Religion is pretty much a cultural universal. That is to say, no human culture is without one. So if Christianity disappears in the West, we can expect other religions to rush into the void. And those religions, say some observers, are likely to be a version of those that human cultures have turned to around the world and long before Christianity took hold. In other words, they will be “pagan” religions.

Other major religions today, such as Islam and Judaism, are also very different from paganism, and they have similar concerns with Christians about the prospect of its revival.

Rabbi Liel Leibovitz has written a fascinating article for the Jewish conservative magazine Commentary entitled The Return of Paganism with the deck, “The spiritual crisis afflicting contemporary America has ancient and enduring roots—and so does the cure.”

He cites statistics that show that in 1990, a survey uncovered about 8,000 Americans who said that they are “pagans.” In 2008, that number had increased to 340,000. In 2018, that number had increased to 1.5 million. This includes not only Wiccans (who tend to be feminists) but also the self-termed “Heathens” who follow the tenets of Norse mythology (who tend to be masculinists), as well as individual adherents who make up their own idiosyncratic pagan theology.

But Leibovitz is most concerned about what he sees as pagan traits that are permeating contemporary thought and culture. “To the pagans,” he says, “change is the only real constant.” He cites that pagan myths that describe the constant metamorphoses of the gods, which are continually changing their forms, assuming the appearance of humans or animals. This, in turn, leads to an emphasis on the changes in human life.

“The soul of paganism,” says Leibovitz is “the idea that no fixed system of belief or set of solid convictions ought to constrain us as we stumble our way through life.” He relates this to the relativism of today’s postmodern thought. And yet, there is more to both paganism and postmodernism.:

Still, change alone does not a belief system make, and pagans, despite differences galore, unite by providing similar answers to three seminal questions: what to do about strangers, how to think about nature, and how to please the gods.

What to do about strangers. The many forms taken by paganism are all tribal religions. Whereas the major world religions today are universal religions, generally with a transcendent deity that is sovereign over the whole world and is accessible to people of all cultures, pagan religions are generally tied to a specific community or nationality. Each tribe has its distinct gods who give the tribe and its customs a divine status. And the tribes and their gods are at war with each other.

Leibovitz relates this to today’s tribalism, specifically to intersectionality and identity politics:

The same spirit, alas, is alive and well among our newest pagans: For them, tribal warfare isn’t just a way of life—it’s a system of divination, with power and privilege waxing and waning to reveal who is pure and worthy and who evil and benighted.

Just like the Scandinavian pagans who offered precious gifts to appease the Askafroa, the spirit of the Ash Tree, a vengeful entity that demanded sacrifice lest it wreak havoc, many of today’s green activists seem much more intent on appeasing an angry god than solving a scientific conundrum.

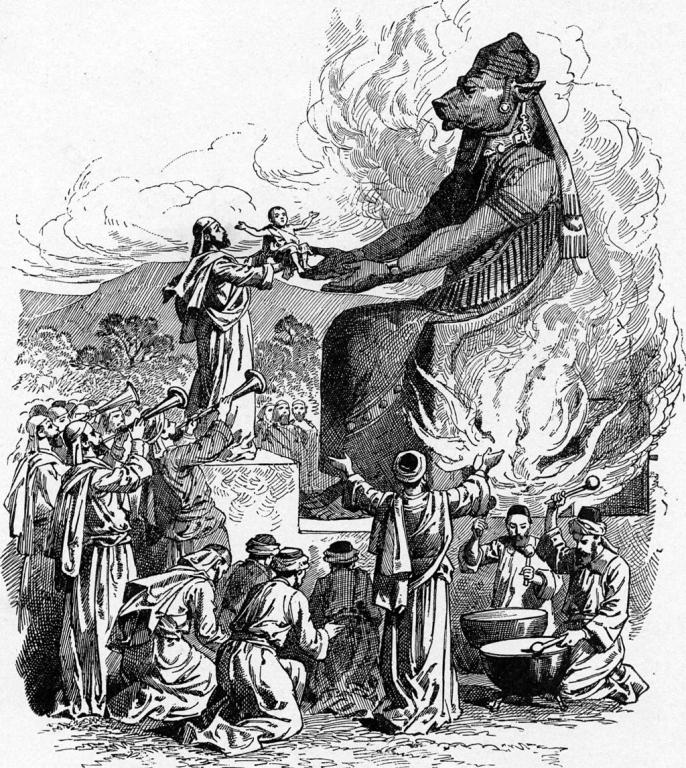

How to please the gods. The gods must be placated and appeased. But the gods have all the gold and silver they want, and animal sacrifices might seem too easy. So the ultimate offering human beings could give to a pagan deity would be their own children. Leibovitz says,

The pagans scanned the horizon for something truly precious and exquisite, something whose sacrifice would be an unmistakable sign of devotion. And, across time and across cultures, they alighted on exactly the same thing: kids.

At once the embodiment of innocence and the object of our deepest and most sincere emotions, children, the most vulnerable of mortals, were the ultimate offering to the gods—proof that the pagan believer was so certain in his belief that he would offer up his own offspring to show the gods the strength of his faith. . . .,

Child sacrifice, alas, is alive and well in America these days, too. We may not, like the Vikings, toss our young into wells as offerings to the heavens, but turn over every rock in our craggy contemporary political landscape and you’ll find some pagan policy offering up the well-being of children to the gods of virtue.

He cites the willingness of Americans to sacrifice their children’s well-being during the COVID lockdown by keeping them away from school and shut up in their homes, despite the mental and emotional consequences. Also the way the general public including some parents are subjecting children to mutilative surgery and sterilizing hormone treatments to signal their allegiance to the cultural god of transgenderism.

Strangely, he doesn’t mention the most overt example of today’s Molech worship, abortion. Parents are putting to death their own children to honor the god within, and the general public has convinced itself that doing so is righteous and pious.

Leibovitz has written a provocative article that is well worth reading in its entirety, but he is a rabbi, not a cultural anthropologist. What pagans most venerated about nature is its fertility, and they also venerated their own fertility. As I have commented elsewhere at this blog, fertility is most emphatically not venerated today. Rather, fertility is generally seen as an unfortunate side-effect of sex, to be medicated against, to the point of aborting what fertility produces.

And his thesis calls to mind what C. S. Lewis said on the topic:

It is hard to have patience with those Jererniahs, in Press or pulpit, who warn us that we are ” relapsing into Paganism”. It might be rather fun if we were. It would be pleasant to see some future Prime Minister trying to kill a large and lively milk-white bull in Westminster Hall. But we shan’t. What lurks behind such idle prophecies, if they are anything but careless language, is the false idea that the historical process allows mere reversal; that Europe can come out of Christianity “by the same door as in she went” and find herself back where she was. It is not what happens. A post-Christian man is not a Pagan; you might as well think that a married woman recovers her virginity by divorce. The post-Christian is cut off from the Christian past and therefore doubly from the Pagan past.

From De Descriptione Temporum [“of the Description of the Times”]. Inaugural Lecture upon accepting the Chair of Mediaeval and Renaissance Literature at Cambridge University, 1954. Published in C. S. Lewis, Selected Literary Essays.

Illustration: “Offering to Molech,” Foster Bible Pictures (1897) by Charles Foster, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons