We’ve been discussing justification and the atonement, criticizing the way so many Christians today are drawing back from these teachings.

One reason for that, though, is that advocates of these teachings often present them in an overly abstract way, as if God were only a philosophical collection of attributes that are in conflict with each other and that are in need of resolution. This is a kind of theological rationalism that presents God as an intellectual concept rather than as an infinite Person. As J. G. Hamann says, in the soon-to-be-released translation of the London Writings that I have been working on with translator John Kleinig, God does not want to be known merely through His attributes, but through His Word, in which He addresses us person-to-person.

In that treatment of Penal Substitution in Wikipedia that I referred to in our last post, the author describes the nuances of how Luther approached these mysteries:

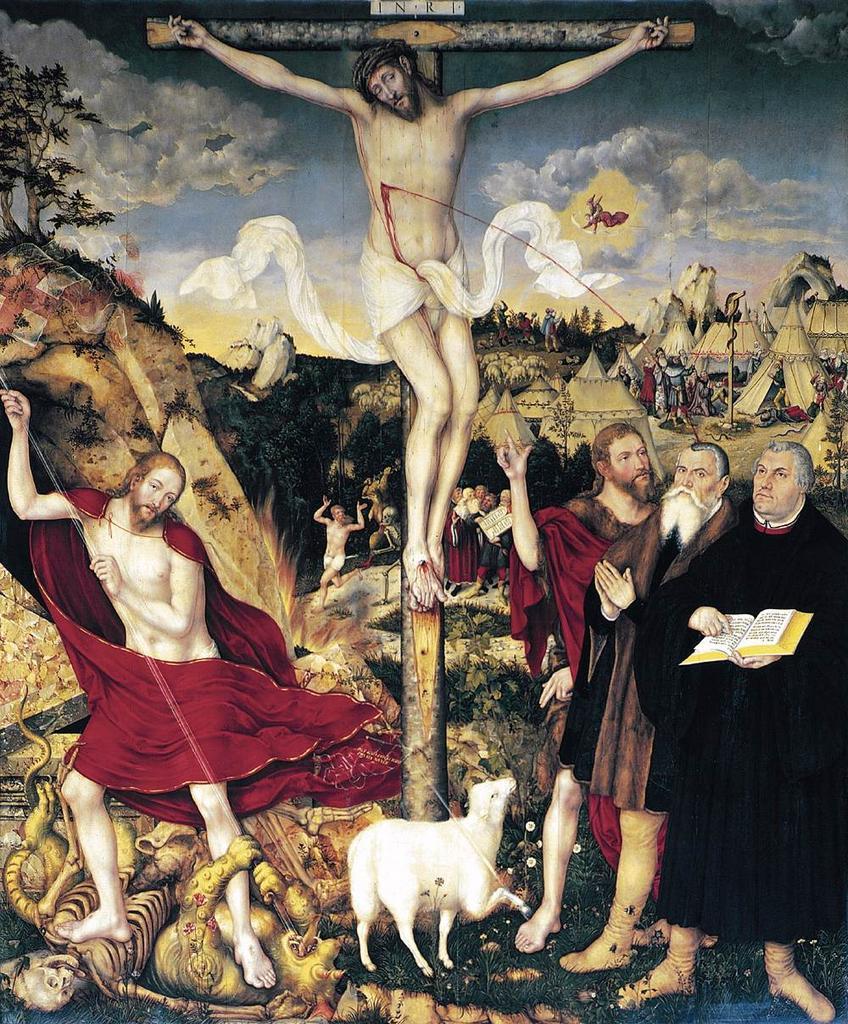

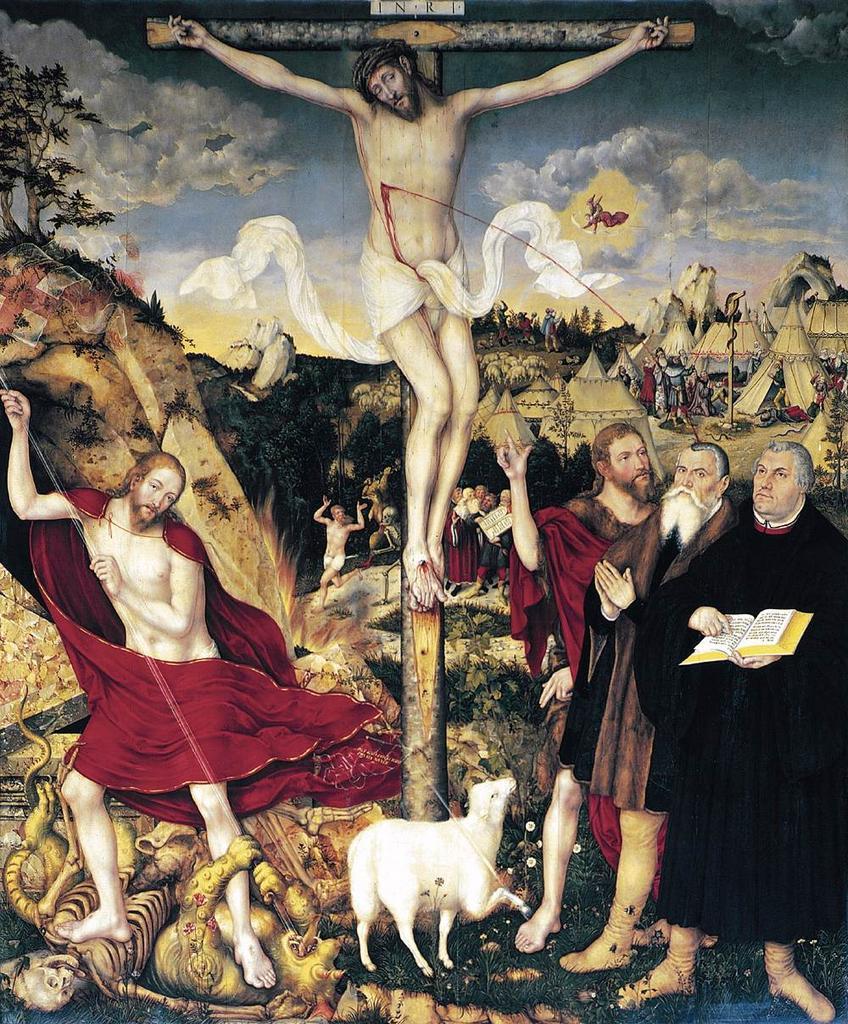

Broadly speaking, Martin Luther followed Anselm, thus remaining mainly in the “Latin” model identified by Gustaf Aulén. He held, however, that Christ’s atoning work encompassed both his active and passive obedience to the law: as the perfectly innocent God-man, he fulfilled the law perfectly during his life and, in his death on the cross, bore the eternal punishment that all men deserved for their breaking the law. Unlike Anselm, Luther thus combines both satisfaction and punishment.[42] Furthermore, Luther rejected the fundamentally legalistic character of Anselm’s paradigm in terms of an understanding of the Cross in the more personal terms of an actual conflict between the wrath of God at the sinner and the love of God for the same sinner.[43] For Luther this conflict was real, personal, dynamic and not merely forensic or analogical.[44] If Anselm conceived of the Cross in terms a forensic duel between Christ’s identification with humanity and the infinite value and majesty of his divine person, Luther perceived the Cross as a new Götterdammerung, a dramatic, definitive struggle between the divine attributes of God’s implacable righteousness against the sinful humanity and inscrutable identification with this same helpless humanity which gave birth to a New Creation, whose undeniable reality could only be glimpsed through faith and whose invincible power worked only through love. One cannot understand the unique character or force of Luther’s and the Lutheran understanding of the Cross apart from this dramatic character which is not readily translated into or expressed through the more rational philosophical categories of dogmatic theology, even when these categories are those of Lutheran Orthodoxy itself.

Lucas Cranach the Younger, Weimar Altarpiece via Snappygoat.com, public domain