Yesterday we posted about revenge, focusing on an article by Lauren Blumenfeld, who makes the case that revenge has come back to our political and cultural life with a vengeance, so to speak.

There are some other aspects of revenge, though, that she doesn’t seem to get into. I wrote my Master’s Thesis on Seventeenth Century revenge tragedies, of which Hamlet is the most famous, though there were lots of them. I argued that these plays often show a tension within them between the passions that call for revenge and the knowledge that personal revenge is forbidden by God. Behind this tension, though, is the legitimate need for justice, which is often achieved in these plays through God’s providence.

In the course of this project, I did quite a bit of research into the nature of revenge. I learned that tribal societies, lacking an overarching central government with a legal system, deal with wrongdoing through elaborate systems of revenge. If a member of your tribe–or your family–is killed by a member of another tribe, or family, you–or a designated family member–must take revenge.

The problem with this system is that the other tribe will now take revenge against your tribe, whereupon you take revenge for that, and so on infinitum. The result is “feuds” that can go on for generations. Inter-tribal warfare, which plays a major cultural role in many tribes, often began with an action that provoked revenge, which escalated into a vendetta and then to total war.

Because revenge could be so destructive, ways to put a stop or a limit to the cycle of violence also developed, such as paying a sum of money or the equivalent to the injured party, called in the Germanic tribes the wergeld, or “man price.”

But this tribal way of administering rough justice could be resolved only with a higher form of government. This is illustrated in the Greek myth of Orestes, as portrayed by Aeschylus in his trilogy of revenge plays known as the Oresteia. The series depicts a horrendously bloody revenge cycle within a family, no less, which comes to an end when Athena, the goddess of wisdom, intervenes and sets up a trial of the offenders. She then ordains that no more may individuals take revenge themselves against a wrongdoer. Rather, the cases must be tried and, if need be, punished, under a rule of law. Athena is thus depicted as the founder of Athenian government, which brings justice, as opposed to the Greek’s earlier tribal revenge codes.

That’s a symbolic working out of the problem, of course, but it happened historically, as well. King Alfred the Great unified the Saxon tribes in England by claiming the role of avenger for himself and his court, in that he would collect the wergeld and give it to the injured families, so that they did not need to launch a destructive vendetta. He also introduced a system of laws, thus creating the nation of England.

The Bible, though, gives us the most ancient resolution and became the model for other nations. Ancient Israel was a tribal society (as in, the 12 tribes of Israel), and it practiced revenge. The Mosaic law limited revenge. (Donald Trump’s favorite verse, “An eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth” [Leviticus 4:17-24], was a formula for just retaliation, as opposed to the murders that had become commonplace for slights of honor. Taking a life deserved the death penalty, but not knocking out a tooth.)

More significantly, the Levitical Law provided for “cities of refuge” when the promised land would be settled, where a “manslayer” could flee from the avenger (Numbers 35; Deuteronomy 19). The elders of the city then conducted a trial. They would then determine if the killing were accidental or premeditated; that is, they looked at intent. If they found that the manslayer did not intend for the victim to die, he could stay in the city and be protected from the avenger. If the manslayer planned the killing–something that had to be established by more than one witness (note the rules for a fair trial)–he must pay for the murder with his life. In a concession to the old code, he would be turned over to the avenger, who would act as the executioner.

The New Testament speaks clearly to both the moral and the legal issues. Romans 12 could hardly be clearer in condemning revenge:

17 Repay no one evil for evil, but give thought to do what is honorable in the sight of all. 18 If possible, so far as it depends on you, live peaceably with all. 19 Beloved, never avenge yourselves, but leave it to the wrath of God, for it is written, “Vengeance is mine, I will repay, says the Lord.”20 To the contrary, “if your enemy is hungry, feed him; if he is thirsty, give him something to drink; for by so doing you will heap burning coals on his head.” 21 Do not be overcome by evil, but overcome evil with good. (Romans 12:17-21)

This rules out personal revenge completely. But God in His wrath against evildoers will repay. He is the source of justice, not our passions and resentments. We do not need to take the burden of punishing evildoers on ourselves. He is the avenger, not we ourselves.

And then, in the very next verses, which we often separate because of the chapter division, we learn one facet of how God executes justice:

13 Let every person be subject to the governing authorities. For there is no authority except from God, and those that exist have been instituted by God. 2 Therefore whoever resists the authorities resists what God has appointed, and those who resist will incur judgment. 3 For rulers are not a terror to good conduct, but to bad. Would you have no fear of the one who is in authority? Then do what is good, and you will receive his approval, 4 for he is God’s servant for your good. But if you do wrong, be afraid, for he does not bear the sword in vain. For he is the servant of God, an avenger who carries out God’s wrath on the wrongdoer. (Romans 13:1-4).

That is to say, we must not take revenge because vengeance belongs to God and His wrath, which is exercised, in this world, by the governing authorities. The earthly magistrate is “an avenger,” who “carries out God’s wrath on the wrongdoer.” God is taking the revenge, which we must not take ourselves, and He does so by means of the earthly magistrate. This is another example of the doctrine of vocation, in which God works through and by means of human beings.

This is the supreme precedent and command for a rule of law, with a government and criminal justice system, as opposed to the rule of personal retaliation.

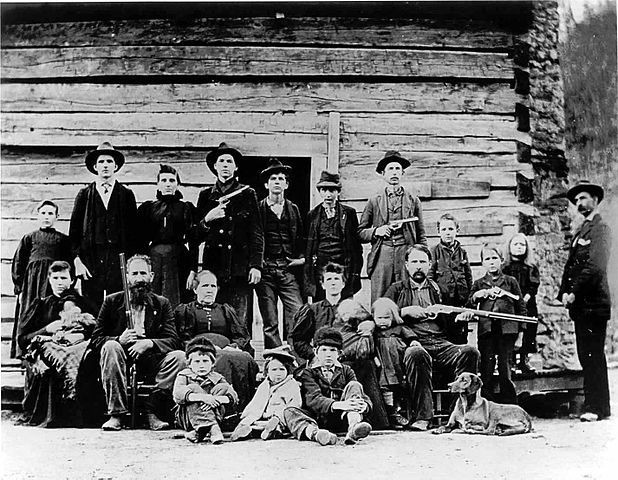

To be sure, people often revert back to the tribal revenge code in the absence of a government. People in remote areas for whom the government is far away often “take the law into their own hands,” even when this results in cycles of feuds and vendettas. Think of the Hatfields and the McCoys. Sometimes people who do not recognize the authority of the government because they consider it harmful to them make similar reversions. Gang killings in American cities often have the motivation of revenge, including for slights against a gang’s honor.

If revenge is coming back to the mainstream, as Blumenfeld says, though perhaps in the more genteel form of political retaliation or trying to get someone fired, this may be a symptom of our overall distrust in government and lack of confidence that the rule of law will bring justice. The Left has long attacked the government and sees the police as a tool of oppression. The Right too, in its suspicion of big government and its intrusions, doesn’t think much of government authorities. Indeed, part of the problem is that the government authorities often fail to act as they should. Combine this with an intellectual climate that reduces all authority to the exercise of oppressive power, of course revenge will come to the surface again.

But we need to remember how dangerous this is. Far better to “repay no one evil for evil,” and to leave the payback to God, who alone can act with full righteousness, with the correct measure of justice and mercy, both in this world and in the next.

Photo: The Hatfield Clan in 1897, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=632843