In the midst of our current presidential campaign, with its turmoil and polarization,we would do well to review how the Founders of our nation wanted the president to be chosen. And, in fact, how the Constitution specifies that we should fill that office.

This involved no “running for office,” no campaigning, no advertising, no speeches, no debates, no primaries, no conventions, no get out the vote efforts, no ballot controversies. Rather, the people of each state would vote for Electors–individuals whom they trusted, but not political office holders–who would deliberate on what citizen would make the best president. They would then vote on their choices, and the results from all of the states would be counted by Congress. The person with the majority of the votes would be president. If no one had a majority, the House of Representatives would select someone from the top five.

The Electoral College was not a pro-forma ritual, as it is today. Rather, it was an active deliberative body whose charge was to find a good president. The people did not vote for a president, but for representatives to choose a president.

Here is the Constitutional requirement, from Article II, Section 1, clause 2 and 3:

Each State shall appoint, in such Manner as the Legislature thereof may direct, a Number of Electors, equal to the whole Number of Senators and Representatives to which the State may be entitled in the Congress: but no Senator or Representative, or Person holding an Office of Trust or Profit under the United States, shall be appointed an Elector.

The Electors shall meet in their respective States, and vote by Ballot for two Persons, of whom one at least shall not be an Inhabitant of the same State with themselves. And they shall make a List of all the Persons voted for, and of the Number of Votes for each; which List they shall sign and certify, and transmit sealed to the Seat of the Government of the United States, directed to the President of the Senate. The President of the Senate shall, in the Presence of the Senate and House of Representatives, open all the Certificates, and the Votes shall then be counted. The Person having the greatest Number of Votes shall be the President, if such Number be a Majority of the whole Number of Electors appointed; and if there be more than one who have such Majority, and have an equal Number of Votes, then the House of Representatives shall immediately chuse by Ballot one of them for President; and if no Person have a Majority, then from the five highest on the List the said House shall in like Manner chuse the President. But in chusing the President, the Votes shall be taken by States, the Representation from each State having one Vote; A quorum for this Purpose shall consist of a Member or Members from two thirds of the States, and a Majority of all the States shall be necessary to a Choice. In every Case, after the Choice of the President, the Person having the greatest Number of Votes of the Electors shall be the Vice President. But if there should remain two or more who have equal Votes, the Senate shall chuse from them by Ballot the Vice President.

[This process was adjusted with the Twelfth Amendment of 1804, which required Electors to cast separate votes for President and Vice-President.]

Why do it this way? Alexander Hamilton explains in The Federalist Papers, No. 68 (my bolds):

It was desirable that the sense of the people should operate in the choice of the person to whom so important a trust was to be confided. This end will be answered by committing the right of making it, not to any preestablished body, but to men chosen by the people for the special purpose, and at the particular conjuncture.

It was equally desirable, that the immediate election should be made by men most capable of analyzing the qualities adapted to the station, and acting under circumstances favorable to deliberation, and to a judicious combination of all the reasons and inducements which were proper to govern their choice. A small number of persons, selected by their fellow-citizens from the general mass, will be most likely to possess the information and discernment requisite to such complicated investigations.

It was also peculiarly desirable to afford as little opportunity as possible to tumult and disorder. This evil was not least to be dreaded in the election of a magistrate, who was to have so important an agency in the administration of the government as the President of the United States. But the precautions which have been so happily concerted in the system under consideration, promise an effectual security against this mischief. . . .T

Nothing was more to be desired than that every practicable obstacle should be opposed to cabal, intrigue, and corruption. These most deadly adversaries of republican government might naturally have been expected to make their approaches from more than one quarter, but chiefly from the desire in foreign powers to gain an improper ascendant in our councils. How could they better gratify this, than by raising a creature of their own to the chief magistracy of the Union? But the convention have guarded against all danger of this sort, with the most provident and judicious attention. . . .

Another and no less important desideratum was, that the Executive should be independent for his continuance in office on all but the people themselves. He might otherwise be tempted to sacrifice his duty to his complaisance for those whose favor was necessary to the duration of his official consequence. This advantage will also be secured, by making his re-election to depend on a special body of representatives, deputed by the society for the single purpose of making the important choice. . . .

The process of election affords a moral certainty, that the office of President will never fall to the lot of any man who is not in an eminent degree endowed with the requisite qualifications. Talents for low intrigue, and the little arts of popularity, may alone suffice to elevate a man to the first honors in a single State; but it will require other talents, and a different kind of merit, to establish him in the esteem and confidence of the whole Union, or of so considerable a portion of it as would be necessary to make him a successful candidate for the distinguished office of President of the United States. It will not be too strong to say, that there will be a constant probability of seeing the station filled by characters pre-eminent for ability and virtue.

That is to say, the Founders wanted to protect the office of the presidency from being taken over by demagogues, foreign agents, the unqualified, those with “talents for low intrigue and the little arts of popularity.” They wanted to establish a process that would be resistant “to cabal, intrigue, and corruption.”

That is, they wanted the office to be lifted above what we would describe as “politics.” And notice that in repudiating the Constitutional way, we have the “tumult and disorder” that the Founders were trying to avoid, as well as all of the dysfunctions that Hamilton feared.

By the 19th century, the political parties that Washington, Hamilton, and Madison had warned against emerged and each began running and campaigning for their own slates of Electors, which would develop into the kinds of elections for specific candidates that we have today.

The original way gave us presidents Washington, Adams, Jefferson, Madison, and Monroe. Once the presidency became a purely political office, the falling off was noticeable, giving us Martin Van Buren, William Henry Harrison, Millard Fillmore, etc., etc.

Some are saying we should abolish the Electoral College and elect our presidents directly by means of a popular vote. Perhaps a better option would be to abolish the popular vote and elect our presidents indirectly by the Electoral College as our Founders intended and as our Constitution prescribes.

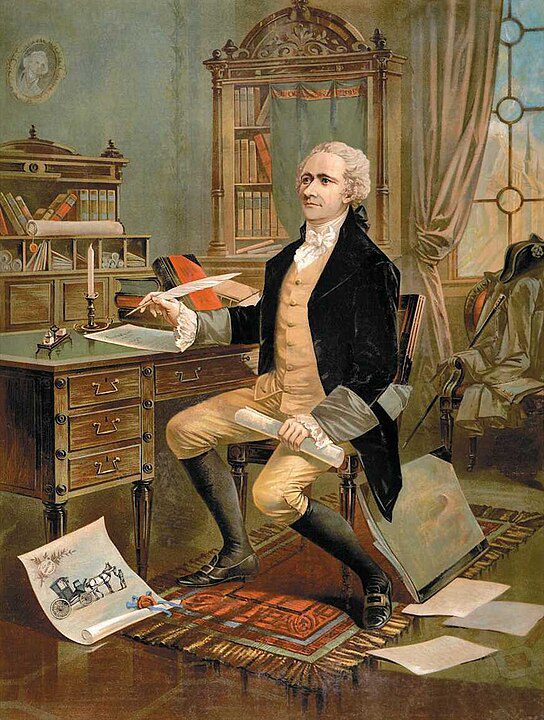

Illustration: Alexander Hamilton making the first draft of the Constitution for the United States 1787. An advertisement for the Hamilton Buggy Company (prior to 1892), https://www.forbes.com/sites/rhockett/2020/11/09/the-investamerica-planreconstruction-with-or-without-senate-help/?sh=1ff4369d78f2, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=126211276