“Hate” has become another all-purpose term of opprobrium, like “Nazi.” If you oppose someone for any reason, you are a “hater.” If you disapprove of some idea or practice, you “hate” the people who hold that idea or follow that practice. If you speak out about it, you may get accused of “hate-speech.” And yet, despite the inflation of the word’s meaning, there is such a thing as “hatred,” and we would do well to understand the emotion.

I came across a discussion of the psychology of hatred and how it is different from other negative emotions. Amanda Ripley sees it as facet of what is called “high conflict,” along with fear and anger. But whereas fear and anger can have positive effects, the same cannot be said of hatred.

In the context of her article, she is mainly discussing long-running, intractable wars, which become fueled by hatred–Arabs vs. Israelis, the civil wars in Sudan, Angola, etc.–but it applies also to our own conflicts, from our political polarization to the degeneration of relationships that can wreck marriages.

From Amanda Ripley, Americans are at each other’s throats. Here’s one way out:

The American people appear to be in a “high conflict,” which is a term of art among people who study conflict. A high conflict is one that feels existential and irresolvable, and it continues on its own momentum, even when specific problems could in fact be solved. . . .

“Once we are drawn in, they take control,” Coleman writes. “They tend to enrage us, trap us, frustrate us, drain us of energy and other critical resources, and seem to never go away no matter what we do.”

In high conflict, our brains behave differently. Emotions – specifically, fear, anger and hatred – matter more than all the leaked documents or congressional reports imaginable. . . .

Under certain circumstances, for example, anger can be useful. It can boost people’s support for reconciliation and for taking risks in peace talks. Angry people usually want to correct their opponents’ behavior. They still contemplate a future together on the same planet, which is something. Even fear can be managed; it still allows for compromises.

Hatred, though, is different. Hatred assumes the enemy is unchangeable. Irredeemable. Unimprovable. The goal of hatred, generally speaking, is not to correct; it’s to annihilate. Why correct someone who is inherently and immutably evil? Hatred, then, is an impediment to peace, Halperin says. It escalates and prolongs conflict, and it can motivate people to commit massacres.

No one in conflict wants to admit they feel hatred. “If you talk to Israelis and Palestinians, they will definitely agree that negative emotions are a problem,” Halperin says, “but it’s the problem of the other side.”

[Keep reading. . .]

The Bible says that we should “Hate evil, and love good” (Amos 5:15). And yet, we are not to hate even our enemies: “You have heard that it was said, ‘You shall love your neighbor and hate your enemy.’ But I say to you, Love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you” (Matthew 5:43-44). To be sure, Christians should expect to be hated, but they must not respond in kind. Rather, they should repay hatred with love:

“Blessed are you when people hate you and when they exclude you and revile you and spurn your name as evil, on account of the Son of Man! Rejoice in that day, and leap for joy, for behold, your reward is great in heaven; for so their fathers did to the prophets. . . .

I say to you who hear, Love your enemies, do good to those who hate you, bless those who curse you, pray for those who abuse you. . . .And as you wish that others would do to you, do so to them.

“If you love those who love you, what benefit is that to you? For even sinners love those who love them. 33 And if you do good to those who do good to you, what benefit is that to you? For even sinners do the same. . . .But love your enemies, and do good, and lend, expecting nothing in return, and your reward will be great, and you will be sons of the Most High, for he is kind to the ungrateful and the evil. Be merciful, even as your Father is merciful. [Luke 6: 22-23, 27, 31-33, 35)

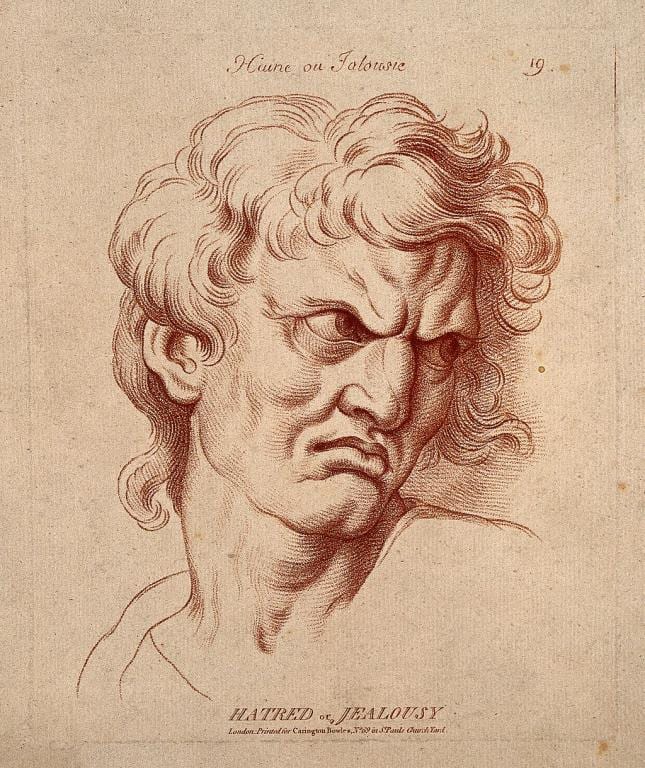

Illustration: “Hatred or Jealousy,” from Expressions of Emotions by Charles Le Brun (1619-1690) via Wikimedia Commons