The popular TV shows used to portray blue collar workers. (Ralph Kramden the bus driver; Laverne and Shirley in the beer factory; Al Bundy selling shoes.) Today TV characters tend to be doctors, lawyers, psychologists, entertainers, office workers, and other white collar workers. So observes Jeff Haanen, who says that physical labor has fallen in cultural esteem and that the church needs to help restore the dignity of manual labor.

Haanen summarizes the book’s arguments:

The critical issue, says Cass, a policy expert affiliated with the right-leaning Manhattan Institute, is that we’ve prized consumption over production. We’ve built a larger “economic pie” and attempted to redistribute its benefits to those left out rather than build a labor market that allows the majority of workers to support strong families and communities.

Cass’s central idea is that “a labor market in which workers can support strong families and communities is the central determinant of long-term prosperity and should be the central focus of public policy.” Cass calls his big idea productive pluralism, the idea that “productive pursuits—whether in the market, the community, or the family—give people purpose, enable meaningful and fulfilling lives, and provide the basis for strong families and communities that foster economic success too.”

Cass offers some policy proposals as to how that might be done, for example, municipalities offering wage subsidies instead of tax breaks when they lure businesses and changing our educational system so that it does not privilege college careers and takes training in crafts and trades seriously.

Cass also criticizes the way that blue collar work is getting little respect:

“Waiters, truck drivers, retail clerks, plumbers, secretaries, and others all spend their days helping the people around them and fulfilling roles crucial to the community,” writes Cass. “They do hard, unglamorous work for limited pay to support themselves and their families.” Why shouldn’t we admire those who do harder jobs for lower wages on a broad scale? We’re capable of doing this with police officers, teachers, and firefighters. Why shouldn’t the work done by trash collectors, housekeepers, and janitors deserve the same degree of respect?

What especially struck me in Haanen’s review is his call for the church to play a role in restoring that respect.

I. . .wanted to hear more about the moral, emotional, and spiritual elements that make for both healthy laborers and healthy labor markets. Tim Carney’s Alienated America makes the case—from sociology, political science, and research, not theology—that local churches are the critical element in the renewal of America. If churches account for 50 percent of American civic life, as Robert Putnam famously pointed out in Bowling Alone, do they not also have a central role in reviving the fortunes of American workers, many of whom experience the pangs of meaninglessness and loneliness?

In a time when economic divides mask the growing dignity divide between professionals and the working class, between prestigious high-wage jobs and unspectacular low-wage jobs, the church can and must play a central role in reviving a vision for work.

I like Carney’s book, which tries to answer “Why Some Places Thrive While Others Collapse,” citing the problem of “failing social connections.” The author raises the question, “Should you be more worried about a church closing in your town than a factory closing?” and calls church “America’s Indispensable Institution.”

As for the church recovering the value of physical labor, this has to do, of course, with rediscovering the doctrine of vocation.

Ironically, some writers on the subject suggest that vocation only applies to “fulfilling” white collar careers, while the hard, painful ways of making a living are demeaning and meaningless. See, for example, this. Jeff Haanen himself raises the concern about those in the “faith and work” movement who neglect or even denigrate blue collar work, as I address here.

The Bible itself admonishes us “to work with your hands” (1 Thessalonians 4:11). As Haanen says,

Turning the other cheek, doing hard and dirty work, and being overlooked by the world—these are familiar notions to those of us who worship a carpenter and a washer of feet. Christians should join in Cass’s call to restore the dignity of work in America, rounding out his policy argument with the rich resources of our own tradition.

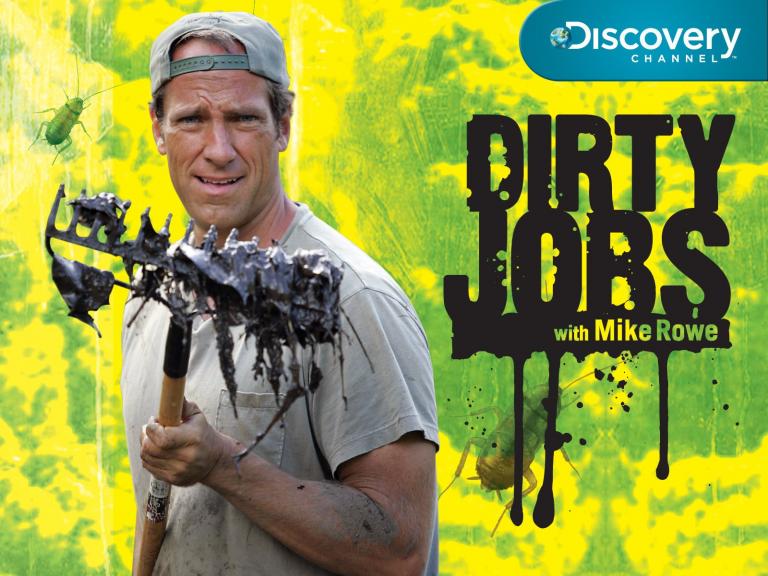

Another thing we can do is encourage the binge watching of Mike Rowe’s Dirty Jobs.

Image from Amazon.com