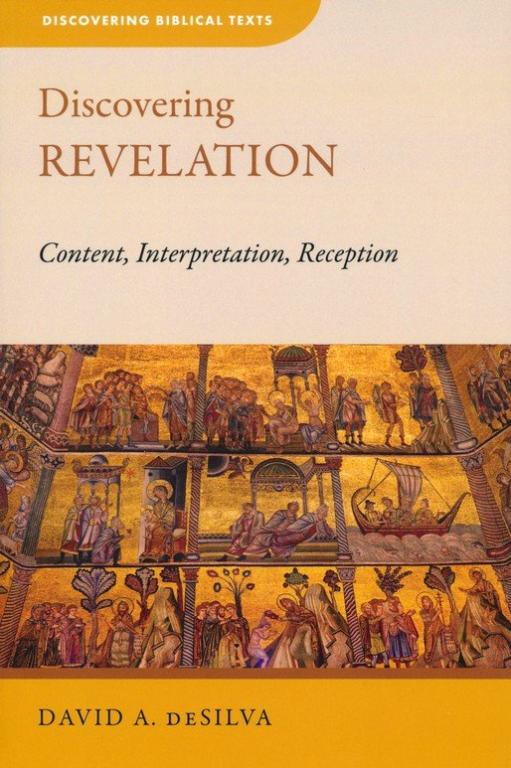

First-rate New Testament scholar David deSilva has written an intriguing book on Revelation entitled Discovering Revelation.

Recently, I caught up with David to discuss his book.

Enjoy!

There are countless books on the book of Revelation. Why did you write this one?

The short answer is that I was invited to do so by the publisher. The longer answer is that writing this book gave me the opportunity to explore the entire text of Revelation from start to finish (rather than focusing on particular passages or sections, as I had done in my earlier books on Revelation) and to do so not only from the perspective of the first-century audiences in Roman Asia but also to look at facets of the long history of Revelation’s interpretation in different sectors of the Church in different eras – what we call “reception history” or “history of interpretation.”

How is your book distinct from the other books on Revelation?

It is distinct from the many books on Revelation that treat the text like a blueprint for some alleged last seven years still in our future, that lead readers to think that the most important contribution Revelation has to make is information about a sequence of end-time events rather than a perspective on life in the here-and-now that facilitates faithful witness and steadfast obedience to God and his Christ. In this, however, my book has a lot in common with other thoughtful books written by scholars of Revelation for Christian audiences, such as Craig Koester’s Revelation and the End of All Things, J. Nelson Kraybill’s Apocalypse and Allegiance, or Michael Gorman’s Reading Revelation Responsibly.

My book might further distinguish itself from these, however, first in the attention I give to how Revelation has been interpreted in the Church in different periods and the insights or cautions we can derive from this history of interpretation; secondly in the attention I give to how Revelation sought to shape John’s own congregations’ interpretation of their local contexts and to incentivize their choosing a path of costly witness to, and distance from, the ills in the society around them.

I’m aware of the scholarship on this, but do you personally believe that John, the apostle and son of Zebedee, wrote Revelation? If so, why do you believe this? If not, who do you think wrote it?

There is a strong tradition for identifying the John who wrote Revelation with John the apostle, but I don’t lean on this tradition when interpreting Revelation.

First, John (Johanan) is one of the most common names in the Jewish subculture of the first century and the John who wrote Revelation gives no positive evidence of being John the apostle in particular. He makes no claim to apostolic authority or to personal acquaintance with Jesus during the latter’s earthly ministry. If anything, this John looks upon the circle of the twelve apostles from the outside (as in Rev 21:14) and presents himself, rather, as one of a circle of Christian prophets (Rev 22:6).

Second, the tradition that identifies this John as John the apostle arose in a context where the authority of a particular text would be affirmed by connecting it with an apostle or undermined by denying its connection with an apostle. It is difficult to discern whether genuine knowledge concerning authorship motivated the promotion of a particular book (e.g., Revelation), or whether the conviction that a particular book ought to be embraced as authoritative by the church universal led to claims concerning its apostolic origins.

So I read Revelation as a work by an otherwise unknown Christian prophet named John, and I try to read it on its own terms without looking to the very little we know of the apostle John as something that has any reliable explanatory power for what we encounter in Revelation.

Regarding the dating of Revelation, you favor a later date (A.D. 90s). Other scholars, however, argue for an earlier date (on or before A.D. 70). What do you believe are the weaknesses of the arguments put forth by John A.T. Robinson and more recently Jonathan Bernier that Revelation was written earlier?

It is admittedly unwise to be too dogmatic in terms of Revelation’s date and it’s a good thought experiment for all who hold to an early date to think about Revelation’s meaning and impact in the later first century and vice versa.

Robinson and Bernier both read Revelation 11:1-13 as a passage pertinent to the physical temple in Jerusalem and to the fate of that city, concluding therefore that a date before the ultimate and total destruction of Jerusalem makes the best sense of what we find there.

I am not persuaded that Rev 11:1-2 has anything to do with the physical temple in Jerusalem. This would be the only such reference in Revelation, which is otherwise wholly interested in the heavenly/cosmic temple, especially the holy places of God’s dwelling and the activity there (cf. 4:1-5:14; 6:9-11; 8:1-5; 11:19; 15:5-8).

Rather, I think John maintains a constant focus on the cosmic temple. The deceased (and perhaps especially martyred) saints occupy the places of protection in God’s presence beyond the material realm (cf. 6:9-11; 7:9-17; 14:13) while John’s audiences in the outer courts (the physical spaces of earth) continue to occupy the spaces vulnerable to attack by disobedient humanity. It is also not at all clear to me that John is thinking of Jerusalem at all in 11:1-13.

The only “great city” (11:7) in Revelation is “Babylon” (Rome) – and the much more cosmopolitan, diverse city of Rome is a much likelier place for “peoples and tribes and languages and nations” (11:8) to be gathered to view the dead witnesses than Jerusalem. A lot hinges on whether we understand this city to be symbolically characterized as “Sodom and Egypt” but geographically defined as “where also [the] Lord was crucified” (11:8), or whether it is symbolically all three.

Craig Koester explores a fascinating reading of Revelation whereby 11:3-13 and 17:1-18:24 depict alternate futures for one city – Rome – which faithful (if costly) Christian witness can affect if believers will take on the role of the witnesses. At any rate, a literalist reading of 11:1-2 and the last words of 11:8 seems a shaky foundation for a pre-70 reading.

The other pillar of this view is the “head count” of the beast in 17:9-11 and the suggestion that John is indicating an unbroken line of emperors starting with either Julius or Augustus Caesar, landing us on Nero or Galba (thus around 68-69 CE).

But the beast has seven heads because it is the amalgamation of the four beasts of Daniel, which collectively had seven heads and ten horns. It is convenient for John that this lines up with the seven hills for which Rome was famous in the early empire; it seems a stretch also to expect this to provide a comprehensive head count of all the emperors from the beginning to the time of writing.

The important thing for John and his readers is that they are living under the sixth in a series of eight – the end of the beast’s regime is thus truly at hand! Notice that, unlike the author of 4 Ezra, John never indicates that these heads are a complete set of rulers – a first, a second, and so forth – nor gives any clues by which any are to be identified except the obvious one: the sixth “is” the current ruler, whose identity John’s readers knew immediately but we will never know certainly.

But such weaknesses in the argument for an early date do not in themselves render the later date more certain. For this, I would point to (a) the thoughtful reflection upon Nero and the character of his rule as a revelation of “the beast’s” true colors (13:18); (b) the resonances with wider fears/expectations of a “returning Nero,” reflected in historical movements to place a “Nero” on the throne as late as 88 CE; (c) the reflection of the civil wars of 68-69 as a “mortal wound” that has already been healed (i.e., in the establishing of the Flavian dynasty – at the very least in Vespasian’s secure consolidation of his power) and the renewed enthusiasm for the worship of the emperors on this very basis; and (d) the central importance of worshiping or abstaining from worshiping the emperors, reflective perhaps of the increased fervor for imperial cult particularly in the cities of Roman Asia late in the first century.

Expound on the way Revelation was written. How does the book work exactly for the reader?

I think it essential that we stop thinking about Revelation as a book written in some mysterious code needing to be interpreted – and, moreover, needing to be interpreted in connection with features of our present or future landscape. It is a book that was written to interpret its first audiences’ landscape and the challenges they faced in their situations in light of God’s perspective on it all.

It is a piece of ideological warfare, a frontal assault on the majority’s perspective on Roman rule, the Roman economy, the emperors and the honors offered them, a re-evaluation of these features of the life of each of the seven cities in which John’s audiences live and move in light of the revelation of God’s character, righteous expectations, and interventions promised in the Jewish scriptures and the teachings of Jesus.

John’s audiences are reminded of what everything around them looks like from the perspective of God’s throne, what their neighbors worshiping their idols look like from the perspective of the hosts of heaven who know where the true center of power and honor resides, what the Roman economy looks like from the perspective of the prophetic critiques of earlier centers of empire like Tyre and Babylon (notice how much of Revelation is plucked out of the pages of Isaiah, Ezekiel, and Jeremiah!), and so forth.

And Revelation sets all of these insights – and, with them, John’s congregations – in the midst of a narrative in which God’s perspective is the one that ultimately matters, given God’s forthcoming interventions in the course of this world’s empires’ story.

Where do you stand on the millennium? E.g., post-millennial, pre-millennial, etc. and why?

I read the vision of the thousand-year of the saints in Rev 20:4-6 – specifically enjoyed by “those who had been beheaded on account of their witness to Jesus and on account of the word of God and whoever did not worship the beast or its image and did not receive the mark upon their forehead or upon their hand” (20:4) – as a promise specially made to the most marginalized of Christ-followers, or to those who might thereby be emboldened to embrace a costly course of witness and obedience, that any extraordinary degradation they might experience in the present era for God’s sake will be met with all the more extraordinary honors in the age to come.

Indeed, since the “first resurrection” leads to participation in this kingdom, and since experiencing the “first resurrection” means removal from the threat of the “second death,” those who face paying the ultimate cost for their faithfulness are all the more emboldened to accept that cost. But I find it difficult to remove the image of the millennial kingdom from its pastoral and rhetorical purpose, as if it is now some independent reality in an interim between the normal course of history and the eternity of God’s kingdom – one that I should imagine is promised you and me without our also facing those choices and consequences.

So I’m not pre-millennial, post-millennial, or a-millennial. I merely acknowledge the goodness of the God who assures his servants who have been specially marginalized that their honor will be specially vindicated.

If you can put it in a paragraph, what do you believe the main point of the book of Revelation to be?

God’s people have to keep testing the narratives that their society spins for them against the narrative of God’s creation of all things, redemption of all peoples in Christ, and inevitable reassertion of rule over all elements of his creation, with the result that we choose our actions and chart our courses in this life always in the way that is consonant with, and wise in light of, the second narrative.

In that way, we will always speak and live as witnesses to the ultimate truth of that narrative and, to the extent that we do this well and fully, give the people around us the opportunity also to break free of their captivity to the world, the flesh, and the devil as our witness opens them up to God’s possibilities for life now and life forever. More than anything, John wants Revelation to motivate faithful witness in the midst of the here and now to the unseen reality of God and his Christ and the ultimate advantageousness of “keeping the commandments of God and the testimony of Jesus” in every situation, no matter what the cost in the short-term.