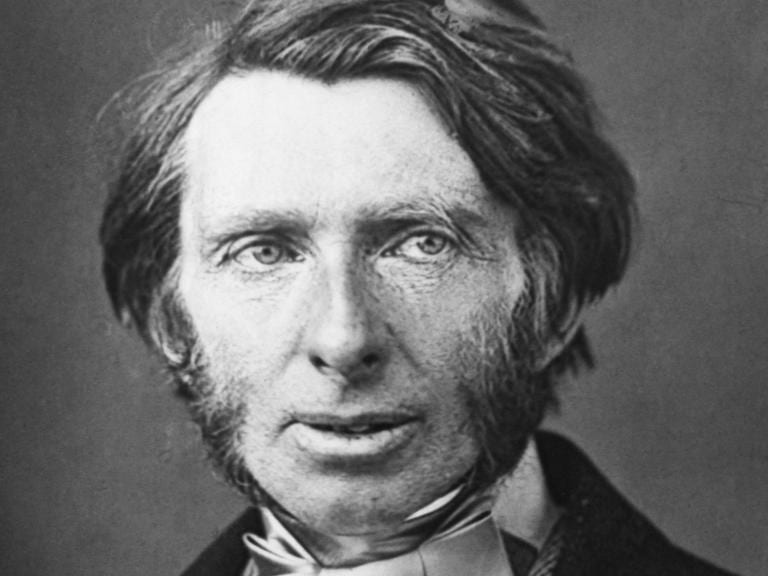

In his book that I blogged about, Defending Boyhood, Anthony Esolen discusses the masculine qualities that lead to the military virtues. He quotes the Victorian author John Ruskin on why we tend to admire soldiers more than “merchants.”

The quotation is from Ruskin’s 1862 book Unto This Last. He goes on to apply his principle to other occupations that we admire, and in doing so, makes some striking points about what we can recognize as the Reformation doctrine of vocation. I’ll discuss those, and then say a few words on behalf of “merchants.”

From John Ruskin, Unto This Last (free online):

For the soldier’s trade, verily and essentially, is not slaying, but being slain. This, without well knowing its own meaning, the world honours it for. A bravo’s trade is slaying; but the world has never respected bravos more than merchants: the reason it honours the soldier is, because he holds his life at the service of the State. Reckless he may be — fond of pleasure or of adventure-all kinds of bye-motives and mean impulses may have determined the choice of his profession, and may affect (to all appearance exclusively) his daily conduct in it; but our estimate of him is based on this ultimate fact — of which we are well assured — that put him in a fortress breach, with all the pleasures of the world behind him, and only death and his duty in front of him, he will keep his face to the front; and he knows that his choice may be put to him at any moment — and has beforehand taken his part — virtually takes such part continually — does, in reality, die daily.

From the soldier’s willingness to die out of a sense of service, Ruskin develops the concept of self-sacrifice, of being willing to deny oneself for a higher principle or for the good of someone else. He then addresses other professions that we admire: lawyers (OK, the Victorians evidently held that profession in greater esteem than is common today), physicians, and (quite rightly) clergymen:

Not less is the respect we pay to the lawyer and physician, founded ultimately on their self-sacrifice. Whatever the learning or acuteness of a great lawyer, our chief respect for him depends on our belief that, set in a judge’s seat, he will strive to judge justly, come of it what may. Could we suppose that he would take bribes, and use his acuteness and legal knowledge to give plausibility to iniquitous decisions, no degree of intellect would win for him our respect. Nothing will win it, short of our tacit conviction, that in all important acts of his life justice is first with him; his own interest, second.

In the case of a physician, the ground of the honour we render him is clearer still. Whatever his science, we would shrink from him in horror if we found him regard his patients merely as subjects to experiment upon; much more, if we found that, receiving bribes from persons interested in their deaths, he was using his best skill to give poison in the mask of medicine.

Finally, the principle holds with utmost clearness as it respects clergymen. No goodness of disposition will excuse want of science in a physician, or of shrewdness in an advocate; but a clergyman, even though his power of intellect be small, is respected on the presumed ground of his unselfishness and serviceableness.

All of this, of course, is the doctrine of vocation, that in every sphere of relationship or responsibility to which we have been called–in the workplace, the family, the church, and the society–we are to love and serve the neighbors who are brought into our lives by this calling. And love and service to our neighbor in vocation is our “living sacrifice,” an example of the cross bearing that our Lord calls us to: “If anyone would come after me, let him deny himself and take up his cross daily and follow me.”(Luke 9:23).

But what about the “merchant”–that is, people in the business world? Ruskin says that running a business takes just as much intelligence, personal skills, and leadership ability as is needed in the military, the legal profession, and the church. The difference, he concludes, is that people in business are perceived to be primarily self-interested:

Now, there can be no question but that the tact, foresight, decision, and other mental powers, required for the successful management of a large mercantile concern, if not such as could be compared with those of a great lawyer, general, or divine, would at least match the general conditions of mind required in the subordinate officers of a ship, or of a regiment, or in the curate of a country parish. If, therefore, all the efficient members of the so-called liberal professions are still, somehow, in public estimate of honour, preferred before the head of a commercial firm, the reason must lie deeper than in the measurement of their several powers of mind.

And the essential reason for such preference will he found to lie in the fact that the merchant is presumed to act always selfishly. His work may be very necessary to the community, but the motive of it is understood to be wholly personal. The merchant’s first object in all his dealings must be (the public believe) to get as much for himself, and leave as little to his neighbour (or customer) as possible.

In defense of all of you “merchants,” I would add, though, that people in business do serve their neighbors, often in self-sacrificial ways. Ruskin omits the aspect of vocation that teaches how God works through human beings in their various callings in order to bless and provide for His creation. Even the selfish merchant only interested in his profits is compelled to serve his neighbor. If the businesses doesn’t provide goods or services that help their customers, they will not stay in business very long.

The merchant serves his neighbor, whether or not he loves them. Likely, because of his sinful nature, he mainly loves himself. Faith in Christ bears fruit, though, in the love of neighbor. So the Christian merchant can carry out his vocation as an act of faith and love. The business still must make a profit or it will not last, but vocation can give it another dimension. And if Christians in business demonstrate a spirit of self-sacrificial love and service for their customers and their employees, they too will find themselves admired.

The same, of course, is true for soldiers, lawyers, clergymen, and every other vocation we look up to. (What would those be today? Not politicians, who have developed a reputation for selfishness and power-seeking, rather than public service. We admire athletes, though I’m not sure how Ruskin’s thesis applies to them. I suppose they sacrifice themselves in their physical discipline and for the sake of their team.) A soldier might serve his country without loving it, or give his life for his comrades without loving them, but the love gives his sacrifice a greater meaning. A pastor might serve his flock without loving them as he should, though this is something all Christians must grow in as their faith grows.

Here is how Ruskin summarizes his thoughts about vocation:

Five great intellectual professions, relating to daily necessities of life, have hitherto existed — three exist necessarily, in every civilised nation:

The Soldier’s profession is to defend it.

The Pastor’s to teach it.

The Physician’s to keep it in health.

The lawyer’s to enforce justice in it.

The Merchant’s to provide for it.

And the duty of all these men is, on due occasion, to die for it.

“On due occasion,” namely: –

The Soldier, rather than leave his post in battle.

The Physician, rather than leave his post in plague.

The Pastor, rather than teach Falsehood.

The lawyer, rather than countenance Injustice.

The Merchant–what is his “due occasion” of death?

It is the main question for the merchant, as for all of us. For, truly, the man who does not know when to die, does not know how to live.

Ruskin, by the way, often applies Christian ideas in fresh and unexpected ways. In my book Painters of Faith, I discuss and apply Ruskin’s view that aesthetics–what we find beautiful–is an intimation of the qualities of God, since, he said, ultimately, we can find pleasure in no one but Him. Thus, evocations of infinity are sublime and give us pleasure–because God is infinite. Works of art that combine unity and complexity are beautiful–because the Triune God is both complex and unified. (Painters of Faith is selling on Amazon for $59, but my daughter is selling them, through a coupon code she is offering, for just $18!)

Photograph: John Ruskin by W. & D. Downey / Public domain via Wikimedia Commons [detail]