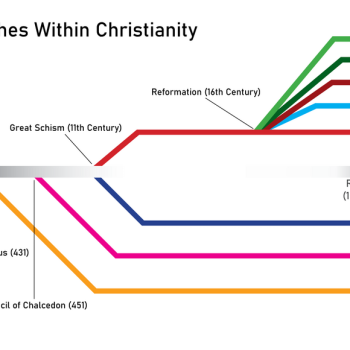

Luther’s theology of culture, his doctrine of the Two Kingdoms, is often associated with or even identified with St. Augustine’s notion of the Two Cities. But, actually, it would be closer to the truth to see them as opposites.

In his magisterial treatise The City of God, Augustine defines the City of Man and the City of God in terms of two loves: the love of self and the love of God. The City of Man, dominated by self-love, is intrinsically sinful. The City of God, consisting of the Church on earth and in Heaven, is righteous. The two cities are thus in conflict with one another.

Luther’s two loves, on the other hand, are the love of God (the spiritual kingdom) and the love of neighbor (the temporal kingdom). Both realms are ruled by God. The temporal kingdom–physical reality, social life, our bodily existence, etc.–is God’s creation. God governs and cares for His created order differently than He does His spiritual kingdom, but both belong to Him and are objects of His love. Christians are citizens of both kingdoms: receiving God’s love and loving God through faith in Christ; and loving and serving their neighbors in their various vocations (in the family, the workplace, the church, and the state), through which God Himself is also at work.

For Luther, the temporal kingdom is where Christians do good works, struggle against sin, bear their crosses, exercise their faith, and live out their Christian lives. The spiritual kingdom is that of the Gospel, in which Christians find the forgiveness of their sins and the gift of faith through Word and Sacrament, set apart for a salvation that will be eternal.

Luther’s doctrine of the Two Kingdoms is thus not dualistic, as is often charged, but integrative of the supernatural realm and ordinary life.

Augustine’s Two Cities, on the other hand, are dualistic. The dichotomy between the City of Man and the City of God would manifest itself in monasticism. To truly serve God to the fullest, it was believed that one should leave behind the City of Man– with its sexual desires, economic responsibilities, and worldly authorities–to inhabit permanently the City of God, which one did by taking the vows of celibacy, poverty, and churchly obedience.

Luther’s doctrine of vocation stressed that we are to live for God, not by abandoning the world, but by obeying Him in loving our neighbors in the world. Luther stressed that God uses this physical, created world (water, bread, wine, imprinted words on paper, parents, pastors) to bring us creatures to Himself. Luther thus values creation more than Augustine does, who, in the Confessions, feels guilty when he enjoys the taste of food or the beauty of the hymns in church, worrying that he is loving the creatures whereas all of his love should go to the Creator. You don’t find that kind of asceticism in Luther. Augustine, though, was a Platonist, who minimized the value of the physical realm.

What about love of self in Luther? Luther does describe sin as a “turning in upon the self.” But this can be a problem both in the temporal realm of vocation, in which we insist on being served by our neighbors instead of serving them, and in the spiritual kingdom, in which we can lapse into the sin of idolatrous self-worship.

There is, though, a proper love of self, in which we want the best for ourselves, in both realms. In the spiritual realm, we desire to avoid eternal punishment and to attain eternal bliss. In the temporal realm, when we serve others, we do have our rewards. In our economic vocations, we are to love and serve our neighbors through our work, but this can usually co-exist with the laws of economics regarding our rational self-interests. (This paragraph represents my thoughts. I don’t know if they are a corollary Luther pursued.) At any rate, all of this fulfills the Law and the Prophets, that we should love God and love our neighbors as ourselves (Matthew 22:38-40).

These thoughts were occasioned by a reading group I belong to that discussed The City of God. But, as was pointed out in that discussion, Augustine was not really setting forth a theology of culture, though Medieval theologians would later take it that way. Rather, he was describing the conflict between sinful, self-centered Man and righteous, gracious God. As such, he has many helpful insights.

My point here is simply that, despite what Wikipedia says, Luther’s Doctrine of the Two Kingdoms is NOT to be confused with Augustine’s Two Cities.

Illustration: St. Augustine, from The Four Doctors of the Western Church, attributed to Gerard Seghers (17th century) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons