Back in March, I was introduced to a new author who I had never heard before. Marc Schelske attended my SCRIBE 2017 mastermind event for authors in March.

It was at SCRIBE that I learned about Marc and his book. And that led to this interview.

I enjoyed Marc’s book and believe it’s a valuable resource. In the following interview, Marc tells you all about it.

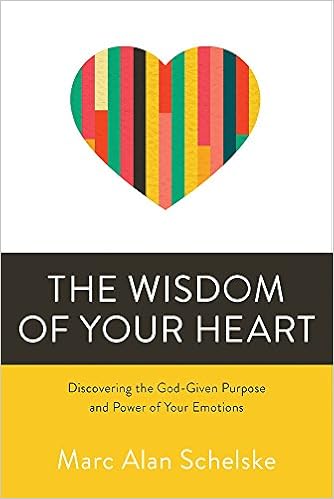

Marc’s book is called The Wisdom of the Heart: Discovering the God-Given Purpose and Power of Your Emotions.

Enjoy!

Instead of asking, “What is your book about,” I’m going to ask the question that’s behind that question. And that unspoken question is, “How are readers going to benefit from reading your book?”

Marc Schelske: They are going to grow up a bit. At least, that’s my hope.

We think of growing up as learning to tie our shoe laces, eventually getting a driver’s license and then a job. But the sad truth is that there are a lot of adults out there—and many of them in the church—who have adult obligations, responsibilities, and problems, and they are trying to tackle all of that with the emotional maturity of a child. Emotional maturity in our culture has meant learning to “just stuff it,” or finding a socially acceptable way to medicate our pain and uncertainty. Many of us have been taught that the more spiritual you become, the less emotional you’ll be. That’s all rubbish, and it lies at the heart of broken relationships, broken churches, and dry, joyless religion marked by obligation.

So, my intention and hope is that The Wisdom of Your Heart can help people see their emotions differently, and in doing so, help them discover a more mature way, and more spiritually impactful way, of listening to their emotions. After all, God gave us this incredible method of knowing and experiencing the world. We really need to learn to use it!

What motivated you to write this book?

Marc Schelske: I didn’t set out to write a book. I came to the end of my own rope. My own emotional immaturity and brokenness led to some very difficult and painful experiences. I was just not equipped to handle them. I was living 90 miles-an-hour, doing my best to be a “good pastor” in the active, young church I served. I was not taking care of myself. I had very few people who knew the reality of my inner life. I was disconnected emotionally with myself and the people around me, and had no idea of the damage I was doing to them. Everything important to me—my family, my marriage, my ministry—all of it was heading toward catastrophe.

A couple of close friends and mentors stepped in. I talk about them in the book. That led to me taking the terrifying step of attending a retreat about pastoral burnout. The things I learned there revealed truth about my heart that I had been blind to. I realized that I needed help. That led me to enter therapy with a very skilled, compassionate and wise therapist. She was also a Christian who had years of ministry leadership experience, and so she knew exactly where I was at.

As I progressed, I began sharing what I was learning with my church. I was no longer in a place where I could pretend to have it all together. My only credibility was in telling my story truthfully. For someone who had spent decades as a performer, doing everything possible to

please people, and to live up to some mythical standard of what a “good pastor” looked like, this was deeply frightening. But I was shocked. As I shared my story, and what I was learning, people were deeply supportive. They wanted to hear more. During a two year period, I presented two sermon series on emotions and emotional growth as a part of discipleship. In over twenty years of preaching, I’ve never had such a positive response from people. So, I began sharing more and more, and eventually that led to The Wisdom of Your Heart.

Tell us a bit about the experiences that shaped the insights in the book.

Marc Schelske: I sketched that out in the last question, but I’ll share two specific experiences that impacted me deeply.

The first was a train wreck that happened at my church. (I write about it here.) I was in a high intensity meeting about a controversial decision. Someone said something inflammatory. Someone else was hurt and they reacted. I stepped in to redirect and de-escalate the situation. I thought I was doing the right thing, and I thought I was doing it well. But what I did to intervene ended up hurting someone deeply. I was shocked at how deep their response was. I could not understand how the whole thing went so far sideways But, of course, being so disconnected from my own emotions, I was not able to key into the emotions of the people around me. I was just trying to relieve anxiety and fear, and instead caused a lot of damage. I went over and over this situation in my mind for months, and finally realized I was part of the problem.

Another significant experience was the retreat for pastoral burnout that I mentioned. I talk about this in detail in the book. At one point on this retreat the facilitator handed out a little chart listing emotions and their meanings. Then he began walking us through it. “This is anger,” he said. “Anger is the emotion you feel when you, in your own private logic, experience being violated.” He went like that through the whole list.

At first, I was pretty offended. I mean, I’m an adult. Don’t talk down to me. You don’t need to tell me what anger and sadness and fear and joy are. I’m not an imbecile! But later that weekend, when I was journaling about this, I realized that not once in my life had anyone ever explained the meaning of emotions to me. Not my parents, not my teachers, not my pastors and youth pastors. Not my professors, when I was preparing for ministry. No one—ever. And I wondered how my life might have been different if that had happened.

My dad died unexpectedly when I was eleven. How might the course of my development have changed if someone could have sat with me when I was grieving, and told me, “This thing you’re feeling, it’s OK. It’s right and normal. That terrible ache in your gut that feels like a never-ending pit, that’s grief. You’re going to feel it for a while, but nothing is wrong with you. You don’t need to hide it. You don’t need to cover it up. You’ll be OK, but for right now this is your brain and body’s way of letting you know how big your love for your dad is, and how much you miss him.”

No one in my life was equipped to say something like that. My church didn’t have any tools to help me understand and process it. The people around me were mostly uncomfortable with my grief, and so they ignored, or disappeared, or offered an endless stream of useless platitudes.

That’s just one life experience, and I know everyone has something similar in their story. So, it’s my hope that perhaps I can help change the conversation in the church, so that we become more equipped to help each other through these moments.

Early in the book, you lay out 4 myths about emotions that you picked up in church. Which of those do you think is the most destructive and why?

Marc: The first three myths all build on each other and lead to the final one, which is the most destructive of all.

Many of us were taught that emotions always lie. If we believe this, we will try to ignore our emotions and we will miss any helpful truth they carry. Then we justify ignoring emotions by saying that emotions are always shallow and transitory. With this myth, we demean our God-given emotions, and elevate a life of duty and obligation as the highest Christian good. That makes sense to us because we’ve been taught that God isn’t emotional. Taken together, these three false stories about emotion lead us right down the path to the worst myth of all: The more like God we become, the less emotional we will be.

If we were raised in the church, we were raised with the desire to be like Jesus. Ephesians 4 tells us that God’s project in our lives is to mature us after the image of Christ. We’re told to be Godly—which means becoming more like God. Well, if we believe that God isn’t emotional, then naturally, we will think that the more like God we become, the less emotions will feature in our lives. So we picture stoic saints as the pinnacle of Christian maturity, and when we ourselves feel a wave of fear or anger or sadness, we wonder if we’re being bad Christians by feeling these things.

I grew up in a fairly conservative Christian community, and it was not infrequent that we were taught about the Christian martyrs. I can recall the vivid memory of being taught about those faithful Christians who went to the stake or the lions, and when death was upon them, instead of crying out in fear—like any normal person would—they sang hymns and evangelized the people watching them. Now, I don’t mean to belittle the grace God might give someone in the moment of martyrdom. I believe that can happen. But I know that as a child, these stories painted a picture of Christian discipleship that included little room for real feelings. If these heroes could face the flames without crying, I certainly could be a “big boy” and keep my tears to myself.

The result of thinking like this is generations of Christians who are disconnected from their own emotions, and as a result, unable to experience intimacy with others, even with God. It’s led to churches splitting because they didn’t have the tools to process the powerful emotions that emerge around disagreement. It’s led well-meaning preachers to tell abused wives to just pray

harder for their husbands, and to tell the abusing husbands to just read their Bibles more, so they can love their wives like Christ loves the church. All because we have been trained to disregard our emotions as false, shallow, and ungodly.

In the book, you make a pretty startling claim. You say that emotions always tell us the truth. How can that be? Aren’t emotions subjective?

Marc Schelske: It is a pretty outlandish claim, considering what most of us were taught about emotions, growing up. But it’s true. Our emotions are always telling us truth; just not always the truth we expect. To explain I need to give a little background. When we have a feeling, our emotional response system is feeding us data. It’s information about our inner world and outer circumstances. That information isn’t moral or amoral, it’s not righteous or sinful. It’s just information.

So, when you feel the rush of anger, for example, your emotional response system is giving you information. Now, as best we understand the mechanisms of emotion in the body and the brain, what we think of as emotion is a composite experience. There are four parts and they happen in a sequence, although the sequence happens so quickly it feels nearly instantaneous to us.

First, there’s a reaction in our body. Our face flushes, our heart beats faster, etc. We used to believe these changes happened as a result of feeling an emotion. But current brain studies have shown that in nearly every case, this bodily response happens before our conscious brain is even aware that we are having an emotion. It’s crazy, but it’s true. I go into this more deeply in the book.

Second, our conscious mind becomes focused around an automatic pattern of thoughts. Angry, defensive thoughts, for example, or whatever is congruent with the reaction we’re having. This is when we begin to be conscious that we’re feeling an emotion.

Next, our thinking homes in on an object we believe elicited this reaction in us. So, we tunnel vision in on the driver who cut us off. We may not be right about what caused the reaction—in many cases we’re not. Finally, all of this comes together in a story we generate in our mind. “That guy is a dangerous, selfish, idiot!” This mental story is what drives our reaction.

Subjectivity enters into the equation in our interpretation. Our interpretation is infallible. Often our interpretation is just us leaping to a conclusion. If we’re emotionally immature, our interpretation is almost always selfish. If we are under severe stress, have deep brokenness, or mental illness, or if we’re using substances, our interpretation can be further twisted.

But at the heart of the system is useful data. When that driver cuts me off in traffic and anger bursts in on me, that anger is telling me something true about my inner world and outer circumstances. The driver did indeed do something threatening. If he cut me off too closely,

and I wasn’t watching, we could have both been injured. That’s a real threat that I needed to act on. And I needed to act on it more quickly than my reflective thinking mind would allow.

But let’s go deeper. If my anger remains, and I keep ruminating about that guy and how he cut me off, now I’m no longer reacting to the moment. Something else is surfacing. Anger is the emotion you feel when, in your own private logic, you (or someone you love) is violated. So who or what was violated? The guy is long gone. I didn’t get in an accident. No one was injured. What was violated? Well, one painful answer may be that my pride was violated. How dare that guy cut me off? I’m not here for people to bully. Someone needs to teach that guy a lesson! Now, if I’m willing to listen, my anger is carrying a deeper truth. I don’t like being disrespected. It’s so important to me that if someone treats me with disrespect, my heart will rise up in indignation against them. I may even retaliate. My emotion of anger is pointing a finger at my own heart, revealing a truth that perhaps God wants me to confront and deal with.

Learning how to see the truth in our emotions is the task of emotional maturity. It’s not easy, because we like to feel justified, but if we’re willing to humbly listen and look within, there’s a lot for us to learn. Not only that, I think learning these lessons is one of the ways we grow in the image of Christ.

What would you say to those who would view you as some sort of an emotional master? When something happens like this—say your example of a person cutting you off—do you just shake it off and not feel those feelings?

Marc Schelske: Not at all. In fact, that’s just the point. We will never stop feeling emotions. Emotions happen to us. The initial emotional response system is nearly autonomous. So, I still get angry when I’m cut off, or frustrated when my kids don’t obey. I still over-react when my wife says something that is vaguely critical. All that still happens—although my reactions have tempered, and there are more and more times when I can see what’s happening and make a shift in my thinking and feeling.

What’s different for me now, after learning all of this, and spending hours and hours journaling through my feelings before God, is that now I am not a slave to my emotions. I am much more quick to understand what’s happening in me and why. “Much more quick” may still mean it takes me days and days to sort through a really confusing or painful interaction. But now I’m not living under the added stress and anxiety that comes from worrying about why I’m having these emotions, or worrying about whether I’m a good Christian for feeling this way.

These days, my emotional life is a central part of my relationship with God. I talk with God about what I’m feeling. I ask for discernment to untangle the threads. I argue with God when it turns out the problem is me. But all of that means that my relationship with God is more truthful than it’s ever been, and that means intimacy is possible or me in a way it never was before.

Learning how to do this is hard—at least it was for me, and I suspect it will be for people who, like me, are living disconnected from their emotions. The first time I tried journaling through an emotionally painful interaction, it took me hours. But this is a developmental skill. It’s something we can learn, and get better at. With practice, we begin to notice habits and patterns in our own lives. This is one of the places that I think God has helped me grow the most. Processing this stuff before God has revealed deep veins of pain and anger in my life. It’s helped me see how I self-justify in relationships, and why sometimes I will lie to avoid pain. These are matters of deep character growth, and they just weren’t coming up through the traditional kinds of prayer and Bible study and discipleship that I’d been practicing for decades.

You’ve mentioned journaling through your emotions before God? What does that look like for you?

Marc Schelske: Processing emotions is hard because they happen inside us. When they are really powerful, they can feel like they ARE us, like our whole world is that particular feeling. So, while it’s possible to process emotions mentally, it’s a really advanced skill. So, I recommend people who want to bring their emotional life out into the open do it in a journal.

The act of writing these things down helps to make them tangible. Seeing the words on the page allows you to re-calibrate and refine the truth of what you’re saying. “I’m upset,” is almost a useless phrase. What does it mean? Are you angry (feeling violated), sad (feeling loss), fearful (feeling in danger), jealous (feeling a relationship is threatened)? Landing on anger isn’t enough. If anger is the emotion of feeling violated, is that true? Were you violated? If so, in what way? Was it a violation of your expectations? Or of your hopes? Or of your will? Or of your pride? Did the person who violated you mean to? Was it an accident? Do they understand that they hurt you? All of this is complicated stuff—made more complicated by our heart’s constant desire to self-justify. So, getting it out of your mind and onto paper helps to untangle the threads.

There are many ways to do this, but in The Wisdom of Your Heart, I walk the reader through a process that mirrors the natural sequence of our emotional response system. It’s a process that can be done fairly quickly, and mentally when needed. And it can also be done at great length and depth, where you really dig down into what is happening in your heart and why.

I call it the Five A’s, since it’s defined by five words that start with A. Attend, Articulate, Ask, Assay and Apply. In the book, I show how to use this tool, but I’ll give you a quick sketch here.

Attending is about noticing what is happening in your body and mind. This in itself is a skill. In our busy, fragmented world, many of us are quite bad at being present. We’re not really present to the people we’re with. We’re not present to the circumstances we’re in. We’re distracted by our phones and our attempts to avoid discomfort (which is one of the reasons our faces are in our phones so much.) So, we start by Attending to what is happening in our body and thoughts, just noticing the changes happening.

Articulating is about naming the experience we’re having. Saying that we’re “upset” or “frustrated” isn’t enough. This is about noticing what is happening in our body and mind, and being very truthful and clear about what’s happening.

Then we Ask. This is where we consider the possible meanings of the emotions we’re feeling. Why has this feeling come over us? What do think has caused it? Are our assumptions reasonable? Do we need to gather more information, to keep from jumping to conclusions? Do we need to ask God for discernment to see what’s happening?

Once we’ve gathered all the information, we Assay it. During the Gold Rush, the town Assayer was the man who would weigh and measure the gold the prospectors brought in. He’d sort the fools gold and other worthless junk from the real gold, and tell the prospectors what the real gold was worth. This is what we do now. Looking at what we’ve learned, we decide what is worthwhile and what is not worthwhile.

Finally we Apply. This is where we allow the emotional energy that’s build up in us to manifest itself in some action. But the process of spiritual and emotional growth means we are going to be less and less reactive, and more able to choose an action that is loving.

With practice, this process becomes just a natural part of thinking about and praying through the emotional experiences we’re having in life. I still journal nearly every day, and nearly every day some part of my journaling has to do with my emotional life. This is a form of prayer for me. The Psalmist, in Psalm 139, wrote, “Search me, God, and know my heart; test me and know my concerns. See if there is any offensive way in me, and lead me in the everlasting way.” Journaling through my emotions in this way is how I experience that kind of interaction with God, and it has deeply changed me.

So your book comes out September 1st. Is there anything else we should know about that?

Marc Schelske: Well, September 1st is when the book will be available online and in bookstores, but you can order it now. In fact, if you pre-order there are some helpful things you can get that will expand the impact of the book.

There’s a full-color quick-reference bookmark that can keep the basics of the emotional response system and the 5 As in front of you. There’s also a full-color two-sided info-graphic that includes a basic emotions chart (like the one that retreat facilitator walked me through), and a detailed walk-through of the 5 A’s with prompter questions. This would be great to keep in your journal. I also created a 30-page small group facilitator guide that you can use to take a church group, book group, or group of friends through the material in the book. In addition to this, on my website in the next month, there will be 4 online video courses that will go along with the book, to help deepen the learning and life change that someone has as they go through the book. You can pre-order the book and get the bonuses at www.TheWisdomOfYourHeart.com.

Any final words?

Marc Schelske: Most of all, I’m hopeful that this book can be a resource for the church. We need to get better at this stuff. Better and more comfortable talking about emotions. More capable of compassionately sitting with people in great grief. Better at teaching our kids what emotions mean, and how to understand them. Better at theological conversations that touch on emotional experiences.

The place I found myself in, now eight years ago, was brutally painful. And the consequences for me, and for the people I love, were terrible. I hope that in some way, through this book, I can come alongside other people in similar places. I hope that this book can offer them hope that change can really happen, and guide them on a path forward in understanding God, themselves, and their emotions in a better, healthier, more life-giving way.