By Reed Metcalf

If you’ve been following the Fuller Blog the last few weeks, you may have seen our series of blogs working through the writings of Walter Brueggemann. My hope was to give folks an inside look into how our study in seminary affects our reading, writing, and preaching on Scripture. Today was supposed to cover the last section of Brueggemann’s Theology of the Old Testament, but something happened in my noggin that drove home the point of this entire series.

I was sitting in our mid-week chapel service at Fuller Seminary when things started to hit home. President Mark Labberton was preaching the passage where James and John want to sit at Jesus’ right and left in the kingdom (Matthew 20:20-28). He was driving home the point of James and John not understanding either Jesus’ kingship or the Kingdom of Heaven, and thus not understanding their request. Jesus’ kingship is based on humility, service, and self-sacrifice to bring healing and restoration to all the world; James and John seem to think this is about power and authority and might. They, like so many others in the Gospels, miss the point.

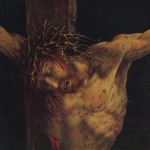

As I was sitting there listening, my synapses started firing (it happens occasionally). Jesus, we Christians believe, “was God” (in the words of John 1), is the Second Person of the Trinity, is a part of the mysterious and completely transcendent God called Yahweh in the Old Testament. Here in chapel I was contemplating Jesus willingly emptying himself of his God-ness to go to the cross (following Philippians 2), choosing a cup no one expected the Holy One of Israel to drink: to be part of a rebellious species called humanity, to preach repentance and good news, to serve and sacrifice, to die on an imperial cross in an act of ultimate love. It is a story Christians know well, perhaps so well that we forget the larger story it—and we—are a part of.

And this is where Brueggemann comes in.

Brueggemann talks about the Old Testament witness having a tension; God is so big, so complex that we cannot fully comprehend him. We instead see the witness of Israel pull in separate directions, most notably between tendencies of Yahweh assert his holiness (or sovereignty) and his love (or solidarity). God is concerned for both his people Israel and his own godliness. When Israel is in trouble, he is quick to rescue; when Israel gets too chummy, God is quick to remind that this is not a relationship between equals. A great deal of trouble befalls Israel when they take God and his holiness lightly in the Old Testament. Yahweh’s devotion to Israel elicits a specific response, a response of being a holy people, a light to the nations. Their failure—or, rather, their lack of willingness to accept that identity—leads to exile. The holiness of God wins this specific tug-o-war against the solidarity of God, and Israel finds itself rejected by the God it rejected.

But not for long.

God chases Israel down again and leads them out of exile. Again and again, the Holy God shows mercy and solidarity, love and forgiveness to triumph time and again. And we are surprised, says Brueggemann, to see God do this for Egypt and Assyria and Persia and Babylon as well.

The God whose holiness demanded so much set aside that holiness for the sake of solidarity.

Yahweh gave up a crucial part of himself to be with us.

Jesus emptied himself of his God-ness to love us.

If holiness is about cleanness and purity, a setting aside for a special purpose, the cross is the exact opposite. It is dirty and crude and shaming and horrible.

When we think of the God who said “no one can see me and live” not only becoming visible to us but vulnerable to us, it drives home the amazingness of grace. Yahweh left behind holiness for love. He became dirty and cruelly treated and shamed so that we may never again be shamed or guilty or left for dead. The Holy One became unholy for us. This is the true scandal of the cross.

And for clarity’s sake, this is not something we need to beat ourselves about. Instead, we receive the free grace and love of a God who would do anything and go anywhere to bring us back.

My time in chapel was overwhelming. The cross and all it symbolized was amplified and newly illuminated because of my study. It was like seeing a new facet on a diamond. The diamond was always beautiful, but I can appreciate and understand that beauty just a bit more.

This is why we study. We do not expect to exhaust the Gospel, but we do hope to see yet another facet, to know how to explain its beauty to those who have not yet seen or believed it, to more fully articulate the vast love of an endless God.

Thanks for the help, Dr. Brueggemann.

We’ll continue our working through Brueggemann’s books next week. Register for his lectures at Fuller Seminary here.

Reed Metcalf works as a Media Relations and Communications Specialist at Fuller Theological Seminary. He writes for and curates the Fuller Blog and contributes regularly to FULLER magazine. He graduated with his MDiv from Fuller in 2014 and co-founded the Fuller Faith and Science student group. Reed and his wife Monica live in Pasadena, CA, where he is an ordination candidate in the Free Methodist church. Follow him on Twitter at @reedmetcalf.

Follow Fuller Seminary on Twitter at @fullerseminary.