It’s still Easter! The Easter season lasts for 50 days, until Pentecost, making it the second-longest season in the church year (next to Trinity, the long period between Pentecost and Advent). Those days of “Eastertide” commemorate the 40 days the risen Christ was on earth with His disciples, plus the ten days after His Ascension when the Holy Spirit descended on His church.

Just as we enjoy leftovers for several days after the Easter feast, here are some Easter devotions and reflections I came across online that I had to pass along. If you’ve come across other good Easter material–for example, insights you picked up from Holy Week services–tell us about it in the comments.

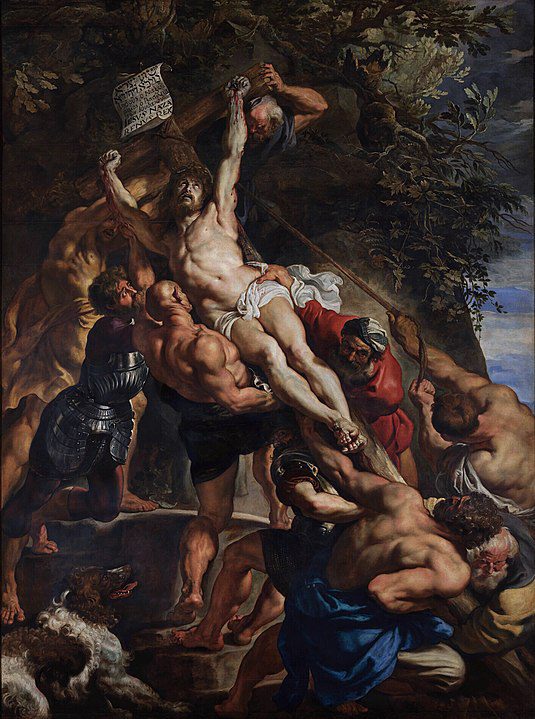

The Weight of Christ

Marc LiVecche begins his essay in Providence, Kavod! The Weight of Glory, with a discussion of Ruben’s painting The Elevation of the Cross (the illustration for today’s post, above). It shows nine hugely muscular men struggling and straining with all their might to lift up Jesus on the Cross. Jesus is too heavy! Probably because He is bearing the sins of the world. Including the sins of those muscle-bound brutes, plus a young soldier and some old men, representing the rest of us, who have been sinning so hard to put Him on the Cross.

LiVecche connects this artistic rendition of the weight of Christ to the Hebrew word kavod, which is translated “glory,” but which derives from the word for “weight.” This is the concept C. S. Lewis was driving at in his essay “The Weight of Glory.”

Now that people today have become disengaged from the glory of God and the glory that God promises for us in Heaven, LiVecche says, they lack weight. In other words, they lack substance. Postmodernism has characterized itself, in the words of Milan Kundera in his novel of that title, as cultivating “The Unbearable Lightness of Being.” Says LiVecche,

Relating to all this, sometime back, one of Providence’s original co-publishers, Robert Nicholson, lamented what he perceives as the hollowing out of human being. I’ve lost the notes and can’t reconstruct his argument entirely, but Robert was essentially mourning the loss of individual integrity, of ballast, of kavod. . . .Henri de Lubac called [this] the “waning of ontological density.” It’s a high-caloric phrase, but ontology is simply the study of what it means to be—or, to be human beings. Humanity’s spiritual predicament, in de Lubac’s assessment, is that we are hollowing ourselves out by abandoning a Christ-centered understanding of what it means to be a human being in the first place. Cutting ourselves off from this “ontological mooring” warns [Gil] Baillie, results in a “liberal self” that gluts itself on whatever pleases our own appetites, free from “the idea of a common good and any hierarchy of public goods.” We were not made for this kind of diet. Malnourished, our lives become increasingly disordered and dysfunctional and we suffer from an “unbearable lightness of being.”

By contrast, Christ carried out the will of God. By doing so, “his life could have gravity—a gravity so dense that nine well-muscled men could hardly lift it.”

God’s Silence

In his First Things piece God Gone Silent, Peter Leithart traces the imagery of sound and silence in the Bible. God creates the universe with his Word and His mighty voice is celebrated in the Psalms and throughout scripture. But with human sin comes death, darkness, and silence. “The wicked shall be silent in darkness” (1 Sam. 2:9; KJV). But the righteous too–and we ourselves–can be tormented by the silence of darkness and death.

But then “the loud and living God” enters the realm of silence. “The Savior who loosens the tongues of the speechless is dumb like a sheep before shearers. The God who is eternal Voice because he is eternal Life lies for three days quiet in the tomb. The eternal Word falls silent.”

God dwells in unapproachable light, but that’s no help to me if I’m groping in the dark, far from the light. God is the Word; every Christian believes that. But I can hardly hear his voice if I’m already tipping halfway into the silence. If he is going to be my Lord, he has to be Lord of light and dark, of life and death. If he’s going to rescue me, he’s got to come to me in the silence.

This is the purpose of incarnation: The Son took flesh to become Lord of death, so as to be Jesus, the Dark Lord. The Son enters the grave to become its master, to seize the keys of death and Hades. It’s not enough for him to have first place in creation. He must be the firstborn of the dead, so that in all things he might be preeminent. The Word dies to reign as Lord also of the silence.

The Poetry of Christ’s Death and Resurrection

The poetry editor of Modern Age, James Matthew Wilson, has written a piece called The Poetry of Death and Resurrection, in which he discusses poems about Easter and what it means.

He cites classic poems by such authors as Donne and Hopkins, modern poems by Eliot and Auden (also the less familiar Denis Devlin), and contemporary poems by Joseph Bottum and himself. He links to a poem by Bottum entitled Easter Morning, which concludes with this:

The parish bells begin their carols,

down through the trees like flourished prayer

the Easter call resounding. Time

reaches forward, hungry for winter,

and what will save my daughter when even

hope is caught in the ancient snare?

A cold fear waits—till all that had fallen,

all that was lost, rudely broken,

crossed in love, comes rising, rising,

on the breath of the new spring air.

Illustration: The Elevation of the Cross (1610-1611) by Peter Paul Rubens – Ophelia2, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=11688935