The conventional assumption is that slaveholders imposed Christianity on their African slaves and that separate black churches were the creation of white Christians who didn’t want black people in their congregations.

It turns out, those assumptions are wrong. In the course of her research into black entrepreneurship, Rachel Ferguson, the Director of the Center for Free Enterprise at Concordia University-Chicago, found that while the slaveholders were pushing a religion of pure law, the slaves were evangelizing each other with the liberating Gospel of Christ. And that the black church emerged from the members themselves as places where they could exercise leadership and build their culture apart from white interference.

I had assumed. . . that Black enslaved people became Christians through the efforts of slaveholders, but this is almost completely false. . . .Many southern planters were fairly unchurched Anglicans who knew just enough Bible to know that Christian slaves could make a compelling biblical case for their freedom based on various warnings to the Hebrews never to enslave one’s brothers and sisters. . . . Rather than being evangelized by their slaveholders, some of the enslaved converted at the tent meetings of evangelical revivalists, and they went on to evangelize one another when they returned to the plantation. As a result, the historical Black church is Baptist and Methodist, as these groups made up the majority of revivalists. (Pentecostalism doesn’t arise until the early 20th century and began as an interracial movement.)

Slaveholders were often furious, beating zealous new converts for praying with and preaching to one another. When white plantation missionaries came to preach to the enslaved, their every word was vetted by the masters, so that their preaching consisted of warnings against theft and disobedience with nary a word about Jesus Christ. . . In contrast, their own secret, nighttime gatherings of worship in “hush harbors” elevated their status as children of God, their joy in the belief that Christ died for them, and their aspiration for the same freedom that the God of Israel had provided to the ancient Hebrews. It was from these early meetings of the Black church that the tradition of the spirituals emerged, with their explicit celebration of spiritual freedom hiding the implicit longing for physical freedom.

Frederick Douglass’ account of his own conversion in his second autobiography is representative. Evangelized and discipled by his dear friend Uncle Lawson, he was ecstatic at the thought of salvation by Jesus and wanted nothing more than to spread the good news. He and Uncle Lawson prayed for and believed that he would someday be free. He was actively persecuted for his faith by his slaveholder, and he contrasted his own spiritual formation with the flaccid teaching that he overheard from his mistress’s pastor.

That account of Douglass, the escaped slave who became an eloquent abolitionist and champion of civil rights, can be found in his book My Bondage and My Freedom.

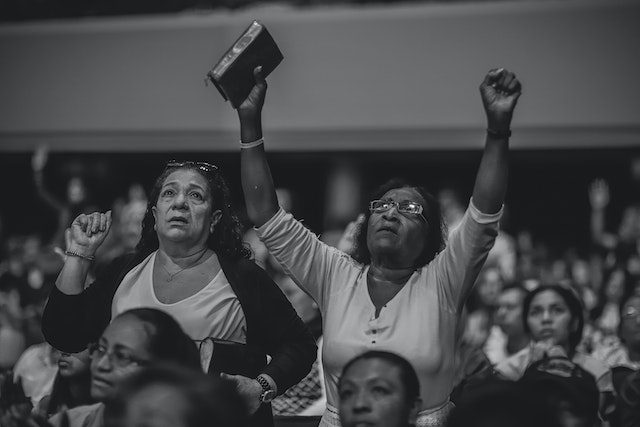

Blacks, unwelcome in white congregations, started their own churches, which became the “’cultural womb’ of Black America,” where leadership, community, and education were cultivated, and where new styles of music developed that would have a global influence.

To this day, Prof. Ferguson says, as we have posted here before, black Americans have the highest rate of church attendance, prayer, Bible reading, and belief in God of any demographic.

She notes too that black churches tend to be theologically and morally conservative. Black Baptists reject liberal theology, do not ordain women, and emphasize traditional sexual morality.

Black Missouri Synod Lutherans have been on the right side of theological issues even through the denomination’s flirtation with liberalism in the SEMINEX era. And in my experience they tend to be liturgically conservative as well.

Furthermore, Prof. Ferguson says that while they work for racial justice, “the secular, intersectional association of racial issues with unorthodox views on sex and gender [do] not align with the vast majority of Black churches.”

I wish I understood more how these churches, which I know to be theologically conservative, can bring themselves to work together politically with pro-abortion, pro-feminist, pro-LGBT+ white progressives. I suppose they tend to be politically liberal out of their own self-interest–though they used to favor the party of Lincoln, which is one reason Southern Democrats prevented them from voting–but as the Democrats abandon working class concerns in favor of middle class “life style” progressivism as Republicans take up those concerns, maybe another political realignment will emerge.

Photo by Luis Quintero: https://www.pexels.com/photo/grayscale-photography-of-people-worshiping-2774570/, via Pexels