We have become so used to scammers–phony solicitations on the phone, sob stories and get rich schemes on emails, sexually-charged come-ons on social media–that we hardly pay attention to them any more. But some people get drawn in to these frauds, sometimes losing everything they have.

But who are these scammers? Criminals to be sure–con artists, fraudsters, and thieves. But in some cases, they are also trafficking victims, slave labor bought, sold, and abused. Law enforcement calls it “forced criminality.”

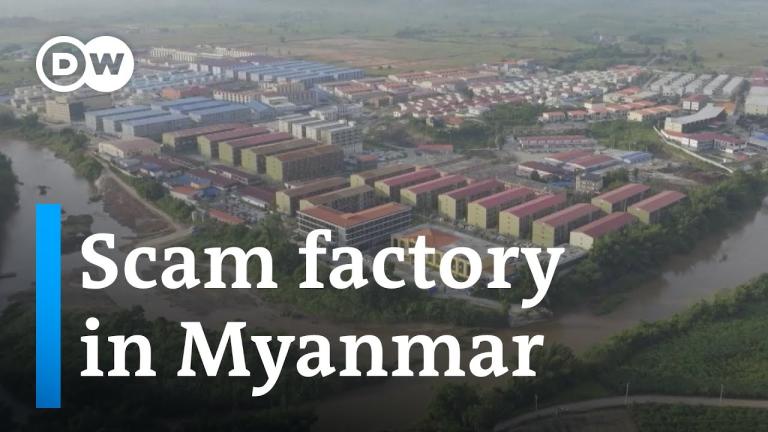

Scamming takes in tens of billions of dollars from around the world. Hundreds of thousands of people from Latin America, Africa, Europe, Asia, and the United States have been trafficked, sent to Myanmar (a.k.a. Burma) and Cambodia, where they are imprisoned in huge industrial compounds and put to work.

According to Solomon and Liang, these are operated mainly by Chinese gangs that at first were devoted to smuggling drugs, weapons, and people. “A few years ago, they discovered an even easier way to make money: They could simply trick people online into depositing cash directly into their bank accounts.”

They call the scam “pig butchering”– first fattening up the marks by gaining their trust, then butchering them by taking their money.

Scammers typically sit at desks manning laptops and mobile phones loaded with fake user profiles. Six former scammers interviewed by the Journal said the scam dens range widely in sophistication and propensity for abusing staff. But they all described a similar tiered labor system.

A screening team blasts out messages to hundreds of strangers a day, and passes those who reply to a different team, who then build relationships with the targets. Once the target agrees to put money on the table, they’re passed on to another, more technical team that handles transactions. Scammers are expected to “escalate” a certain number of victims each day.

If they don’t, they may be punished. The former scammers described punishments ranging from being beaten with sticks and shocked with cattle prods to being “baked”—forced to perform exercises like frog jumps in the sun in front of the others.

Solomon and Liang interviewed “Billy,” an IT expert from a poor family in Ethiopia who earned a master’s degree from a Chinese University. From there he accepted a job offer with a company only to be spirited to Myanmar, where he was sold several times to various traffickers who forced him to work the scams. “His captors made him assume the fake online alter ego of a rich Singaporean woman they called Alicia. He had to memorize a manual on how to seduce men online and manipulate them into pouring their money into bogus investments.”

The scam played out like this:

Day 1: Learn everything you can about your victim. Ask about their family, their job, where they live. Size up what they’re worth and if they’re vulnerable.

Day 2: Ask about their hobbies, and pretend you like the same things. Suggest to them that they enjoy shared interests together.

Day 3: Chat about past relationships. That night, confess that you’ve had a few drinks and tell the person that you like them.

Day 4: By now, they’re usually ready to start talking business.

The PDF contained detailed scripts telling the scammers exactly what words to use. It was like a choose-your-own-adventure novel, offering up options if the conversation took certain turns, or ran into obstacles like a suspicious wife or financial controls at the bank.

The scammers are trained and tested, Billy and Alfan said. Then they’re given about six mobile phones with WhatsApp and Telegram, and a laptop loaded with photos and videos of their alias, Alicia, as well as random pictures of things like food and pets and cars.

Wracked with guilt, Billy organized a strike. For that he was handcuffed and hung by his wrists for a week. Then he was tortured and beaten. Finally, his family sold their house so they could ransom him for $7,000, whereupon he was released. With the help of an anti-trafficking organization, he is back in Ethiopia, but he is ashamed to go back to his family, since he cost them their home, and he is still tormented for what he has done.

Photo: Thousands Trapped in Myanmar’s Cyber Slavery Racket via YouTube