Hobbes was writing just after the English Civil War (1642-1651), when the Puritans rebelled against the monarchy, defeated the king’s supporters in battle, and executed King Charles I.

(The Puritans and their allies, the even more radical Separatists, give us a Thanksgiving tie-in. The Mayflower “Pilgrims” settled in the New World because they were persecuted by King James, of Bible-translation fame, because they rejected the state church. Such tensions intensified under the next king, Charles I, whose policies were opposed by the Puritan-dominated Parliament, leading to the king trying to dissolve parliament, parliament refusing to be dissolved, and both sides raising armies. In the Americas, the descendants of the Pilgrims cheered the victorious rebels, accounting for the anti-monarchy strain in the colonies that was heightened after the British monarchy was restored and former rebels fled to the colonies to escape the new king, Charles II.)

Hobbes favored the royalists and lived in France with other royalist exiles, to the point of tutoring the Prince of Wales, who would become Charles II. But his 1651 book The Leviathan, though monarchist, displayed a religious position that was at best highly unorthodox and at worst coming close to atheism. The Anglican or Catholic royalists turned against him, but Hobbes found shelter and protection back home in the Puritan republic, Puritans and Separatists being much more tolerant of unorthodoxy and skepticism than Anglicans or Catholics.

Hobbes believed there were three–and only three–types of government, depending on who has the “sovereignty.” He writes, “When the representative [of sovereignty] is one man, then is the Commonwealth a monarchy; when an assembly of all that will come together, then it is a democracy, or popular Commonwealth; when an assembly of a part only, then it is called an aristocracy.”

He rather wittily remarked that those who disapprove of monarchy call it “tyranny”; those who disapprove of aristocracy call it “oligarchy”; and those who disapprove of democracy call it “anarchy.” But he goes on to consider which of these alternatives is best. That is, which is the most conducive to what Hobbes, who had just witnessed a bloody civil war, believed is the purpose of government: to “produce the peace and security of the people.”

He said that the problem with governments is that “private interests” often conflict with “public interests.”

Now in monarchy the private interest is the same with the public. The riches, power, and honour of a monarch arise only from the riches, strength, and reputation of his subjects. For no king can be rich, nor glorious, nor secure, whose subjects are either poor, or contemptible, or too weak through want, or dissension, to maintain a war against their enemies.

Whereas in an aristocracy, the interests of the few who govern may conflict with the public interest. And in a democracy, such conflicts are multiplied. (They didn’t have the word “lobbyist” in 1651, but Hobbes seems to have predicted them.)

Also, “a monarch receiveth counsel of whom, when, and where he pleaseth; and consequently may hear the opinion of men versed in the matter about which he deliberates, of what rank or quality soever, and as long before the time of action and with as much secrecy as he will.” Whereas a “sovereign assembly,” whether of the few or the many, takes advice from those who seem like experts but are often more expert “in the acquisition of wealth than of knowledge.” Also, when a group or a multitude is in charge, secrecy, which is often necessary in government, is impossible. (Hobbes thus predicts “leaks.”)

Also, “the resolutions of a monarch are subject to no other inconstancy than that of human nature; but in assemblies, besides that of nature, there ariseth an inconstancy from the number.” That is, we may have to worry about the weaknesses of human nature in a monarch, but there is even more human nature to go wrong in an aristocracy, and even more in a democracy.

Furthermore, “a monarch cannot disagree with himself, out of envy or interest; but an assembly may; and that to such a height as may produce a civil war.”

Thus, Hobbes believed a monarchy is more conducive to national unity than aristocracies or democracies. Dividing political power among either a group or the entire population will inevitably mean competing factions, internal divisions, and discord, “as may produce a civil war.”

Fair points! But Hobbes assumes the monarch will take advice from wise counselors. As we know from history, this often does not happen, as would-be counselors become little more than flatterers of the absolute ruler. Whereas government by a group or especially by the whole has the benefit of multiple minds addressing the problems. And of course a society will have multiple interests. They all need a voice so that they can be properly addressed and mediated. Furthermore, the individual who holds the position of monarch may or may not be qualified with the knowledge or virtues needed to govern justly or even to maintain the social order needed for peace and security.

Later thinkers in the “liberal” political tradition, such as the American founders, knew Hobbes and read his Leviathan, but addressed many of his concerns by a division of powers, checks and balances, individual rights, and the rule of law.

As for Hobbes’s three types of government, actual governments, ranging from tribal societies to modern constitutional republics, combine their elements so as to take advantage of the strengths of each of them, while checking their dangers: the tribal chief, the tribal elders, and the tribe itself; the Roman consul, the senate, and the assembly; the king, the parliament, the people who vote for their parliamentary representives; the president, the congress, the voters.

Hobbes was arguing for government as a “Leviathan,” a Hebrew word from the Bible denoting a huge sea monster defeated by God. He thought only a huge government with its tentacles in everything could provide peace and security.

Today, government has indeed become a “leviathan,” and we have learned through history and bitter experience how monstrous it can be.

Hobbes did not believe that individual freedom was a good thing, nor did he recognize individual rights. That is to say, he was writing before “liberalism.” He may have been right that letting someone else rule us would make for a more unified nation and allow for more peace and security (though that was hardly the legacy of one-person rule even in his own time, let alone the 20th and 21st centuries). But as Marxists on the left and Integralists on the right, and the significant percentage of Americans from both sides who believe that democracy is no longer viable, are willing to throw out liberty and self-government, we need to consider whether the alternatives are viable. And if an imperfect system might be better than any of its replacements.

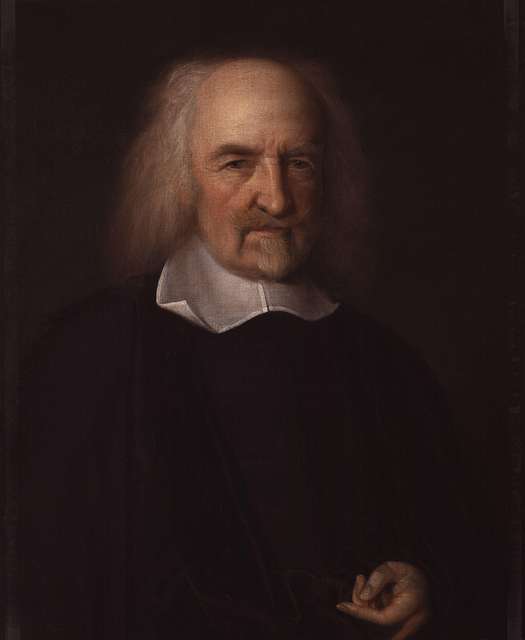

Illustration: Portrait of Thomas Hobbes (1670) by John Michael Wright, National Portrait Gallery London via Picryl, public domain