Today is Epiphany, commemorating the Wise Men’s visit to baby Jesus, which begins a season of the church year in which the Bible readings in the lectionary focus on revelations of who Christ is: His presentation in the Temple, His Baptism, His first miracle, His calling of the disciples, etc., depending on the number of Sundays in any given year, culminating in His transfiguration. After that high point comes Lent.

The word “epiphany” means basically “the light dawns,” thus the imagery in Epiphany hymns of light appearing in darkness, as in the Wise Men’s star.

About the Wise Men. . . .This time of year, especially in the leadup to Christmas, a lot of articles, posts, and documentaries show up speculating about these gentlemen. We are told that we don’t know exactly who they were or where they came from, whereupon speculations are offered. We are told that we don’t know how many they were, the traditional number of three coming from their three gifts. We get expositions of the word “magi”: were they magicians? astrologers? Surely not! And, despite the crowns they wear in nativity scenes and despite that Christmas carol about them, they most emphatically were not kings!

Wondering about the historical details is fine, but it sometimes misses the point.

Before I go to that point, I’ve got to share with you a different historical take that I hadn’t heard of before and that makes a lot of sense. This is from Michael Simone, writing in the Jesuit magazine America, in an article entitled What can we learn from the Wise Men?

Matthew writes a more complex story than most people today realize. He would have known that the word magi, although it could have many meanings, primarily described the educated courtiers of the Parthian empire, which lay to the east of Judea. He would have also known that Herod and the Parthians had an uneasy history. The Parthians invaded Judea—and all of the eastern Roman Empire—in the year 40 B.C. They were driven out, but not before Herod used the chaos of the Parthian wars to seize the throne of Judea. The Parthians never gave up hope of conquering Judea, and Herod never felt fully confident on his throne as long as these powerful foreigners saw him as a Roman puppet.

Now, Matthew tells us, Parthian ambassadors have appeared in Jerusalem asking about a new king. Matthew certainly knew that this would have thrown Herod into a fury. Herod would have thought the Magi were establishing a usurper, around whom to rally opposition to his rule. His reaction, to kill every young male child in Bethlehem, is understandable in this context. What Matthew presents, then, is a story of Jesus caught up in a geopolitical struggle that threatens his very life.

What we can learn from this, according to Rev. Simone, is that “The story of the Magi reminds us that human machinations are flimsy affairs and that Christ has long practice in foiling them. No matter what motives the world and its rulers employ, all things ultimately—even unwittingly—come to pay homage to Christ.” True!

A full account of the Wise Men and how they have been portrayed in Christian iconography needs to consider not only Matthew 2 but Isaiah 60. This text begins with a prophecy of the Messiah that is a staple of the Christmas season:

Arise, shine, for your light has come,

and the glory of the Lord has risen upon you.

2 For behold, darkness shall cover the earth,

and thick darkness the peoples;

but the Lord will arise upon you,

and his glory will be seen upon you.

3 And nations shall come to your light,

and kings to the brightness of your rising.

The prophesy that “kings” shall come “to the brightness of your rising” is surely the source of the notion that “the wise men from the east” were kings. Especially in light of the imagery that comes next:

Lift up your eyes all around, and see;

they all gather together, they come to you;

your sons shall come from afar,

and your daughters shall be carried on the hip.

5 Then you shall see and be radiant;

your heart shall thrill and exult,[a]

because the abundance of the sea shall be turned to you,

the wealth of the nations shall come to you.

6 A multitude of camels shall cover you,

the young camels of Midian and Ephah;

all those from Sheba shall come.

They shall bring gold and frankincense,

and shall bring good news, the praises of the Lord.

This text–with its remarkable point of view account of how the Christ will feel when the nations come to Him– is at the heart of the great Epiphany hymn by Martin Opitz, Arise and Shine in Splendor. The reference to gold and frankincense can only call to mind the Wise Men, and the reference to “young camels” is doubtless the reason why our nativity scenes include them.

In the next verse, Isaiah 60 even alludes to shepherds:

All the flocks of Kedar shall be gathered to you;

the rams of Nebaioth shall minister to you;

they shall come up with acceptance on my altar,

and I will beautify my beautiful house.

That the portrayals of the Wise Men are shaped by this prophetic Biblical text certainly does not mean that they were not historical. Nor does it mean that Isaiah 60 is prophesying the Wise Men, or that they were actually kings after all. The prophet is describing a much larger truth, as multitudes of people come to Him, bringing their little children, and the whole world glorifies the Christ in their offerings and devotion. That prophecy is fulfilled first when the “good news” is extended beyond Israel to all nations, and it will be fulfilled ultimately at His return.

But the Wise Men offering their gifts is a foreshadowing of this reality and a reminder of it. The Nativity scenes are depicting not just what happened at the manger, but also what it means. The embellishments, such as putting crowns on the heads of the magi, are references to that other Bible passage in Isaiah 60. That these Parthians, or whoever they were, are depicted as “kings” makes clear the meaning of the event: Christ is for them, as well as the Jews. “Nations shall come to your light,/ and kings to the brightness of your rising.”

The iconography brings together multiple Biblical texts: Matthew 2 (the Wise Men), Luke 2 (the shepherds), and Isaiah 60 (the prophecy of Christ and the nations).

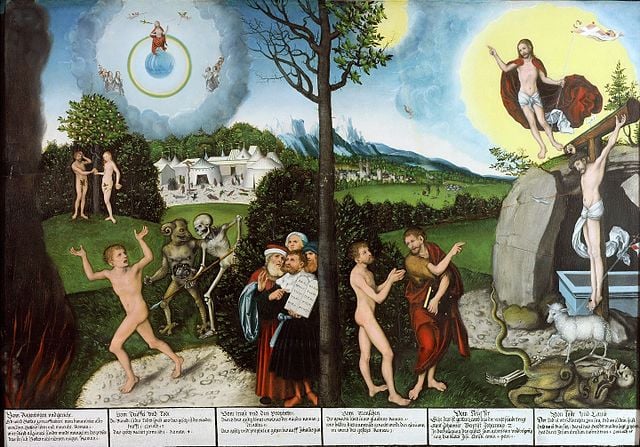

This brings up how Christian iconography depicts narrative. Instead of showing one moment frozen out of time, early Christian art shows time unfolding by giving multiple events from the story in one visual image. That is, instead of showing an event from the point of view of someone in the story, it presents an eternal point of view, which sees all of time simultaneously.

Thus, in the icon pictured above, we see Mary and the baby Jesus, with the wise men offering their gifts on the left and the shepherds bowing in reverence on the right. This is like our nativity scenes today. But in the upper left, we see the wise men on horseback following the star. Beneath them, we see the angels appearing to the shepherds. On the upper right, we see the Holy Family’s flight to Egypt. In the lower left, we go back further, seeing a troubled Joseph being tempted by the devil to divorce his pregnant betrothed. And in the lower right, we see a midwife with Mary washing the new-born Child.

Now the early Christians were well-aware that the wise men came later than the shepherds. The Epiphany of the Wise Men was always celebrated 12 days after the Feast of the Nativity. But that the events surrounding the birth of Christ are depicted together has to do with their meaning. For example, in the icon above, notice that the baby Jesus is not shown as lying in a manger. Rather, He is lying on an altar. “Bethlehem” means “house of bread,” and He comes to us, presently, for our adoration and salvation, in the bread and wine of Holy Communion.

With the Renaissance, narrative painting became more “realistic,” depicting only one moment of the event. But the patron of this blog, Lucas Cranach, while painting with Renaissance perspective and realism, often employed the earlier approach to depicting Biblical narratives.

In his “Law and Gospel,” below, Cranach depicts on the left, Adam and Eve in the garden, Moses receiving the Law, the children of Israel dying from the serpents, plus the defining figure of a man tormented by death and the devil. Also Christ in Heaven. On the right half, we see John the Baptist pointing the sinner to Christ, who has come down to save us, on the Cross. We also see the empty tomb of His resurrection and His ascension. To underscore the meaning, Cranach also throws in a lamb and the crushed bodies of death and the devil, from the other side of the painting.

Our nativity scenes are in this tradition of Christian art.

Icon of the Nativity, from Sorofino, Russia.

“Law and Gospel” by Lucas Cranach the Elder – Herzogliches Museum Gotha, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=58440155