As Christians wrestle with the problems of holding onto the faith in a time of unbridled secularism, Roman Catholic political theory is coming back with a vengeance.

This is evident in the debate between Sohrab Ahmari and David French, with the Catholic Ahmari arguing that the culture and the government must be informed and shaped by the church, while the evangelical French argues that the church must work not for dominance but for liberal democracy and religious liberty.

Many Protestants are taking the side of Ahmari–a legitimate position, to be sure–but they would do well to be aware of how Catholic theology fits into these Christian political theories that are receiving more and more attention.

The Catholic political theory is called “integralism.” From the Wikipedia article:

In politics, integralism or integrism (French: Intégrisme) is the set of theoretical concepts and practical policies that advocate a fully integrated social and political order, based on converging patrimonial (inherited) political, cultural, religious, and national traditions of a particular state, or some other political entity. Some forms of integralism are focused on achieving political and social integration, and also national or ethnic unity, while others were more focused on achieving religious and cultural uniformity. In the political and social history of the 19th and 20th centuries, integralism was often related to traditionalist conservatism and similar political movements on the right wing of a political spectrum, but it was also adopted by various centrist movements as a tool of political, national and cultural integration.

As a traditionalist political movement, integralism emerged during the 19th and early 20th century polemics within the Catholic Church, especially in France. The term was used as an epithet to describe those who opposed the “modernists“, who had sought to create a synthesis between Christian theology and the liberal philosophy of secular modernity. Proponents of Catholic political integralism taught that all social and political action ought to be based on the Catholic faith. They rejected the separation of church and state, arguing that Catholicism should be the proclaimed religion of the state.

Contemporary discussions of integralism were renewed in 2014, with critiques of capitalism and liberalism.

Evangelicals too often speak of “integrating” the various spheres of life under a Christian worldview. And the article agrees that there can be a non-Catholic, even non-Christian, integralism. But Catholics are leading the charge.

Here is how the Catholic integralist Jonathan Culbreath explains the concept, from Catholic Integralism: The Only Viable Post-Liberal Political Theology:

Integralism begins with the first premise that it is the role of politics to direct human beings to their final end, the purpose for which they were created by God, their highest good — which is of course God himself. The end or purpose of human life is union with God, and political power directs humans to this end. But this end has two distinct but interrelated dimensions: a temporal dimension and an eternal dimension, or a natural and a supernatural dimension. To these two dimensions of the end, or the good, there correspond two dimensions of political power itself: a temporal power and and a spiritual power, or the State and the Church. These institutions have distinct but interrelated jurisdictions over matters directed to the two dimensions of the good. Consequently, they are obligated to cooperate towards the joint attainment of this end, in its two dimensions. It is obvious at this point that integralism is diametrically opposed to the classic liberal principle of the separation of Church and State, expressed in the First Amendment to the Constitution — which is just one application of the general liberal commitment to political neutrality. Integralism, unlike classical liberalism, adheres to an assertive and substantive vision of the political good, making no pretenses of a politics which abstains from such a vision.

Culbreath goes on to cite various “post-liberal” thinkers who are approaching this view, but he says that it can never be achieved apart from submission to the Roman Catholic Church. He concludes, “The embrace of integralism, and the subordination of states to the sole universal jurisdiction of the Catholic Church, is the solution to all of the problems which are facing liberals — and conservatives — not only in America, but globally.”

This political theology is traced back to the writings of the 5th century Pope Gelasius I, who wrote about how God governs the world by means of both a spiritual authority invested in the Pope and a temporal authority invested in the Emperor. The so-called “Gelasian Dyarchy” of Pope and Emperor has been a staple of Catholic political theology from the Middle Ages through the Counter-Reformation and afterwards.

And it continues in Catholic integralism. So says integralist Edmund Waldstein in his illuminating essay Integralism and Gelasian Dyarchy.

What would this look like today, if integralism as the solution to our political and social woes could be implemented?

The Pope we have today is Pope Francis, whom most integralists, being conservative Catholics, cannot abide. Would he really function as the moral and social authority that they crave?

And who would be Emperor? The presiding bureaucrat of the European Union, which would be the closest equivalent of the trans-national Holy Roman Empire? Surely the Gelasian Dyarchy would require someone who would apply temporal power more vigorously. Donald Trump might fit the part, but he is a nationalist and anti-globalist, working against what Patrick Buchanan criticized as the “American Empire.” Maybe a better candidate would be Vladimir Putin. “Czar” was the Russian rendition of “Caesar,” and Putin seems to be an embodiment of that kind of figure, who would love to rebuild the Russian, if not the Soviet, empire. But that would be an eastern empire, a Byzantine kind of revival, being Orthodox, not Catholic, and Eastern Orthodoxy cannot abide the papacy.

Most integralists today are nationalists. But empires, which their theory seems to require, are cosmopolitan and multi-national. Can there be an integralism based on Papacy and King, or Papacy and President? But this would mean a universal spiritual leader and a localized head of state.

Could both the spiritual and temporal authorities be localized? Would integralists countenance a national church, as was the practice in the early nation-states? But those were Protestant. (Great Britain had Anglicanism. Scandinavia and parts of Gerany had Lutheran state churches. America’s state church today, should one be started, would presumably be Evangelical.) Catholic nation-states may have had their kings, but, except for France, they tended to owe allegiance to the Holy Roman Emperor.

Nationalists sometimes forget that the nation-state is a modern innovation, like liberal Democracy. (Medieval Europe had no nations, as such, just feudal relationships that transcended ethnic and language identities. England’s Norman kings were French. Germany was a collection of principalities, not a unified nation at all until the 19th century.)

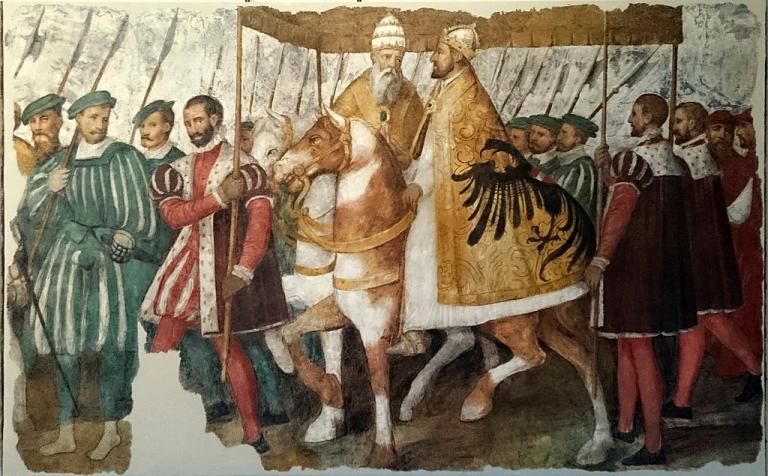

The problem is that integralism is theoretical and idealized. But history and government are particular and concrete. Governance by Pope and Emperor may sound like the ultimate means of promoting the common “good.” But the Popes may well be like the depraved Alexander VI or the liberal-minded Francis, rather than the integralist ideals. And the Emperor may well be like the actual Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V, who fought wars against the Pope.

Both the Pope and the Emperor opposed Luther and the Reformation, and vice versa. Notice that “integralism,” the notion that the social and political order should be integrated with the church, is the opposite position of Luther’s Two Kingdoms, which insists that the two realms should be distinguished from each other.

Lutherans, other Reformation Christians, Protestants in general, and non-Catholics of every stripe should be very cautious in accepting “integralism” as a way out of our social problems.

HT: My former student and fellow Patheos blogger John Ehrett, who offers a sophisticated Lutheran perspective on these issues. See his posts here, here, and here.

Image: “Pope Clement VII and Emperor Charles V [the Pope and Emperor during Luther’s Reformation] on horseback under a canopy,” by Jacopo Ligozzi via Wikimedia, Public domain.