In the division of labor, different people do different kinds of work for each other, with each specialized task contributing to the common good. The division of labor, with the means of exchange between each division, is a basic concept of economics. For Plato, the division of labor is fundamental to society itself (The Republic, Book II). Theologically, the concept calls to mind vocation, the way God ordained human life so that we must all serve each other.

Kevin D. Williamson points out that the division of labor is necessary for life itself–on the cellular level–and goes on to apply the concept to our current cultural struggles. From “The Division of Labor Is the Meaning of Life,” in National Review:

I would like you to entertain, for a moment, an idea that might sound a little eccentric, or maybe as plain and obvious as a thing can be. It is this:

The division of labor is the meaning of life.

I do not mean this metaphorically or analogically, but literally.

Life begins with the cell, and the cell is defined by a minimum of specialization: membrane, cytoplasm, and (usually) nucleus.

What makes a cell a living cell is a matter of some slight imprecision: Most living cells reproduce, but some (such as neurons) do not; most cells have nuclei and DNA, but mature red blood cells do not; etc. But the generally shared characteristics of living cells all depend upon the division of labor within the cell: order, sensitivity to stimuli, growth and reproduction, maintenance of homeostasis, and metabolism.

The cell is defined by the division of labor among the organelles and other cellular constituents. That gets us to the single-celled organism. Next comes division of labor among cells rather than within them. When cells begin to divide labor among themselves, they form tissues and organs, which in turn divide labor to produce organ systems and, ultimately, complex organisms.

Williamson then points out that human beings cannot function in isolation, that we need other people. And that the consequent social structures we inhabit–the family, the community, the nation–involve different kinds of divisions of labor.

In 21st-century human society, the mode of social life is so closely identified with the particularities of the division of labor that the two are practically identical. Even many of the so-called social issues are ultimately questions of the division of labor, for instance within marriage and family life, where changing attitudes toward sex (gender is a grammatical term) in relation to marriage, child-rearing, homosexuality, and other questions challenge ancient divisions of labor between men and women.

Which is to say, changes in the division of labor are by necessity changes in the mode of social life; radical, far-reaching, and sudden changes in the division of labor are, in the favorite term of Silicon Valley, “disruptive.”

He then takes us on a tour of history–the Roman Empire and its fall, the rise of feudalism, the Renaissance and the advent of capitalism–showing how this plays out, lauding the effects of global trade, commerce, and free markets while recognizing how culturally traumatic these can be.

His essay is extremely interesting, but I think that while he shows that the division of labor is essential to physical and social life, he stops short of his thesis, not showing how the division of labor is essential for the meaning of life. Questions of meaning bring us into the sphere of religion. What is missing in his analysis is the doctrine of vocation.

Williamson focuses on the Renaissance, with its flourishing of commercial trade, but he says almost nothing about the Reformation, beyond noting that the Protestant countries constituted the “new capitalist heartland.” But Luther’s doctrine of vocation played an important role in the economic and social developments he chronicles. (See my book Working for Our Neighbor: A Lutheran Primer on Vocation, Economics, and Ordinary Life.)

I would argue that pursuit of the division of labor, as in the pursuit of economic success, cannot give meaning to our lives–even though we instinctively look for it there–apart from a sense of vocation. That is, the realization that God works in and through the different vocations He calls us to in order to care for and to bless His creation. And the realization that we join in God’s work when we employ our vocation in love and service to our neighbors.

We have been taught that the purpose of our economic activity is to love and serve ourselves. Our self-interest is everything. I suspect that this view of free market capitalism looms behind the sense that it is somehow less moral than socialism (despite the manifest good that capitalism has done for the world). This also contributes to the guilt, the alienation, and the “is this all there is” feeling that can often be found among the economically successful.

But meaning can be found in serving others and in serving and being served by God Himself. And this happens precisely in the divisions of vocation.

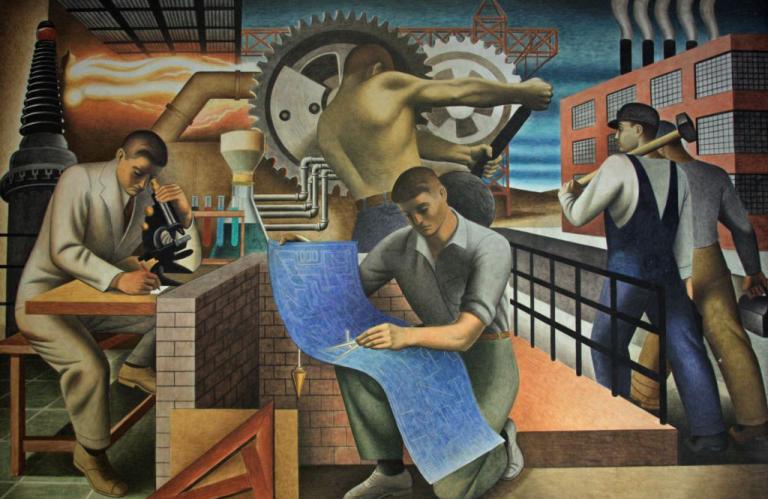

Illustration: Seymour Fogel, “The Wealth of the Nation” By Voice of America – http://www.insidevoa.com/content/historic-murals-at-voice-of-america/1364570.html, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=31996420