“Even in churches that have stayed faithful to biblical orthodoxy,” observes Christian historian Thomas Kidd, “a spirit of pragmatism, consumerism, and individualism often prevails.”

He is reviewing Carl Trueman’s new book, Crisis of Confidence: Reclaiming the Historic Faith in a Culture Consumed with Individualism and Identity, an updated version of his 2012 publication The Creedal Imperative (2012). Trueman argues that Christians–he is particularly addressing evangelicals–need the creeds of the historic church in order to resist the pressures of today’s “expressive individualism.”

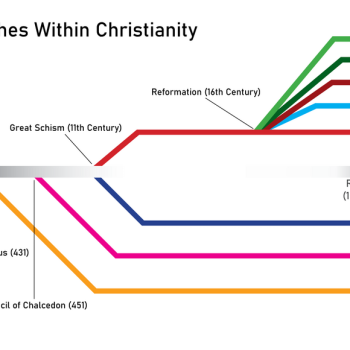

We Lutherans will say, yea, verily, to that. And yet, reciting the creeds is no assurance that a church will resist the mindsets that dominate our culture. Mainline liberal Protestants often recite the creeds in their worship services, but that has not prevented them from embracing the sexual revolution, transgenderism, and the other dysfunctions that Trueman chronicles in The Rise and Triumph of the Modern Self.

What struck me most about Kidd’s review, though, is his observation that not just liberal churches but even ostensibly conservative churches are infected with the modernist and postmodernist disease. From Religion & Liberty Online, The Historic Creeds vs. Passing Theological Fads:

Yet even in churches that have stayed faithful to biblical orthodoxy, a spirit of pragmatism, consumerism, and individualism often prevails. Doctrinal rigor is sometimes replaced by “your best life now” preaching (in megachurch pastor Joel Osteen’s phrase). This genre focuses on successful living more than historic doctrine. Church “members” come and go with blinding rapidity, often driven by factors such as which church has the most scintillating music or the most fun youth group. A church class on trinitarian doctrine might attract a few fogeys, but those on Christian-themed fitness or therapy will fill to overflowing.

Pragmatism does not just mean “being practical.” It means “being practical” takes the place of truth. As Wikipedia explains it (my bolds),

Pragmatism is a philosophical tradition that views language and thought as tools for prediction, problem solving, and action, rather than describing, representing, or mirroring reality. Pragmatists contend that most philosophical topics—such as the nature of knowledge, language, concepts, meaning, belief, and science—are best viewed in terms of their practical uses and successes.

This is not in accord with a Biblical view of reality; rather it is a modernist philosophy that has mutated into postmodernist relativism. And yet, such thinking is commonplace among conservative Christians. (As in, for example, the notion that emphasizing doctrine or Christian morality or traditional worship is not “practical” if we want to attract new members.)

Consumerism refers to a fixation on acquiring material goods, particularly as an index of status and identity. By extension, it is the mindset of giving the customers what they want, and, conversely, for individuals to reduce everything to a commodity for their consumption and to insist upon their customer satisfaction. This is tied into the postmodernist exaltation of the will and the appetite, in which “I like that” or “I don’t like that” takes the place of what is true, good, or beautiful.

In the church, this manifests itself in “church shopping” and the use of marketing schemes as a substitute for evangelism. Compare the “itching ears” syndrome warned against in Scripture: “For the time is coming when people will not endure sound teaching, but having itching ears they will accumulate for themselves teachers to suit their own passions” (2 Timothy 4:3).

Individualism is the exaltation of the self, which ties into the postmodernist notion that everyone has his or her own “truth,” which is a function of what one chooses. Says Wikipedia,

Individualists promote realizing one’s goals and desires, valuing independence and self-reliance, and advocating that the interests of the individual should gain precedence over the state or a social group, while opposing external interference upon one’s own interests by society or institutions such as the government.

Or the family. Or the church.

This mindset is evident among Christians whose faith is purely internal, who make up their own theology, have little need of other believers, reject any solidarity with the historic faith, and feel a commitment only to their own private church of which they are the only member.

Even those of us who do not take pragmatism, consumerism, or individualism to anti-Christian extremes, as some do, are influenced by these cultural winds of doctrine (Ephesians 4:14). Creeds and the historic confessions of faith can counter these ways of thinking and acting. Though theological progressives might recite the creeds but be little influenced by them, they might bring more conservative believers to their senses.

Says Kidd, drawing on Trueman, “a creed gives the church a focus of objective truth that does not change across time or cultures. The reality about God is not something we imagine or invent.” Also, “affirming truth stands in sharp contrast to expressive individualism, which asserts that one’s feelings create truth.” Furthermore, the creeds give us perspective:

Confessions consciously connect us to church history and remind us that Christianity is not primarily about me, my feelings, or my congregation, pastor, or denomination. Confessions de-center (but do not de-value) the trials of faith that individual Christians inevitably endure. Such trials (often related to “church hurt”) usually feature in “deconstructionist” testimonies on social media. One’s doubts about Christianity matter, but the fact that I have questions about Christianity or hurtful church experiences doesn’t change the massive heft of the Great Tradition of Christian belief and practice.

Kidd tells about how his own Southern Baptist congregation–a church body long associated with the slogan, “no creed but the Bible”–is now reciting the Nicene Creed. That’s progress! Or, rather, that’s regress!

Illustration via YouTube