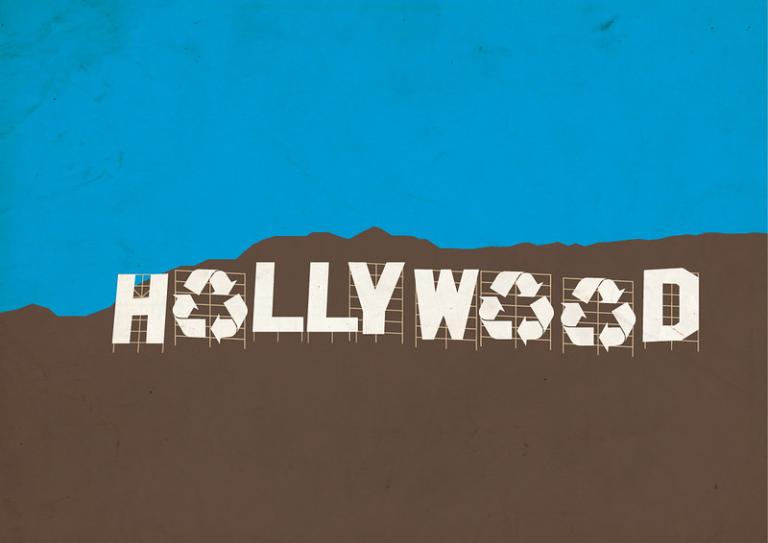

Have you noticed how many movies today are remakes of –almost always better–movies made years ago, or sequels of those old movies?

This lack of freshness, this repetition of formulas, this relentless looking back for material rather than coming up with something original seems to be a syndrome that plagues nearly all of the arts.

Ben Lawrence, writing in the UK Telegraph, vents about the reunion tour of the 1990s rock band Oasis, which apparently is taking up all of the oxygen in Great Britain. Lawrence concludes, in the words of the title of his article, We’re trapped in a neverending cycle of nostalgia – and it’s terrible for the arts. He writes,

This fuss around Oasis is part of a wider problem. We are trapped in a never-ending cycle of nostalgia, and it’s damaging our cultural life. Oasismania isn’t like Beatlemania, about which I wrote last week – it isn’t a capturing of the zeitgeist that offers brave new possibilities. It’s merely a way of harking back to past glories, apotheosising stuff that has been around for 30-odd years. In such a climate, how can new pop artists hope to break through? When was the last time you were daring enough to branch out and find a new artist on Spotify? Is it not just easier to take a trip down memory lane and relive your teenage years through the touch of a button?

I sought out the latest, cutting edge pop star only to learn that he is being praised for bringing back the 1970s.

The problem is not just with music and movies. Lawrence complains about the state of British Theatre, dominated by familiar old shows and plays based on old movies. (Check out the shows on Broadway.)

I see the same phenomenon in contemporary literature. (Browse Amazon’s bestsellers to see what I mean.) As for the visual arts, check out this overview of “contemporary art movements” and you will see styles that have been around for decades, in some cases for a hundred years.

And, says Lawrence, our amazingly cutting-edge technology is just making the problem worse: “Streaming may be a technical innovation, but it’s the enemy of creativity. Every online TV streamer, from Netflix to Disney+, allows us to wallow consistently in nostalgia; our favourite shows are now consistently at our fingertips and the past is always present.”

Lawrence concludes with this lament:

It feels as though our cultural habits are a sort of emotional cosplay. I understand: in difficult times we want to resurrect our past, and by listening to the music and watching the TV shows of our youth, we are, in some way, reconnecting with ourselves, something that you could argue is a result of having been locked down for two years. Yet this warm and fuzzy approach to culture has terrible financial implications. The Oasis tickets fiasco has proved that people are willing to part with large sums of money to relive their youths. They’re effectively saying, “What’s in the past is preferable” – and that’s nothing short of a tragedy.

But wait. This artistic stagnation is highly significant. It shows that our dysfunctional culture has arrived at a dead end. It has lost its creativity and its energy. Our pop culture and our high culture are exhausted. Lifeless.

That our artists are looking backwards may be a healthy impulse. Too bad, though, that they are only looking back to the 1970s. If they were to look farther back and bring what they learn from that into the present, they might jump start the arts once again.

Lawrence comments that the only arts he can find that is showing signs of life and creativity is classical music. “Oddly, with classical music and opera, the situation doesn’t feel as calamitous,” he writes. “These art forms, after all, have tended to dwell in the past, and their practitioners have become skilled in finding new ways to say old things.” He tells of hearing at the Berlin Philharmonic a piece that he has heard at least 30 times. “It felt fresh and exciting, as if I’d stumbled upon it for the first time,” he wrote. “It isn’t nostalgia driving the appeal of the past – it’s the realisation that our cultural history is endlessly surprising and can always be bent to our will.”

This is a sign that progressivism is ending. No longer do we hear that whatever is new is automatically better than what has gone before and that the past is something to discard. Not even political “progressives” are saying that things are getting better all the time and that we are evolving to ever greater heights. Their authors are writing dystopias. You will not find a utopian novel in all of Amazon.

Recognizing today’s intellectual, aesthetic, and spiritual dead ends can, ironically, be the herald of an advance for the arts. Of course, artists and the rest of us will need to abandon the stifling worldviews that have brought us to this place. If they do, if they adopt a worldview that is more friendly to truth, goodness, and beauty–I am thinking of Christianity–they might bring the arts back to life.

That would not mean just repeating the works of long ago. Good artists of every kind need to address the current contexts, but they can do so by means of classic styles and forms, which will doubtless enable greater insight into our current contexts than they are now.

NOTE: I am aware that there are doubtless artists of every kind–in music, literature, film, the visual arts, etc.–that are already doing truly creative, original, classical work that I’m not aware of. I am aware of some, actually, but feel free to mention others that you know of, so that the rest of us can know about them too and we can get this renaissance started.

Illustration: Hollywood – city of remakes, sequels, re-boots and what not by Viktor Hertz via Flickr, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0