It is past time to admit a very hard truth: America’s poverty problem is also a depravity problem.

It is past time to admit a very hard truth: America’s poverty problem is also a depravity problem.

It is simply a fact that people who work hard, finish their education, get married, and stay married are rarely — very rarely — poor. There is no other proven formula for lifting Americans out of poverty. None. Food stamps don’t do it. Medicaid doesn’t do it. Soup kitchens don’t do it. Good intentions don’t do it. Hundreds of billions of dollars of transfer payments have not budged the poverty rate.

Simply put, any anti-poverty efforts not aimed at getting kids to complete an education, get married, and stay married are a waste of time. They may ameliorate immediate physical needs, but the very act of ameliorating those needs renders a destructive lifestyle sustainable and viable.

Walter Russell Mead reminded me of this reality in a must-read post discussing some rather sobering sociological findings. It turns out that poor, less-educated Americans are turning their backs on religion at a far greater rate than more-educated Americans. Here are the key findings:

The study also shows that Americans with higher incomes attend religious services more often, and those who have experienced unemployment at some point over the past 10 years attend less often. In addition, the study finds that those who are married (especially if they have children), those who hold more conservative views toward premarital sex, and those who lost their virginity later than their peers, attend religious services more frequently.

Indeed, the study points out that modern religious institutions tend to promote a family-centered morality that valorizes marriage and parenthood, and they embrace traditional middle-class virtues such as self-control, delayed gratification, and a focus on education.

Over the past 40 years, however, the moderately educated have become less likely to hold familistic beliefs and less likely to get and stay married, compared to college-educated adults.

In other words, vicious and virtuous cycles exist simultaneously. For the least-educated, the less they attend church the less they’re exposed to “middle-class values,” which causes them to engage in behaviors that further alienate them from church. For the educated, the cycle is the reverse. The church reinforces the values that permit them to maintain middle-class standing, which keeps them within the “familistic” culture — and in church.

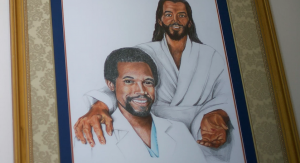

The result is a set of competing cultures, with social mobility defined primarily by the adoption of the behavioral practices of the opposing cultures. Illegitimacy and divorce are engines of downward mobility just as marriage and education are engines of upward mobility. Providing material support without contributing to cultural change is an exercise in futility and is often harmful. And the key to culture is Christ.

In short, the poor need Jesus but have never been culturally more distant from Him.

Mead says this distance is largely the fault of the church:

It is the most scorching indictment of America’s religious communities I can think of that more has not been done to reach out to those most in need of both the spiritual and the social benefits of faith. Every member of a religious congregation in this country should be asking how he or she could be doing more.

I agree in part. Yes, we should be asking how we can do more, but in doing “more” we should realize that our anti-poverty efforts largely address symptoms and not causes.

For many, many years I spent time “in the trenches” reaching out to at-risk youth. At first I was the stereotypical naive idealist. “All they need is love and a chance,” I thought. Working in mentoring programs, I spent untold hours playing catch, going to little league games, going to parks, and just hanging out with at-risk kids as part of a variety of programs. Seeing ragged clothes, I’d buy new clothes. Hearing that a mother couldn’t pay the light bill, I’d kick in and help. I spent night after night sleeping in homeless shelters, cooking dinners in the evening, pancake breakfasts in the morning, and fixing snack lunches for hard days on the streets.

I can’t remember when I first realized that I was accomplishing nothing of substance. A few car break-ins taught me that some guys saw me as an easy mark. A few pot purchases with the “gas bill money” taught me that others saw me as an ATM. Admonitions to “stay in school” had little appeal compared to drug-fueled orgies for kids as young as fifteen years old. I tried. God knows I tried. But it was all for naught.

Only one thing really worked. The Cross. There are kids today that Nancy and I worked with who are doing well, who are happily married, and who are pillars of their community. What made the difference for them? The Cross. It wasn’t about my words. It wasn’t about my effort. (After all, I tried just as hard or harder with other kids — who are now in prison or “baby-daddies” or both.) The kids who made it heard the Gospel, repented of sin, and were transformed through the renewing work of the Holy Spirit.

It’s trendy now for churches to put less emphasis on the Gospel and more emphasis on service. I’ve even heard Christians almost brag that their outreach efforts don’t include any proselytizing at all. This is tragic. Billions of dollars of “service” won’t change hearts and lives. We know that now. In fact, those very billions may very well numb the human heart to the gravity of its sin.

So, yes, let’s do “more,” but let’s make sure that “more” is aimed at the real source of American poverty — our depravity.

UPDATE: This post — along with a much shorter post on NRO — have triggered quite an interesting discussion. I unpack some of the theological issues surrounding “depravity” (including the obvious point that we’re all sinful and depraved) here.

In this post, I collect a variety of relevant federal statistics on poverty showing the impact of education and marital status on unemployment and poverty.

Finally, in this post (formerly the most-read post in French Revolution history), I address the question: What can I do to fight poverty?

This is an immense topic, and this post is just one part of a much longer discussion that I hope you’ll join. I’ll be posting quite a bit more in the next few weeks and months.