We’ve been blogging about the sharp drop-off in Christian belief and church attendance, as documented and explored in The Great Dechurching: Who’s Leaving, Why Are They Going, and What Will It Take to Bring Them Back? by Ryan Burge, Jim Davis, and Michael Graham. (See for example this post and this post.)

But Janine Giordano Drake, a history professor at Indiana University, offers some needed perspective on the topic. In her post at the Patheos blog Anxious Bench entitled Who Are Woke Christians and Haave We Seen Them Before?, she draws on the pioneering work of Henry Carroll, a Methodist minister who supervised the US Census of Religious Bodies in 1890 and 1906.

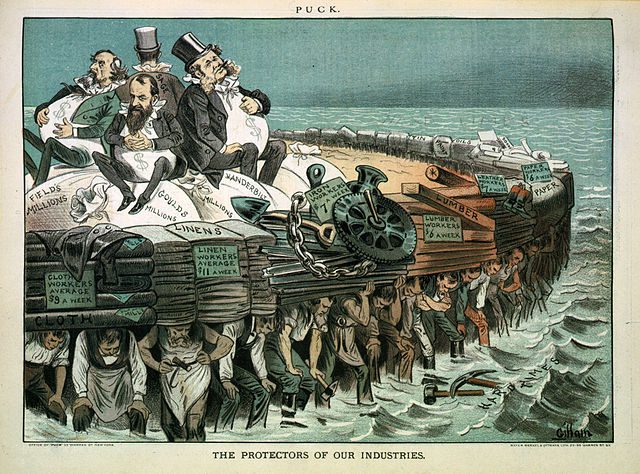

In 1890, the height of what Mark Twain called “the Gilded Age” of robber barons and industrialism, the extremely rich and the extremely poor, only 22.5% of the population was affiliated with religion of any kind. Put another way, nearly 78% of 19th century Americans did not go to church.

Today, according to the latest data I could find, 46% of Americans are affiliated with a church, which is indeed dramatically down from the 70% in 1992.

But even at this low point, the American population goes to church at more than twice the level it did in the late 19th century, a period Christians often idealize as the good old days.

This data poses another question worth pursuing: What happened over the course of 100 years, 1890 to 1990, to cause church membership to surge from 22.5% to 70%, a growth rate of more than 300%?

It would seem that the conventional wisdom is exactly wrong: The 20th century, despite its legacy of “modernism,” was NOT the age of secularism. Rather, the 20th century, in America at least, was an age of dramatic growth in religion!

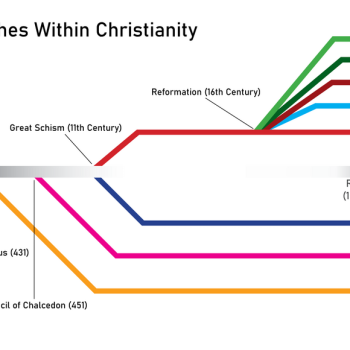

In 1890, according to Prof. Drake’s numbers from Carroll’s census, the church with the largest membership was by far the Roman Catholics, with 9.9% of the population, nearly all of whom were immigrants. The biggest Protestant group were the Methodists, still divided into a northern branch (3.5%) and a southern branch (1.9%), for a total of 5.4% of Americans. Then came the racially divided Baptists, with 2.1% in black churches and 2.0% being white Southern Baptists, for a total of 4.1%. Presbyterians amounted to 1.25% of the population. Episcopalians, .84%. And “small Protestant denominations,” which would doubtless include us Lutherans, had .83%. Jews were .26% of the population. Mormons were .21%.

Interestingly, the percentage of “atheists, skeptics, secularists, and infidels,” to use Carroll’s terminology was only 7.94%. That is almost exactly what it is today! Reportedly, about 4% of Americans are atheists and another 4% are agnostics. (“Infidels” is a category that is not currently recorded, though I think we should bring it back.)

These numbers would mean that just under 70% of Gilded Age Americans were “Nones,” as compared to 20-29% today. Nones but not atheists, people who may some personal spiritual beliefs but are not formally affiliated with any church or religion. Prof. Drake quotes Rev. Carroll as saying that many of them did consider themselves to be Christians, but were “unbelievers in the church.” That’s a very apt description still applicable today.

In fact, Prof. Drake says that the reasons so many 19th century Americans were not involved in a church were quite similar to the issues today.

She has written a book on the state of the church in the Gilded Age entitled The Gospel of Church: How Mainline Protestants Vilified Christian Socialism and Fractured the Labor Movement.

She describes herself as someone “enriched by the evangelical tradition, the Roman Catholic tradition, and the Lutheran tradition,” and who has also been “enriched by the Marxist and anti-racist traditions of activism and critical theory.” She describes herself as a “woke Christian” who says she understands the concerns of the critics of that category but would like to earn back their trust. Professionally, she is “a historian of socialism, Christian Socialism, and liberal Christianity.”

So that’s her angle, looking at the newly emergent “social gospel” that many Protestants were formulating, while perhaps missing the real economic and political needs of the burgeoning working class. Again, that also sounds like today.

Illustration: “The Protectors of Our Industries” by en:Puck (magazine); Mayer Merkel & Ottmann lith., N.Y.; Published by Keppler & Schwarzmann – US Library of Congress, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=40860170