I just finished a lovely week with my brother Vaughn and sister-in-law LaVona in Santa Fe, a trip I’m sure that will be showing up in posts and pictures here for the rest of the summer and beyond. Santa Fe has a special place in both Jeanne’s and my history. I spent four years in the seventies earning my Bachelor’s degree at St. John’s College in the foothills of the Sangre de Cristo mountains; Jeanne and I spent the first five months of our lives together there in 1988 as she finished earning her Master’s degree at St. John’s.

My brother’s and sister-in-law’s apartment is only a mile or so from Jackalope Pottery, a Santa Fe institution that has to be experienced rather than described. Upon hearing that Vaughn and LaVona had yet to visit Jackalope Pottery, Jeanne accused them of sacrilege and made me promise that I would get them there. I did, returning home with a wind chime made at Prairie Dog Glass that is on the premises. The visit took me back not only to memories of previous years in Santa Fe, but also to other places where I have encountered jackalopes (and other important creatures) over the years.

My brother’s and sister-in-law’s apartment is only a mile or so from Jackalope Pottery, a Santa Fe institution that has to be experienced rather than described. Upon hearing that Vaughn and LaVona had yet to visit Jackalope Pottery, Jeanne accused them of sacrilege and made me promise that I would get them there. I did, returning home with a wind chime made at Prairie Dog Glass that is on the premises. The visit took me back not only to memories of previous years in Santa Fe, but also to other places where I have encountered jackalopes (and other important creatures) over the years.

During my sabbatical at an ecumenical institute in Minnesota almost fifteen years ago that began in the middle of January, native Minnesotans kept promising that the ice would eventually leave Stumpf Lake behind my little apartment and winter would give way to spring. They didn’t add that when May began most of the tree buds still would be buds. One native added that I would know when it would not snow again when the loons returned to the lake, because the loons never show up until winter is over.

Having no experience with loons, I had no idea whether this is a provable fact or yet another of the many tall tales I suspected the natives enjoy telling each new batch of outliers who live with them from semester to semester. And it isn’t just Minnesotans who enjoy doing this. In the little Wyoming town in which I lived for a short while four decades ago, there was a local watering hole called the “Jackalope Café.” The inside of the bar was a taxidermist’s heaven, with mounted heads of buffalo, moose, bear, elk, deer, some sort of wild cat, and bighorn sheep crowding for space.

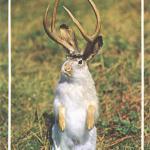

Always seated at the bar was a collection of interesting human specimens, cowboys and ranchers who all were missing at least one body part—an eye, a finger, several teeth, something. Over the bar were other unusual specimens, the heads of what looked for all the world like large jackrabbits, but sporting horns. And not just any horns—they look just like the racks of pronghorn antelope.

These heads were from specimens of the West’s most mysterious and mythical animal, the jackalope. A traveler can find evidence of the jackalope throughout the West, from the café in Afton, WY to Jackalope Pottery in Santa Fe. In addition to the ubiquitous mounted jackalope heads, there are jackalope books, jackalope post cards, jackalope key rings, jackalope magnets, jackalope shot glasses, jackalope t-shirts—you get the idea. The regulars in the Jackalope Cafe had an endless supply of jackalope stories–how hard it is to find one, how elusive they are, their natural viciousness when cornered—stories that ratcheted up in complexity and detail when someone obviously from out of town walked through the door.

There’s nothing a rural Westerner enjoys more than astounding an Eastern city person with jackalope tales. Because as wonderful as the stories are, jackalopes don’t exist. The heads on the wall really are jackrabbit heads with antelope horns stuck on top of them. They are the source of many laughs when yet another gullible rube from the East has been duped. But don’t be too hard on the rubes—people in England thought that the preserved bodies of platypuses brought back from Australia were beavers or muskrats with duck bills sewn on them until they saw a live one. And anything that’s as lucrative and entertaining as the jackalope must have some truth to it. As one of my colleagues once said after the veracity of one of his tall tales was challenged, “Well if it isn’t true, it ought to be true.”

There’s nothing a rural Westerner enjoys more than astounding an Eastern city person with jackalope tales. Because as wonderful as the stories are, jackalopes don’t exist. The heads on the wall really are jackrabbit heads with antelope horns stuck on top of them. They are the source of many laughs when yet another gullible rube from the East has been duped. But don’t be too hard on the rubes—people in England thought that the preserved bodies of platypuses brought back from Australia were beavers or muskrats with duck bills sewn on them until they saw a live one. And anything that’s as lucrative and entertaining as the jackalope must have some truth to it. As one of my colleagues once said after the veracity of one of his tall tales was challenged, “Well if it isn’t true, it ought to be true.”

At least loons are real. I know they are, because they eventually returned to Stumpf Lake (and it didn’t snow after that, either). They showed up on a misty April morning, the morning after Jeanne’s week-long Easter visit from Rhode Island ended, a week during which she saw lots of little birds, a million squirrels, one eagle off in the distance, and no loons (or deer, fifteen of whom had an early morning breakfast picnic on the lawn in front of my apartment just before Jeanne came to visit).

The morning the loon pair arrived I heard their famous call. Later that day, upon hearing that I had seen and heard loons, one of my friends from Washington D.C. said “I’ve never heard or seen a loon. What do they sound like?” To which I replied, “There’s a reason for the saying ‘crazy as a loon.’ They sound like an insane woman’s laugh.” To which another friend, who is a bit of a know-it-all, replied “I’ve heard loons lots of times, and I don’t think they sound like that at all.” Oh well.

Jackalopes and loons. Although there’s a significant ontological difference between them, it’s probably just a quirk of natural selection that there are no horned bunnies. Maybe there were giant prehistoric carnivorous jackalopes who were the bane of the earth, who became extinct along with the dinosaurs for still unknown reasons. Why not? Horned rabbits don’t strike me as any less possible than water birds with long necks who sound like the Wicked Witch of the West. Annie Dillard, one of her generation’s most astute observers of the natural world, puts it this way:  “Look, in short, at practically anything—the coot’s feet, the mantis’s face, a banana, the human ear—and see that not only did the creator create everything, but he is apt to create anything. He’ll stop at nothing.” The natural world looks less like intelligent design and more like an explosion of exuberance.

“Look, in short, at practically anything—the coot’s feet, the mantis’s face, a banana, the human ear—and see that not only did the creator create everything, but he is apt to create anything. He’ll stop at nothing.” The natural world looks less like intelligent design and more like an explosion of exuberance.

“He’ll stop at nothing”—that’s a pretty good summary of God’s dealings with us. Poet and Benedictine monk Kilian MacDonnell writes of “Our preposterous God with a preposterous love,” and that’s just the right word for it. In the Old Testament stories, time after time I can hear God sighing, “Okay, people, let’s try this again. Just do this handful of things, and everything will be fine.” Then, of course, it gets messed up, God tries again, gets pissed off but doesn’t give up, and so on. Then God has an idea so out of the box, so off the radar, that it’s ludicrous in its originality. “I’ll become human.”

In a novel I finished recently, a character was explaining her decision not to convert from Christianity to Judaism when she married.

The great appeal of Jesus is the willingness of God to walk among the benighted creatures He just can’t seem to give up on. There is a glorious looniness to it—the magnificent eternal gesture of salvation, in the face of perennial, thick-headed human inanity! I like that in a deity.

So do I. This is one of those stories that not only should be true, it is true.