Vox–the progressive, trendy online magazine–has been running a series of articles on forgiveness.

The editors start with the recognition that cancel culture, social media outrage, exposing the faults of great Americans, and the overall climate of indignation are causing problems of social cohesion. And that individuals who have become demonized, sometimes for transgressions they have committed decades ago, lack a way to become accepted back into society. So they asked various writers to discuss ways forward.

The various titles in the series are worth reading, but they reflect the difficulty of the task:

When justice isn’t served, how do we find forgiveness?

The Promise–and Problem–of Restorative Justice

As long as the fixation is on justice, you will never come to forgiveness. Justice means giving people what they deserve. Though greatly to be wished, justice is the opposite of forgiveness. The question is what to do when someone has been unjust but now seeks to be restored. That is hard for these experts to come to grips with.

One essay, though, does grapple with the real issues and is particularly revealing. Vox staff writer Aja Romana contributed Everyone Wants Forgiveness but No One Is Being Forgiven. As she wrestles with the problems that come from lacking any mechanism for forgiving and being forgiven, she never so much as mentions religion. But she uses religious–even theological–language.

It isn’t enough to simply say “I’m sorry,” she recognizes. There needs to be some kind of atonement:

If we applied a positive road map to a typical outrage cycle, what we would hope to find after that initial period of outrage is discussion, apology, atonement, and forgiveness. That process almost never happens on the modern public stage. . . .

While plenty of research has been done on the perfect apology, we’ve had very few cultural examples of one being delivered effectively and sincerely. We’ve had even fewer examples of such an apology being followed up with a process of actual atonement.

Forgiveness, she recognizes, requires some kind of grace:

Most moral and spiritual authorities teach us that the cycle of repentance usually involves grace. Grace, the act of allowing people room to be human and make mistakes while still loving them and valuing them, might be the holiest, most precious concept of all in this conversation about right and wrong, penance and reform — but it’s the one that almost never gets discussed.

That’s understandable. Grace relies on some huge assumptions: that people mean well and that their intent is not to be hurtful; that they are capable of self-reflection and change; and, of course, that we all possess equal shares of dignity and humanity. . . .

That’s what makes the concept of grace so powerful. It forces us to contend not only with other people’s human frailty but with our own: to remember how good it feels when someone, out of the blue, treats us with respect, empathy, and kindness in the middle of an angry conversation where we expect nothing but hostility. To be shown the kindness of strangers when we expect cruelty, and then bestow that gift in turn — that’s the remarkable quality of grace. But there’s little room for it when we’re barely able to handle the concept of forgiveness, and equally unable to stop being angry with the offender after all is said and done.

And so, we arrive back at the beginning of the cycle: We hang on to our anger, and all of this anger puts the possibility of grace even further out of reach.

The writer sees that forgiveness requires atonement and grace, but, in her secularist perspective, she can’t really find them. Atonement, she assumes, is something that transgressors have to do for themselves. But having to atone for one’s own sins becomes identical with punishment. The sinner must pay for his transgressions, if not in prison, by losing his job or being socially ostracized. The writer suggests that this payment should be made voluntarily, which would make it possible to forgive the sinner. But the thread of forgiveness is lost, and we are back to retributive justice.

As for grace, she is coming closer, but she assumes that grace is something that the transgressor must earn. (“That people mean well,” “that they are capable of self-reflection and change,” etc.) Thinking of what people deserve is not grace. We are back to justice.

So, of course, atonement “almost never happens,” and “all of this anger puts the possibility of grace even further out of reach.”

But what if there is an atonement and a grace outside ourselves? What if these are not subjective or self-manufactured qualities, but objective realities? What if God Himself atoned for us? What if we are objects not of other people’s grace but of God’s grace?

Then we would find actual forgiveness and have a basis for forgiving others.

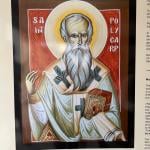

This is what Holy Week is all about. . . .