Mark Tooley, an evangelical Methodist who heads the Institute for Religion and Democracy, is in basic agreement with the statement until it gets to “Where a Christian majority exists, public life should be rooted in Christianity. . . .” In an article for Law & Liberty entitled

A National Conservative Faith?, he asks,

Does this section call for the state establishment of Christianity? It does not say so explicitly but arguably implies it. What does it mean for “public life” to be rooted in Christianity? What does it mean for the state to “honor” Christianity’s paramountcy? How should non-Christian private institutions “honor” Christianity? Is this expectation to honor Christianity mandated by law or upheld by social custom? If Jews and other non-Christians are “protected” to practice their faith in their own communities, is their religion then subordinated in public life by law or by custom? And if adults are protected from “religious or ideological coercion” in their private lives, are their public lives potentially subject to coercion, legal or social, in favor of Christianity?

Tooley is also concerned with the phrase “where a Christian majority exists.” Already the percentage of citizens who consider themselves Christians has dipped below 50% in many of the nations of Europe. In the United States, the percentage of self-identified Christians has declined over the last decade from 75% to 63%. He asks, “Does the calculus about rooting national public life in Christianity suddenly shift if self-identified Christians drop to 49 percent or less, which is possible in America and likely in most Western European nations?”

Tooley goes over the Founders’ discussions of the difference between religious “toleration,” which assumes an established religion, and the much stronger “free exercise of religion.” In that climate that promoted religious liberty, as opposed to a religious establishment promoted by the government, Christianity thrived. He concludes,

Incorporating Christianity specifically into a political manifesto, especially in America, is vexing. For two centuries, religion in America has not rested on state power. Its vitality, and its failures, are its own doing. Any revival of Christianity in America, or anywhere, depends on persons and communities, apart from government, seeking God through faith, prayer, and a thirst for holiness, with acts of mercy and love.

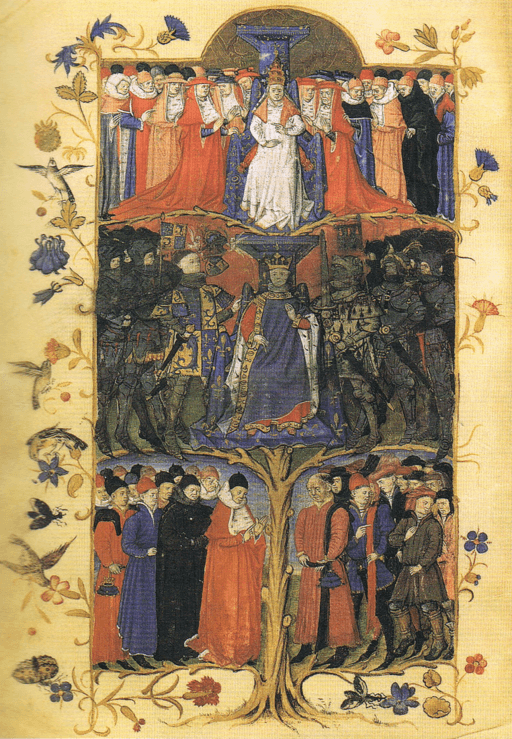

Article 4 of the National Conservatism statement reflects the integralism of several of its drafters and signers, who wish to recover the political sovereignty of the Roman Catholic Church over earthly governments. I would like to remind them that nation-states, as such, did not exist during the Middle Ages, a time of multi-national feudal obligations and the Holy Roman Empire. Rather, nation-states were one by-product of the Reformation. Yes, some of those nation-states also had their national churches, which would seem to be necessary for the implementation of Article 4, but that approach has led largely to the secularization of much of Europe, whereas religious liberty has led to the robust religious climate that has characterized the United States, at least till recently.

Just as the government should be limited so that it does not presume to control our economy or our personal lives, it should not presume to control our religious beliefs.

Though national conservatism seems to have much to commend it, my concern is that its emphasis on national culture might lend itself to the establishment of a divinized state, the promotion of cultural Christianity, and the secularization of the church.

Illustration: The traditional social stratification of the Occident in the 15th century, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons