At the contrarian website Unherd, I stumbled across a fascinating article that framed American politics in a way I had never thought of before. It’s by think tanker Michael Lind, entitled America’s new class war, with the explanatory deck, “In the US, both parties ignore a nation of communitarians.”

He observes that while the Democratic Party is fixated on identity politics and the Republican Party is fixated on opposing that, most Americans’ political concerns have to do with the economy, immigration, crime, schools, and the state of the nation as a whole.

He says that both parties are dominated by elitists, by well-off college grads who can afford to focus on theories rather than reality. Furthermore, both parties are in thrall to their wealthy donors, who influence the positions they take. He says that this is true even of the Democrats, who usually decry that sort of thing. Silicon Valley, for example, is full of progressive donors–such as Amazon’s Jeff Bezos, who owns the Washington Post–who have no use for unions in their own companies. Which Democrats, despite their old-school pro-union sympathies that they used to have, are fine with.

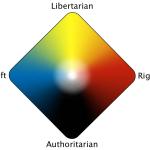

After much analysis of both sides that you really should read, Lind concludes that Republicans tend to be both socially conservative and economically conservative (being pro-business, pro-free market, pro-free trade). Whereas Democrats tend to be both socially progressive and economically progressive. But a substantial number of Americans, especially in the working class, are social conservatives but economic progressives! That is to say, they are communitarians! He concludes,

Taken together, then, we can see that affluent, college-educated voters and the donors in both parties are skewing American politics to the Left on social issues and to the Right on economics. This has left a substantial part of the American public unrepresented in our two-party system. Almost six years ago, the political scientist Lee Drutman, then my colleague at New America, the think tank I co-founded, used voting data to show that very few voters were consistent libertarians (socially conservative and economically libertarian), while 40% were in the socially-conservative, economically-progressive category. To put it another way, the libertarians have many donors but almost no voters, while the communitarians are not represented by either mainstream progressives or mainstream conservatives. (Drutman called this group “populist”, but communitarian is now a less pejorative term.)

I can see this. Working class Americans tend to be socially conservative, but they are fine if the government gives them money or social programs that benefit them. They are suspicious of big corporations and dislike the global capitalism that sends industries and jobs overseas. But they have no truck with identity politics, critical race theory, historical revisionism, transgenderism, and political correctness. They are pro-family, pro-church (even if they don’t attend much), and pro-American.

“Communitarian” means an emphasis on communities and on pursuing what is good for society, rather than just what is good for individuals. The term has strongly positive connotations among progressives, many of whom think that they are communitarian. Ironically, this seemingly benevolent ideology has found political expression in Donald Trump, a figure so reviled by elites from both sides that they do not realize the nature of what he stands for.

Lind’s framing reminds us that the desire to make America great again is a yearning to belong to a unified, strong, widespread community. Communities have a common history and a common heritage and valuing them highly is part of what creates a sense of community. (The word “common” derives from the same word as “community”; thus the interest in what we have “in common,” rather than how we are different.) Hence, patriotism and the much-derided term “nationalism” are intrinsically communitarian. And once-excluded groups–such as Native Americans, black Americans, and the various waves of immigrants–can also take their rightful place in the national community, as is evident in the simultaneous diversity and patriotism of our veterans’ associations.

As any sociologist or anthropologist will tell you, all communities have strong social norms. Individuals don’t go around doing whatever they want to do, choosing their own gender identity or experimenting with various lifestyles. Families are central to communities. So places with a strong sense of community will tend to be socially conservative.

And yet, focus on community can express itself in a desire for policies that benefit the community as a whole, to governments that do not simply “let people alone” but that offer positive help, and to economic policies that do not simply create wealth for individuals but that benefit the “common” worker.

Having said this, I’m not completely convinced that what Lind is seeing is communitarian in the full Wikipedia sense. Especially in the “illiberal” sense of being uninterested in individual liberty. Americans and in particular working-class Americans are fiercely attached to their liberties. That is part of being “American.”

Nor am I convinced that economic progressivism is a good approach to economics or that a big, activist government is a good thing.

Perhaps a better term for what Lind describes, the fusion of social conservatism and economic progressivism, is “Christian democracy,” in the sense of the European political parties of that name, before the “Christian” part began to wither away. (Actually, the Wikipedia article on “communitarianism” says that it is part of a series on “Christian democracy, which would suggest that the former term is a subset of the more comprehensive latter term.)

At any rate, Lind suggests why there is such a felt disconnect between much of the American public and both political parties. When the political parties are either purely conservative or purely progressive, someone who is socially conservative but economically progressive might vote for one or the other in different elections, while remaining dissatisfied with the choices.

Then again, Lind notes how the historic positions of both parties has been distorted, with the Democrats becoming less economically progressive and Republicans becoming more so. He is more critical of the increasingly elitist Democrats and is encouraged by the efforts of at least some politicians to make the Republicans the party of the working class. The question remains, though, whether the working class “communitarians” can prevail against the elites who control both parties.

Illustration from Niall Kennedy via Flickr, Creative Commons 2.0