Celebrity business titans! Immigration controversy! Booming cities and dying rural areas! Yellow journalism! Political chaos! Scandals! Populist demagogues!

That describes the “Gilded Age” of the late 19th century, with its “robber barons” like Carnegie, Vanderbilt, and Rockefeller. And it describes the economic, political, and social scene of today, with our high-tech barons like Elon Musk, Jeff Bezos, and Mark Zuckerberg.

A big difference is that while both climates inspired a populist backlash, William Jennings Bryan kept being defeated. But Donald Trump got elected.

So observes Matthew Continetti, drawing on American historians who are also noting the parallels:

[Historian] Niall Ferguson mentioned a lecture he first delivered in 2016 on the five ingredients of a populist backlash. Recalling the Gilded Age of robber barons, bimetallism, the Panic of 1873, and Yellow Journalism, Ferguson pointed to income inequality, immigration, elite corruption, financial crisis, and demagogues as commonalities between that distant era and our own.

In an excellent 2017 presentation, D.C. consultant Bruce Mehlman noted further parallels. Both epochs had massive changes in employment. During the Gilded Age, agricultural jobs disappeared as workers poured into manufacturing. Today, manufacturing jobs go missing as workers enter the service sector. Disruptive technologies and the men who amass fortunes from innovation also define both periods. Then it was Carnegie and steel, Rockefeller and oil, Vanderbilt and railroads. Now it is Sergey Brin, Larry Page, and web search, Jeff Bezos and e-commerce, Mark Zuckerberg and the social network.

Like today, the America of the late 19th century was divided between the party of the economically ascendant cities and the party of declining and forgotten rural areas. Only then it was the Republicans who were city-dwellers and the Democrats who were Southerners and Midwestern farmers. Like today, the outsider party was taken over by a charismatic populist. Yet William Jennings Bryan lost all three of his campaigns for president. Trump won on his first attempt.

[Keep reading. . .]

Continetti’s political analysis, which takes into account both the scary similarities and some wild-card differences, is well-worth reading.

For example, in the Gilded Age, the Republicans ruled from the economically booming cities, while Democrats simmered in resentment on the farms and small-towns, creating a populist reaction.

Today, the Democrats dominate the cities and have most of the new robber barons and their wildly successful industries on their side. Republicans are the ones simmering in the countryside and turning to populism.

Both periods, though, featured unstable political majorities–including presidents elected with less than a majority vote–so that the governments were able to get little done. The Gilded Age is called “the Era of No Decision.” The problem then for political parties is the same as the problem now:

To win a majority, a party must appeal to the large number of voters who do not identify as either a Republican or a Democrat. Yet, once in office, the ideological nature of our parties moves them to enact policies anathema to the very people who brought them to power. “In short,” Fiorina concludes, “the interaction between the close party divide and today’s well-sorted parties leads to ‘overreach,’ with predictable electoral repercussions. The center does hold, frustrating the governing attempts of both parties.”

Also, consider the meaning of the metaphor: “Gilded” means covered with a very thin layer of gold. The object appears to be gold, but it really isn’t. It’s made out of wood, plaster, or some other cheap substance. The gold, while genuine–just as the wealth of the 19th century and today is real–but it remains a superficial cover-up of a reality far less opulent and substantial.

How do you think that metaphor works with today?

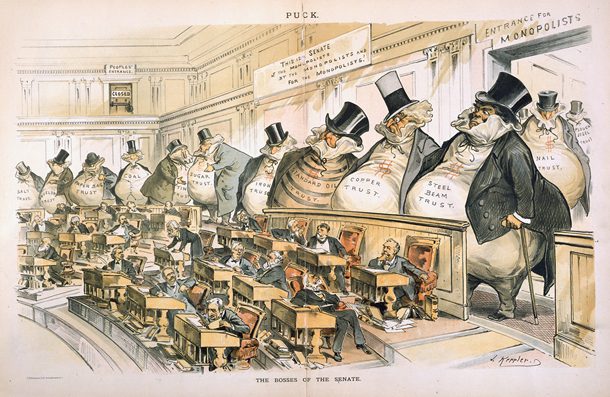

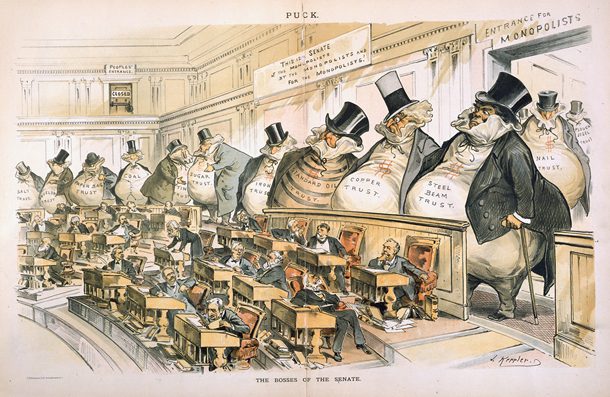

Illustration: “The Bosses of the Senate” by Joseph Ferdinand Keppler (1889) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons