Halloween inaugurates a whole slew of holidays, one after the other in quick succession: Halloween, closely followed by Thanksgiving, closely followed by Christmas, closely followed by New Year’s.

It’s interesting that so many of our holidays are crowded into the cold days, when nature dies. That’s when we celebrate, rather than when one might expect, when the physical world flourishes with fertility and growth. We do have Easter, of course, in the Spring, but that is particularly tied to the new life that rises out of death–in Christ’s resurrection, heralded by the rebirth of nature, signifying the new life we have through Christ.

Religion looms behind holidays–a word that means “holy days”–even the ones that have become secularized or even paganized. Halloween was the eve before All Hallows, that is to say All Saints’ Day, a time to honor the blessed dead. (More death, but Christians can celebrate in the face of death.) What’s left of Halloween today resonates with the pagan fear of evil spirits and ghosts, but the sense of the supernatural and the uncanny–both of which which comes from religion–is preserved in people’s strange attraction for what is scary.

As for America’s national secular holidays, they either acquire a religious flavor–Thanksgiving requires a God to thank–or are celebrated in a religious way, with feasting (see that word’s etymology) as in the “festivals” of the church year that did not require fasting. So the main way we celebrate Labor Day is with a cookout. The same with Independence Day, though we add fireworks. New Year’s has a memory of the religious concern for new beginnings and is celebrated mainly with partying and staying up all night, the remnant of a vigil.

All of this came to mind when I came across an account of how a holiday was celebrated by someone resolved to purge Christianity from the culture as part of a new humanistic, rationalistic order.

After the success of the French Revolution, a ceremony was held in Notre Dame Cathedral–after the altar, the crosses, the Christian symbols, the art, and everything else that made its interior beautiful were removed–in which a woman who symbolized Reason was installed and crowned. Reason would be the new deity. The revolutionaries developed what they called a “Cult of Reason,” complete with holidays such as “Virtue Day,” “Talent Day,” and “Opinion Day.”

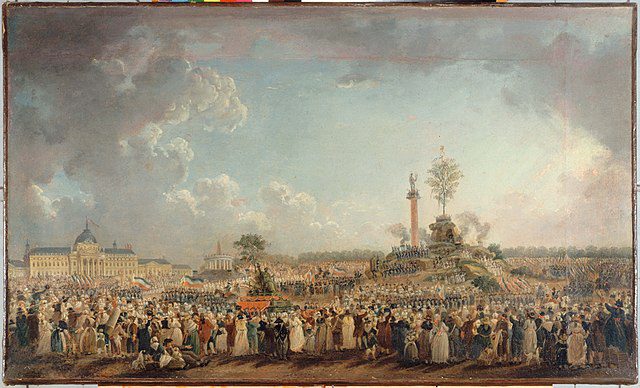

The Cult of Reason was atheistic, which pleased neither the people nor the Deists, who also rejected Christianity but held that reason demanded the existence of a Supreme Being. So when Robespierre came to power, he sent the advocates of the Cult of Reason to the guillotine. He replaced it with the Cult of the Supreme Being and planned a major nationwide festival in its honor to be held on June 8, 1794.

Here are his instructions for how the Festival of the Supreme Being was to be conducted:

At exactly five in the morning, a general recall shall be sounded in Paris.

This call shall invite every citizen, men and women alike, to immediately adorn their houses with the beloved colors of liberty, either by rehanging their flags, or by embellishing their houses with garlands of flowers and greenery.

They shall then go to the assembly areas of their respective sections to await the departure signal.

No men shall be armed, except for fourteen- to eighteen-year-old boys, who shall be armed with sabers and guns or pikes.

In each section, these boys shall form a square battalion marching twelve across, in the middle of which the banners and flags of the armed force of each section shall be placed, carried by those who are ordinarily entrusted with them.

Every male citizen and young boy shall hold an oak branch in his hand.

All female citizens, mothers and daughters, shall be dressed in the colors of liberty. Mothers shall hold bouquets of roses in their hands, and the young girls shall carry baskets filled with flowers.

Each section shall choose ten older men, ten mothers, ten girls from fifteen to twenty years of age, ten adolescents from fifteen to eighteen years of age, and ten male children below the age of eight to stand on the raised mountain in the Champ de la Reunion.

The ten mothers chosen by each section shall be in white and wear a tricolored sash from right to left.

The ten girls shall also be in white and shall wear the sash like the mothers. The girls shall have flowers braided into their hair. . . .

At exactly eight in the morning an artillery salvo, fired from the Pont Neuf, shall signal the time to proceed to the National Garden.

Male and female citizens shall leave from their respective sections in two columns, each six abreast. The men and boys shall be on the right, while the women, girls, and children below the age of eight will be to the left.

The square battalion of young boys shall be placed in the center between the two columns.

The sections shall be called upon to arrange themselves in such a way that the column of women is not longer than the column of men, in order to avoid disturbing the order which is necessary in a national festival. . . .

The National Convention shall arrive by way of the balcony of the Pavilion of Unity to the adjoining amphitheater.

They shall be preceded by a large body of musicians, who shall be located on each side of the steps to the entrance.

The president, speaking from the rostrum, shall explain to the people the reasons behind this solemn festival, and invite them to honor Nature’s Creator.

It goes on and on like this. So cold, so controlled, so regulated, so government-centered. Everybody forms up in tightly-organized battalions, marches through town, and listens to politicians.

In the former Soviet Union, Communist holidays were much like this.

Compare this kind of “festival” to the Christian holidays that were holy-days, as well as the secular celebrations modeled after them.

There is no sense of celebration, no letting go, no . . .fun. The word “feast,” as in the Feast of Christmas, connotes a special and abundant meal, but it ultimately derives from a word for “joy.” That’s what’s missing in secularist holidays and in secularism in general. It’s perhaps what we have to look forward to as Christianity fades from the culture. But joy is at the heart of Christian holy-days and Christianity in general.

Illustration: “Festival of the Supreme Being” by Pierre-Antoine Demachy (1794), via https://www.parismuseescollections.paris.fr/fr/musee-carnavalet/oeuvres/la-fete-de-l-etre-supreme-au-champ-de-mars, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=591304