Dean Acheson, who orchestrated the Marshall Plan and helped create the North Atlantic Treaty Organizaation, had no use for moralizing in foreign policy. He once said that listening to pious Canadians discuss foreign affairs was like listening to the “stern daughter of the voice of God.”

His point was that there’s a big difference between being moral and moralizing. Being moral is about changing the way you act and actually helping others. It requires humility and tolerance because it arises from an awareness of one’s own moral failings.

Moralizing, by contrast, is about changing the way other people act—by force if necessary. Moralizing breeds intolerance and even tyranny because it springs from a belief that, like the pious Canadians, not only do you know the truth but you also have a solemn duty to impose it on others.

In America today, being moral is out and moralizing is in. Just witness the nonstop spectacle of moralizing everywhere you turn—from The New Yorker’s panicked denunciation of Chick-fil-A’s “infiltration” of New York, to gun control activist David Hogg’s boycotts, to the protestor with a megaphone shouting in a Starbucks clerk’s face.

[Keep reading. . .]

The article goes on to discuss the various indignations expressed in the name of political-correctness. These, says Mr. Davidson, are examples of “moralizing,” rather than actual “morality.”

First of all, for the record, Dean Acheson was alluding to the first line of William Wordsworth’s great poem Ode to Duty.

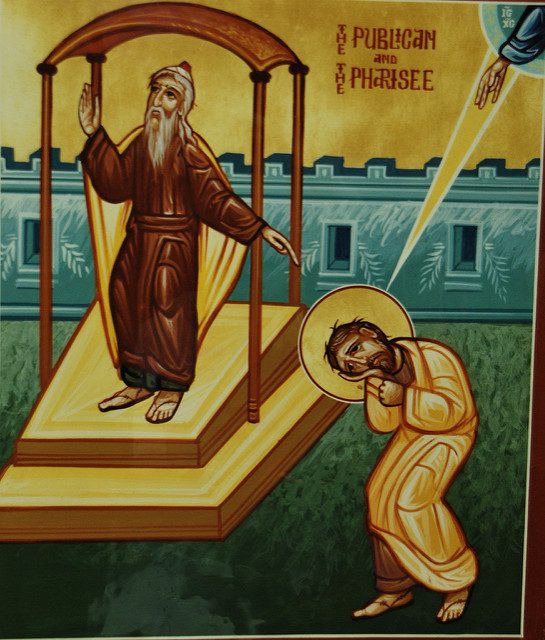

Moving from the realm of politics and social control, let’s apply this distinction to the Christian life. Perhaps it can help us to see the difference between Pharisaism and legitimate moral critique.

It would seem that “moralizing” comes from the perspective of moral superiority. It includes the sense of “self-righteousness.” Thus we have Christ’s warnings:

“Judge not, that you be not judged. For with the judgment you pronounce you will be judged, and with the measure you use it will be measured to you. Why do you see the speck that is in your brother’s eye, but do not notice the log that is in your own eye? Or how can you say to your brother, ‘Let me take the speck out of your eye,’ when there is the log in your own eye? You hypocrite, first take the log out of your own eye, and then you will see clearly to take the speck out of your brother’s eye. (Matthew 7:1-5)

The problem with “judging” in this context is that we will be judged by the same standards we use to judge others. Can we really bear that?

“Being moral,” according to Mr. Davidson, “is about changing the way you act and actually helping others.” This is in line with Luther’s point that a good work–in contrast to the attempts to accrue merit by the isolated exercises of the monastery–is one that actually helps someone. Luther’s ethic, in his theology of vocation, is built around loving and serving your neighbor.

Jesus here supports the action of taking the speck out of your brother’s eye. It’s just that your own “log” can prevent you from helping your brother effectively.

Being moral would seem to communicate your concern for the person and for the people who are hurt by the bad behavior.

For example, pro-lifers are “being moral” when their focus is on saving the lives of unborn children. It would be possible to “moralize” the issue, I suppose, by simply demonizing women who get an abortion, but I can’t remember ever seeing that in pro-life circles.

To be sure, parents, teachers, police officers, etc., must sometimes “change the way other people act—by force if necessary.” But this is their vocation.

Back to Wordsworth’s “Ode to Duty,” the poet does not simply lambaste people for not doing their duty. He writes about his own failures to do so, brings out the unexpected beauty of duty–personified as “stern daughter of the voice of God”–and shows how following the objective demands of duty is far more helpful than being blown about by subjective impulses. The poet is self-deprecating and writes to help his readers. Thus, a poem on “Duty”–a quality we almost never hear about today, except in the military, where “duty” still holds a place of the highest honor–is not a moralizing harangue but a moral exhortation.

Illustration, Icon of the Pharisee and the Publican Icon [Luke 18:9-14] via Ted, Flickr, CC0, Creative Commons License