As church affiliation plummets and American Christians fret about becoming a minority, we would do well to remember that Christians have always been a minority.

Consider texts like these:

“Enter by the narrow gate. For the gate is wide and the way is easy that leads to destruction, and those who enter by it are many.

For the gate is narrow and the way is hard that leads to life, and those who find it are few.” (Matthew 7:13-14)

For many are called, but few are chosen.” (Matthew 22:14)

And someone said to him, “Lord, will those who are saved be few?” And he said to them, “Strive to enter through the narrow door. For many, I tell you, will seek to enter and will not be able. (Luke 13:23-24)

A “little holy group”? But Luther was writing in the time of Christendom, when the whole civilization was Christian in one sense or another! But he was talking about individual congregations up against the temptations of the world, the flesh, and the devil. Even where Christians are the majority–and that’s still possible–we will feel small and beleaguered in this overwhelmingly sinful world, so that we must always cling to Christ who delivers us.

These thoughts are due to an essay I stumbled across in The European Conservative entitled The Metaphysics of Laissez-Faire Christianity and Pluralism by an anonymous student at Cambridge writing under the nom de plume of Erik Dahlbergh, the name of a 17th century Swedish Lutheran military engineer. He writes:

Christian religion is in a fundamental sense a minority religion. This is not to suggest that it does not tend towards, or that it cannot form, establishment. Rather, the point is that Christians reflexively assume that they will be in the minority. This means that the Christian does not depend, for the continuation of his faith, upon the assent of others. Jesus says, with myriad analogues:

If the world hate you, ye know that it hated me before it hated you. (John 15:18)

It is not my concern to discuss the veracity or the merits of Christianity. Of importance in this article is the fact that Christianity (and the Christian) presumes a state of alienation in the world. They expect to be aliens, and indeed if anything are concerned when they are not alienated (e.g. Luke 6:26). This is a more complicated position than it might first appear. What, after all, is the world? For the purposes of this article, I simply wish to point out that Christians do not depend upon their neighbours’ good wishes, let alone active support, to remain faithful. The Christian is in this sense, then, an ideal member of a ‘pluralistic’ society.

I want to suggest, in a reversal of this latter statement, that ‘pluralism’ as understood in modern parlance is a kind of post-Christian confusion. The Christian may not only be an ideal pluralistic citizen, but perhaps the ideal pluralistic citizen. On this view, pluralism would be the extension of a Christian consciousness to inhospitable forms of life. That is to say, it would be the transference of an expected social-psychological independence, not insensible with Christian people, to include non-Christian people. Pluralism falsely universalises the very unusual social-psychological qualities of Christian life.

Christians must always feel alienated from the world. That’s a genuine insight. We are to be in the world, but not of the world (John 17:14-16). We have vocations in the world, we love what God has created, and yet we dare not become “worldly.”

The faithful, says the author of the Book of Hebrews, “confessed that they were strangers and pilgrims on the earth” (Hebrews 11:13). This contrasts with the religious goal of coming to feel “at home” in the world. “For here we have no lasting city, but we seek the city that is to come” (Hebrews 13:14).

Dahlberg says that, as such, Christians make for the perfect citizens of a pluralistic society, such as our own.

He goes on to contrast the “liberal” citizen of a pluralist society, who stands on his own without needing the rest of the community, with the “natural” citizen who depends on the community.

“The natural person (which is to say, the normal person) craves affirmation from others,” he says. The Christian craves only affirmation from God. This independence makes “liberalism” (that is, a society built on individual freedom) and thus “pluralism” possible. But without Christianity, this liberalism doesn’t work, since people must affirm themselves from within, rather than from the transcendent God. Thus, they must choose their own values and “in-source” their minds, resulting in psychological incoherence. “Liberalism inherited a Christian psychology but, having jettisoned the Rock of Ages, built its political theory upon the sand.”

Thus, people who think of themselves as “liberal” must, in the absence of God, look to others for affirmation after all. Dahlbergh tosses off another insightful observation: “The LGBTQ ‘community’ is a project of reassurance, as the proliferation of rainbows is an attempt to coronate certain desires as values, by their affirming reflection all around.”

I’m not sure this is the complete picture. After all, when Luther describes the “little” company of Christians, he is not referring to individuals but to the congregation the individuals belong to, the community of saints. But still, Dahlbergh gives us much to think about.

Already in Europe, which Dahlbergh is referencing, Christians are a minority. American Christians may soon find themselves in a similar position. I have noticed in my travels that Europeans who still go to church and still hold to their faith tend to be very devoted. The church still lives, even as the culture dies.

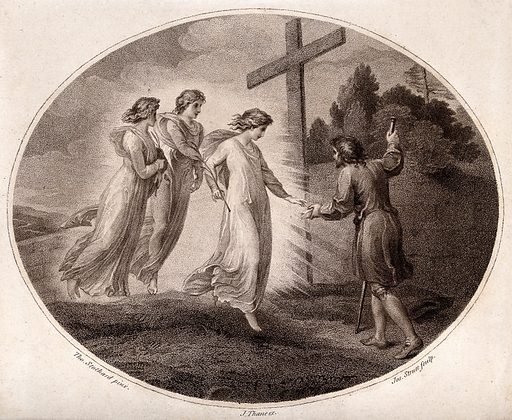

Illustration: “Three Angels Appear to Christian” from John Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress, by Joseph Strutt (1749–1802), Wellcome Collection, via Look and Learn History Picture Archive, Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0)