We have quite a heritage of literature about plagues. The Italian author Boccaccio (1313–1375) wrote The Decameron, in which 10 people quarantine themselves from the Black Death and entertain themselves by telling stories. Daniel DaFoe, the author of Robinson Crusoe and one of the inventors of the novel, wrote the fictional A Journal of the Plague Year (1722). Stephen King’s The Stand (1978), about an influenza-like pandemic that wipes out much of the world’s population, is one of his best books. We could add filmmaker Ingmar Bergman’s The Seventh Seal with its Knight playing chess with Death as the Black Plague devastates the land.

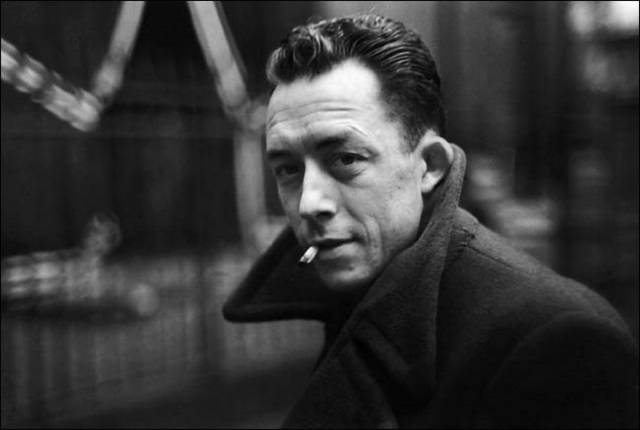

Such works can help us make sense of what is happening as we live through our epidemic. But the novel with the greatest applicability has to be Albert Camus’ The Plague (1947). The French novelist shows the reactions of different people when an epidemic hits a town in Algeria. Not only is the novel a realistic depiction of the impact of a plague on the way people think and behave, it also becomes a parable about the human condition.

The Australian theologian John Kleinig has written an article for a forthcoming issue of Logia: A Journal of Lutheran Theology on Psalm 91, about “the pestilence that stalks in darkness,” which we blogged about. In the article, he discusses Camus’ novel, which also quotes Psalm 91, even though the author was not a believer.

Here is what he had to say about the novel, quoted with the author’s permission:

In late 1946 the French author Albert Camus finished his famous novel “The Plague”. In it he gives an eerily accurate description of an epidemic that sweeps through Oran, a large port on the Algerian coast in North Africa.

He describes how a state of emergency was declared and martial law was enforced to curb the epidemic. Shops were shut down, travel was prohibited, isolation camps were set up, and baptisms and funerals were forbidden. Even though all this was ostensibly done to allay the fears of people, official misinformation and untruthful rumors infected them with fear and panic and selfish concern for personal safety at the expense of others. And that was worse than plague itself. In this story Camus shows how the plague was overcome by kindly medical care and statistical truthfulness.

I am surprised that Camus, an agnostic, repeatedly quotes from Psalm 91 in this novel. But I am even more surprised at his intimation that the worst effect of the virus is not the threat of physical infection or social isolation, but mental, emotional and spiritual infection with the fear of death. That stalking fear has infected us all in this epidemic; it is also one of the ways by which the devil attacks us (Heb 2:14-15).

In a subsequent exchange, Dr. Kleinig tells about Camus’ sequel to his novel, a play called The State of Siege:

After the huge success of this novel he wrote a play called “The State of Siege” in which he describes a totalitarian government that arises from the impact of the epidemic in the city of Cadiz. As far as I can remember, its dictator does not sit a throne but on an office chair; he does not rule but functions as an ordinary, bureaucratic way with the complicity of the citizens who desire safety and protection. His main strategy is to replace honest, personal discussion with officially sanctioned propaganda because unsanctioned words in face to face speech are the main carriers of infection.

What I got from The Plague in addition is that we are in this position even without an actual epidemic. People are dying all around us. We too will die eventually, though we do not know when or how. We respond to the reality of death primarily by not thinking about it. We fill our lives with distractions and trivialities to hide from ourselves the fact of our mortality. Camus’ point is the only townspeople who are living meaningful lives during the plague are those who face death head on, particularly by helping the sick and the dying.

Christians can agree with that. We need to realize that we will die, so that we can live our lives accordingly. The Law teaches us that we must die, which can turn our focus to the God who entered our plague-ridden world, who “took our illnesses and bore our diseases” (Matthew 8:17). That includes our moral and spiritual diseases. He died with us. And then He rose with us.

Do you not know that all of us who have been baptized into Christ Jesus were baptized into his death? We were buried therefore with him by baptism into death, in order that, just as Christ was raised from the dead by the glory of the Father, we too might walk in newness of life. (Romans 8:3-4)

And that newness of life involves loving and serving our neighbors, including the sick and the dying, which covers just about everybody.

Photo by Dietrich Liao via Flickr, Creative Commons 2.0 License,